More People Means More Good

AWM #71: Misanthropy is deeply wrong; we ultimately need more of us 👶

There’s a certain kind of argument that goes like this: “Humans are responsible for $BAD_THING. Therefore the way to solve $BAD_THING is to have fewer humans, or no humans at all.”

(Substitute the $BAD_THING variable with whatever problem your society currently has. A popular one is climate change.)

Let’s call this the Misanthropic Argument. The Misanthropic Argument is a bad argument. Actually, “bad” is too mild. It’s an evil argument. Accepting it — and following it to its logical conclusions — is one of the worst things you can possibly think.

This strong statement shouldn’t surprise anyone who has read last week’s essay, in which I argued that the worst evil is emptiness, or non-existence. Even a painful existence has more value than non-existence, just like liquid nitrogen, even though it’s absurdly cold by our standards, has more warmth than the absolute zero.

There are many reasons for this. One that I didn’t elaborate on last week is that values don’t exist in the abstract: they are derived from conscious thought. If there are few or no humans, then there are simply fewer or no conscious observers to assign value to things, and as a result the world as a whole is less valuable.1 The beautiful, natural, humanless world you imagine seems beautiful and good because you exist to imagine it. If nobody were around to experience it, it wouldn’t be beautiful. For all we now, there’s a planet out there full of non-conscious plant or microbial life, and as long as nobody finds it (or evolves on it), then it doesn’t produce an iota of value.

The Misanthropic Argument has several real-world incarnations. The best-known one may be Malthusianism: the idea, laid down by Thomas Malthus at the end of the 18th century, that exponential population growth would deplete a finite amount of resources and lead to famine and catastrophe. This line of thinking is still widespread, even though pretty much all of its predictions have been wrong. Despite the projections pointing to a world population that will stabilize or decrease, overpopulation is still a common talking point. Combined with worry about climate change and other environmental concerns, this has spawned ideas such as degrowth — which says we should overhaul society to gradually reduce the size of the economy and human population.

Sometimes the Misanthropic Argument takes the form of deep ecology, which goes flatly against what I described above: it says that nature has value regardless of humans. It’s not necessarily bad to think in this way — i.e. to view humans as only a part of the biosphere as opposed to superior beings who sit atop the rest — but it’s all too easy to go from there to considering humans as a parasitic life form that is slowly destroying Earth.

The most extreme from of the Misanthropic Argument might be ecofascism. Ecofascism advocates for totalitarian government and possibly even stuff like genocide to control human population in favor of the natural environment. As you can imagine, I am not a fan.

Ecological concerns dominate the field of misanthropy, but we can imagine other instantiations of $BAD_THING. Someone could argue, for example, that humans cannot exist without exploiting other humans, which causes suffering, and therefore there should be no humans.

Okay. Suppose you are an evil person and accept the validity of the Misanthropic Argument. How can you reduce or eliminate humanity? Except for the most extreme ecofascists, pretty much everyone agrees that murder and genocide are bad. Dying from non-human causes is also not great, even though a few evil people did rejoice when covid was supposedly “getting rid of the human virus.” If you can’t increase deaths, then you’ll have to reduce births. Thus we get the philosophy of antinatalism.

Antinatalism asserts that making babies is morally wrong. It’s a complex set of ideas, not all of which are directly related to the Misanthropic Argument. (For instance, one version of antinatalism is based on the fact that new people can’t consent to being brought into the world.) But the outcome is always fewer humans. More non-existence. More evil.

But enough about evil. Let’s talk about good.

The opposite of the Misanthropic Argument is the Philanthropic Argument. It can be stated like this:

Humans are responsible for $GOOD_THING. We would like more $GOOD_THING to exist. Therefore we should have more humans.

(Substitute the $GOOD_THING variable with whatever desirable outcome you would like to see more of. Popular examples include love, friendship, art, comfort, technology, fun, and wealth.)

If you accept the validity of the Philanthropic Argument, then it’s in your interest that there be more humans. How do we make more humans? One option is to extend the lives of existing people. This is the philanthropic goal of medicine as well as more exotic projects like longevity tech and cryonics. The other option is to make more babies. In other words, pronatalism (or natalism): the opposite force to antinatalism.

By default, the vast majority of people are pronatalist in a weak sense, due to basic evolutionary forces. Natural selection favors genes that lead to higher survival and reproduction. Cultural evolution favors ideas that lead to higher transmission of themselves (and the best way to transmit an idea like religion, language, or “family values” is to give it to your kids). Antinatalism is an evolutionary dead end.

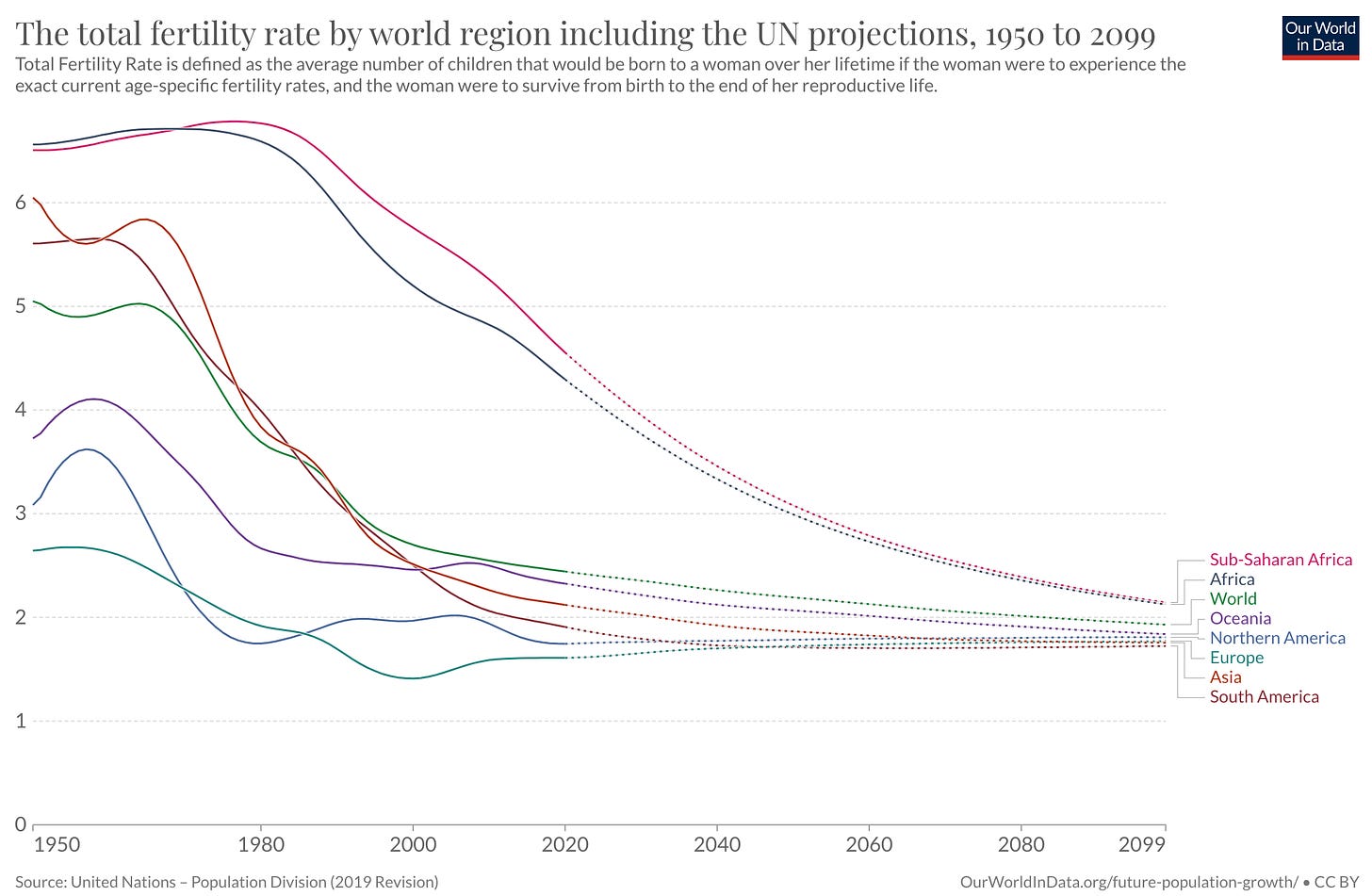

But evolution, whether biological or cultural, operates on relatively long timescales. In the short term, we’re not making a whole lot of babies anymore. Fertility in rich countries is almost universally below the replacement rate of 2.1 children per woman. This means that their populations are decreasing, unless they compensate with immigration from places with high fertility. But those places are expected to become like the rich countries as they develop their economy. In the long run, fertility will remain low, and world population will stabilize or even decrease.

So it makes sense to describe a strong version of pronatalism that goes beyond a vague sense that families are good and that babies are cute. This form of pronatalism says that we should actively encourage people, perhaps with governmental policy, to start families. The means could include financial support, dealing with the obstacles in their way, or cultural change.

Pronatalism is somewhat difficult to discuss, because it inevitably touches upon deeply held values, not the least of which is the role of women in society. Natalist policies in countries like Hungary are often criticized. They also don’t usually work very well in terms of raising fertility rates.

But there’s no reason that we can’t have a common-sense pronatalist philosophy that most of us could agree with. It would start by explicitly saying that having children is a personal choice and that no one should be pressured to start a family against their wishes. It would suggest a bunch of non-coercive ways to encourage people to have kids. It would debunk the idea that climate change or war or covid or economic inequalities make this world unfit to bring children into. It would explain, crucially, why we need and should be optimistic about this.

More people means more good. There are, of course, challenges to dealing with large populations, such as resource management and coordination. And some people are individually not so good, even though even the worst of them still carry nuggets of goodness inside them. But despite those caveats, the rewards to maximizing the number of people are great: more art, more new ideas, more fulfilling relationships, more economic growth, and, fundamentally, more conscious beings that can enjoy an awareness of the universe.

All of this is threatened by the people who accept the Misanthropic Argument. So please don’t let your fear of $BAD_THING trick you into agreeing with them. We need to maximize $GOOD_THING, and the only way to do that is by creating more of us.

The argument takes a slightly different form if we consider that some animals, or, speculatively, robots or aliens, have conscious experiences too. But it’s still valid, because the number of conscious observers matters, and so does their level of consciousness. It’s highly unlikely that reducing human population would raise the sum of all consciousness in the world.

Here are two roads against anti-natalism and misanthropic beliefs: hyper-natalism (EA's rationalization of using babies to solve problem for its sake) and selective natalism (eugenics through promoting smart baby births). The former leads to an naïve idealistic foreign aid, even if the country or the charities involved are corrupt (telescopic philanthropy) or inept at upholding principles of freedom (tabula rasa and eurocentrism). The latter is classic tribalist reactionary thought in the sphere of "human biodiversity", which has some tough moral roads with excessive ethnic self-interest.

This leads to a paired indicators of: maximize intellectual prosperity, minimize cultural conflicts. *looks at Singapore*