With some fascination, I’ve been watching the burgeoning war between artists and AI art enthusiasts. One the one side, you have people who have invested years of practice to acquire difficult skills, and who now understandably see the development of technology as a real threat to their passion, livelihood, or even identity. On the other, you have people who thought they weren’t creative, now discovering they can have a lot of fun generating hundreds of images without having to spend a decade acquiring the aforementioned difficult skills.

In the middle of this conflict we find a fundamental question. It is one of many concerns around AI art (a set that also includes concerns about copyright, misuse, etc.), but one that seems particularly important as AI automates more and more spheres of human activity. It is this: What is the value of hard work?

To illustrate, a recent battle from the war.

It begins when Twitter mutual Gorm said he was trying to use the Midjourney AI to emulate the art of Tomm Moore (who notably made the animated movie The Secret of Kells). For whatever reason, his tweet escaped into the parts of Twitter that are populated by unresting spirits made of eternal fire that consume the souls of those who are not careful, and Gorm experienced being insulted by a lot of people, some of whom are presumably artists, some of whom are just unresting spirits made of eternal fire that consume the souls of those who are not careful.

Gorm stoically and admirably took the metaphorical beating, and engaged with a lot of the criticism. He says he talked with Tomm Moore himself, who intervened in the discussion to say he wasn’t happy about AI copying his style. But there’s one thing in particular that Gorm did that seems to have added fuel to the proverbial fire. When someone accused him of laziness — because he used AI instead of learning to draw — he just said, yeah, I’m lazy, and that’s a good thing. Before, lazy people couldn’t really explore their creativity. Now they can!

This did not calm down either the artists or the angry flame ghosts. Here’s a nice sample of the responses that are about hard work specifically:

It’s really upsetting to hear comments like that. And not just with AI art, but with anything. Hard work is the backbone of pride and quality. It’s always nice to see technology getting progressively better to make what we do manageable, but it’s not a substitute for dedication.

And that is all summed up as "I'm too lazy"

You don't get anywhere in any job without putting actual effort into it. If I didn't work hard on my art, I wouldn't get anywhere with my art. I wouldn't learn new techniques or get better at my art without working hard. If you're scared of working hard, art's not for you.

What’s interesting about calling someone lazy is that it seems to be a terminal insult. A moral failing. When someone accuses you of laziness, you can deny it, but you’re not supposed to just appropriate the insult. You’re supposed to agree with everyone else that hard work is a high virtue.

But is it?

There are pretty compelling reasons to say that laziness is actually fine, and that hard work for its own sake is bad. First is the biological fact that everyone hates effort by default. Of course, our bodies and minds don’t always enjoy the right things, but to a first approximation, our instinctive desires are a useful signal.

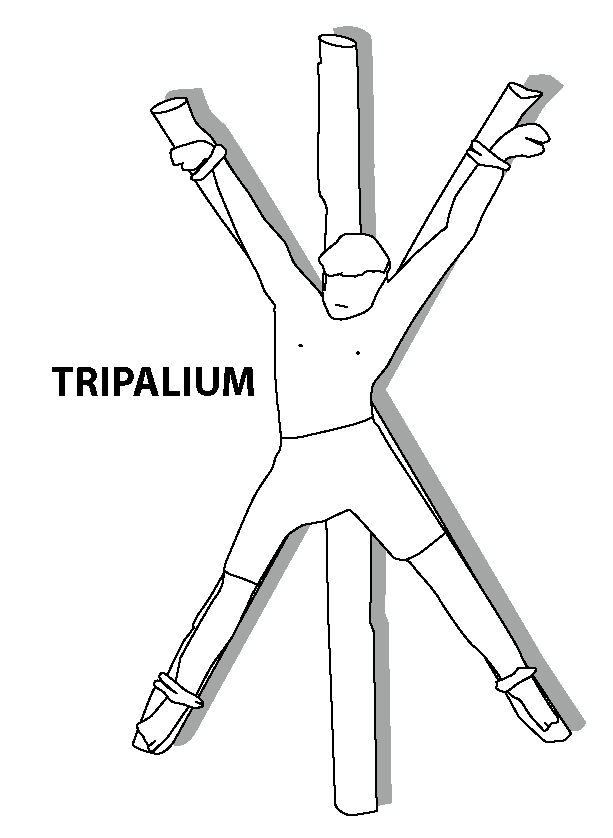

Second is the association of work with torture. The etymology of the English word “work” is a boring derivation from the Proto-Indo-European term for “doing,” but the main term for “work” in French (travail) and other Romance languages may come from a literal torture instrument, the tripalium.

In fact, we even have classic myths, like the story of Sisyphus, that depict pointless work as an instrument of torture. Sure, Albert Camus said that Sisyphus was happy because pushing his boulder forever, though pointless, gave meaning to his existence, but that’s an idea humanity only came up with in the 20th century after a lot of elaborate thinking. So for now, let’s focus on the surface level of the Sisyphus myth, the one that has been the standard interpretation for thousands of years: pushing boulders for no reason is bad.

Hard work done for a good reason, by contrast, easily seems virtuous. But that’s because of the good reason, not the work itself. We admire the people who have created art masterpieces, flourishing companies, or scientific discoveries, but while we recognize the hard work that went into them, that’s not what we truly value. If these people had worked exactly as hard as they did and yet failed to produce the final output, the harsh truth is that we wouldn’t admire them as much.

Besides, we may even have a tendency to admire lazy geniuses more: everyone likes stories of an art or math prodigy who seems to effortlessly produce great stuff.

Lastly, because everybody hates hard work, a lot of the hard work we do actually has the purpose of reducing future work. A substantial fraction of technological progress could be summarized as trying to make our lives easier. Dishwashers are great, because doing the dishes sucks. It seems silly to claim that using a dishwasher is dishonorable. In this way, we can even view laziness as a virtue: it is what compels us to find more efficient, faster, easier means to do things.

And the result is that most people today actually don’t have to toil as much as their ancestors did. Most of us have significant leisure time, which we can spend enjoying art or whatever else we like.

So, from this point of view, AI art enthusiasts are right, and artists are wrong. To the extent that AI reduces the need to spend years learning to draw, we’re collectively better off for it. It certainly does suck for the people who already spent that time, and they deserve sympathy, but we’re not going back to horse-drawn vehicles just because the transition harmed horse professionals.

Still… it seems somehow wrong to praise someone for their laziness. Despite the reasoning above, it really feels like I’m not supposed to do that!

Why might that be? It’s probably a direct consequence of how culture evolves.

As we saw, hard work is good when it leads to high quality output, like “enough food not to starve” or “aesthetically pleasing video game.” The relationship between hard work and high quality output isn’t straightforward, but it at least seems to have the following properties:

For many types of high quality output, hard work is a prerequisite (e.g., building a skyscraper definitely seems hard along many dimensions)

More generally, high quality output and hard work seem to be positively correlated even if they’re not directly proportional (over time, a hardworking programmer will probably produce more good code than a lazy one)

Hard work is easier to feel, notice, and measure than high quality output (this is especially true while the output isn’t finished; it’s easier to count work hours and notice the tiredness than evaluate the quality of the partially-made skyscraper or code)

These properties suggest that hard work is an attractive proxy for high quality output. Something that’s more directly measurable, and is reasonably correlated.

The problem is, evolution loooooves proxies. It loves everything that can maximize reproduction, and doesn’t give a fuck about anything else. It will happily maximize an awful behavior like eating your mate after sex if it’s somehow a good proxy for reproduction.

The following hypothesis therefore seems highly plausible. Let’s simplify and say that laziness is a meme your brain can be “infected” with or not. People with this meme are less likely to take care of their health and succeed at their work, finances, and relationships. As a result, they are less likely to pair and have children, or, if they do, they are less likely to raise these children to be successful in turn (especially since children acquire many of their memes from their parents). Lazy people are also less likely to develop a good reputation and inspire other people to become lazy as well. As a result, the meme of laziness doesn’t spread.

At the scale of an entire society, a similar scenario plays out. Cultures in which being lazy is seen as a virtue are less likely to achieve high economic and technological development. They are therefore vulnerable to influence or conquest from cultures that value hard work instead. As a result, these cultures die out, and the meme of laziness with them.

We are the descendants of generations of mothers telling their kids, “Look how successful your uncle got thanks to his hard work! When you grow up you can work hard just like him.” And so praising laziness seems to go directly against this enormous body of accumulated wisdom.

In this view, then, the anti-AI artists are correct in a sense: hard work is good for society, and it’s fine to criticize people who explicitly praise laziness. But that rings hollow once we realize that hard work is just a proxy. It doesn’t sound great to just pretend that hard work is virtuous.

The remaining view is that there are genuine reasons to value hard work for its own sake. Why might it be good for Sisyphus to push his boulder, even if we know it achieves no purpose whatsoever?

One possibility is that it’s an opportunity for personal development. Even if what you’re working on doesn’t get you any useful output, you’ll learn a thing or two about yourself or the craft, and that’s good. Sisyphus might be a better man — or, well, a better damned soul — after an eternity or two pushing his rock.

To which I say, sure, but learning is just a different kind of output. It’s a delayed reward: working hard on your crappy drawings won’t make you an artist now, but you expect it to be useful at some point in the future. This doesn’t seem very much done for its own sake. I guess we could say that the distance between the proxy and the valuable thing is shorter in this case, but still, I’m not convinced that it’s a reason to care about hard work per se.

A second possibility is Camus’s existentialist interpretation, which as far as I can remember goes roughly like this: existence is absurd and meaningless, but we can rebel against the absurdity by accepting it. Sisyphus is probably happy the the extent that he has accepted his eternal toil as pointless. That’s as much meaning as one can ever hope for.

But if existence is absurd and we can find meaning wherever, I don’t see why hard work should be a better source of it than laziness. Similarly, though it can certainly be fun to learn how to draw, many other things are fun, including using AI art. If almost everything is an equally good potential source of meaning or fun, then hard work is superior only insofar as it’s a proxy for other things we care about, as we discussed before.

We are left with a third and last possibility: that hard work is virtuous precisely because it is hard, and consequently, rarely done.

Here you will hopefully forgive me for drawing an analogy with bitcoin. Why is bitcoin considered valuable by many? Because it rests on a complicated system that creates an artificial but real scarcity, thanks a lot of otherwise pointless (or even environmentally harmful) cryptographic calculations. In other words, hard work — though fortunately work that is performed by computers, not people. The immense computational effort required to transact in bitcoin is what makes the network secure, because it would be ridiculously expensive to create a fraudulent transaction without anyone else noticing.

Bitcoin is the digital analog to gold. Why is gold considered valuable by many? Because it’s rare and difficult to find in nature. There are inherent chemical properties to gold that are useful, like its yellow color, but those matter far less than its scarcity.

This line of reasoning applies to many, many things. Why is real estate considered valuable to the point of being an investment? Because owning land and houses is useful, sure, but also because real estate is scarce and we don’t build enough houses. Why are paintings by Leonardo da Vinci considered valuable? Because they’re rare, and it seems highly improbable that we’re ever going to get new ones.

So, why is hard work considered valuable by many? Because most people prefer to be lazy than to work hard, and so hard work is rare. If you do work hard, then you are unusual. Since hard work is correlated with high quality outputs, then you are unusual in a probably positive way. People might notice, and grant you some kind of high status.

The status is not wholly independent from the actual outputs of hard work, just like the value of gold does come to some extent from its properties, and the value of real estate comes to some extent from what we can do with the land. But it is a real, and distinct, component of the value. Useless Rube Goldberg machines aren’t as high status as useful machines, but we do like them anyway: they’re interesting because they’re complicated and difficult to build.

Status is a weird creature. It’s unclear to what extent we should care about it, but in practice we definitely care a lot. In a world where AI automates a lot of stuff, it will surely become even more important. So that’s a legitimate reason, if not a fully satisfactory one, to care about hard work: it’s a way to gain the status we all crave.

So who’s right? “Lazy” AI artists, or “hard working” human artists?

Sorry, I’m not going to actually pick a camp. My actual answer is a boring nuanced one:

You can definitely work hard at using AI, tweaking prompts, etc., so AI art isn’t inherently lazy (though it can be!)

You can also be a super lazy artist, so human art isn’t inherently hard work (though it can be!)

People who care about the hard work of learning to draw because they have done it obviously have investment bias, which doesn’t mean they’re either right or wrong

Hard work has some value, but the extent to which that value is real (not a proxy) and material (not just status) is debatable.

Beauty and art are dazzlingly multifactorial: they reflect literally everything that we value, including hard work and laziness. Some art is beautiful/good because it involved hard work; some is even though it didn’t; some is because it didn’t.

And so, in this poll:

… the true answer is “all of the above, and a million other things besides.”

There are two conflated meanings of laziness here: taking shortcuts to save time, and not using one’s time to work. Hard work as a converse of the first represents the waste of human potential (barring some of the side benefits you mentioned). Hard work as a converse of the second can be a virtue *even if* it is only a proxy for things we actually care about. Time not used creating art, improving one’s own or others’ condition, etc, represents a massive opportunity cost. The virtue of hard work is to recognize people who use the efficiency gains of the shortcuts to maximize their potential and create greater total output, rather than the same output for less work.

I really like your analysis.

For me personally there's always been this unspoken ambition (see, I own it now) to be lazy AND successful. It feels like the pinnacle of existence to me, for some reason. Succeeding by putting in as little effort as possible feels like moving with grace through the terrain, finding the middle path instead of using brute force or expecting to be carried by someone else...