We used to have a plethora of physical office tools. Calculators, printers, fax machines, typewriters, cameras. Pens, scissors, tape, paperclips, staplers. Calendars, dictionaries, bulletin boards, organizers. Now all of this is more or less obsolete. They have been turned into electronic versions of themselves, and bundled into the same one tool: the computer, whether desktop- or pocket-size.

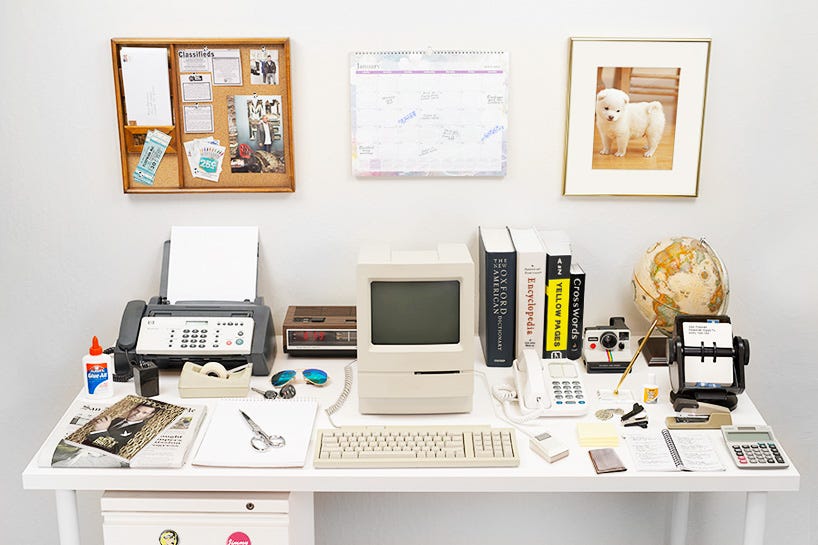

There’s a pretty cool video that wonderfully illustrates the evolution of the computer desk from 1980 to 2014. It starts like this:

and ends with this:

In terms of physical footprint, there’s no other way to say it: that’s a total collapse.

The benefits of this bundling are obvious. Carrying a smartphone is far more convenient than carrying all of the devices and tools and media above. It’s cheaper overall; it uses fewer resources. It also makes it easier to develop further products: you can solve a problem with a new app without having to deal with the complications of making physical stuff.

Less obvious, perhaps, are the disadvantages.

The first is vulnerability. By centralizing many functions of daily life into a single tool, you’re at risk of being severely hindered if you lose that one tool. This is especially true now that our phones also play the role of key to log into so many online accounts, thanks to two-factor identification.

The second disadvantage is distraction. I use my phone both for adjusting the volume of the music in the house and for scrolling Twitter. If I’m doing some focussed non-phone thing, like reading a book, and I want to reduce the volume of the music, then I need to get on my phone. There’s a significant chance, every time, that I’ll be attracted to Twitter and quit reading my book. Worse, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to just leave my phone in another room to avoid distraction — then I can’t adjust the music at all!

The third disadvantage is the loss of sensory pleasure. When you do everything through a touchscreen, there is no variety in physical sensations, no textures, no shapes, no sounds. Someone once said that modern movies are no longer realistic, because if they were, the characters would just be spending their time in front of a computer or phone all the time, and that’d be boring. Yet that’s what we do, at least the “knowledge workers” among us: we move pixels around on screens all day, instead of doing embodied, physical tasks.

In all cases there exist workarounds. But it takes some willpower to implement them. In practice, most of us are vulnerable to losing our devices; we’re constantly distracted; and we’re less physically stimulated than we could otherwise be. None of that outweighs the benefits — but they’re real concerns.

Sometimes it’s worth going against the trend. For example, in listening to music, I have partly reverted to analog technology. I now have two parallel sound systems: a digital one, for the TV and for when I want to immediately access something specific on Spotify; and an analog one that can play vinyl records and good old-fashioned radio waves. That’s what I use the most, nowadays. It feels great to just press a physical button with tactile feedback and hear the radio right away, without having to mess around with my phone and its flat interface that is also a dark portal to Twitter.

But that’s just a tiny quirk of my home. In general, the trend is inevitable.

The opposition between these two poles — let’s call them tool standardization and tool diversity — is just an instance of the eternal opposition between monocultures and cultural diversity.

Is it better to have 200 countries with their own various governments, or a single world government? (What if that world government was truly the best?) Is it better to read books by dozens of authors, many of which are of mediocre quality, or to repeatedly read the same one that you like most? Is it better to speak a thousand different tongues, though we don’t understand each other and have to spend a lot of time translating, or just have everybody in the world learn English?

The answers are complex and depend on what we’re looking at. Back when this blog was much smaller than it now is, I spent a few months examining them. It’s never completely obvious whether to pick a single “best” standardized option vs. encouraging a variety of competing options. Standards are useful to coordinate ourselves; diversification is useful to hedge our bets.

Quite often, though, standardization is the more immediately tempting choice. When you standardize, you can optimize; whereas diversity generally translates to suboptimality, at least in the short term. It takes a special kind of mental effort to recognize that in the long term, or at a higher level of abstraction, suboptimality is actually the more optimal choice. It feels contradictory even to write that!

Whatever the answer is for tools and devices, one could argue that we don’t get a choice anyway. The benefits of tool standardization are too great, and the incentives too irresistible, for it to be stopped. I’m inclined to agree.

Modern technology has managed to standardize because it harnessed a powerful force: the manipulation of information. Information is fast; information is protean. It provides more direct control of whatever you want to control, and can take whatever shape you want it to take. Once you’ve got some basic physical infrastructure going — a computer or smartphone — then most limits on what you can do with information are gone.

And so most new tech today is software — which is essentially the arrangement of information to achieve some purpose. The trend of converting everything to software is not going to slow down.

Still, software has its limits. It is difficult to use. Information is so powerful that we need to create a series of intermediates, like electrical transformers “from a nuclear plant to the light bulb in your house”1: logical circuits, low-level assembly language, high-level programming languages like Python and C, and from there consumer software with a graphical user interface that even your grandmother can understand. The apps in your phone are all alike, but the stuff they are made of is even more general.

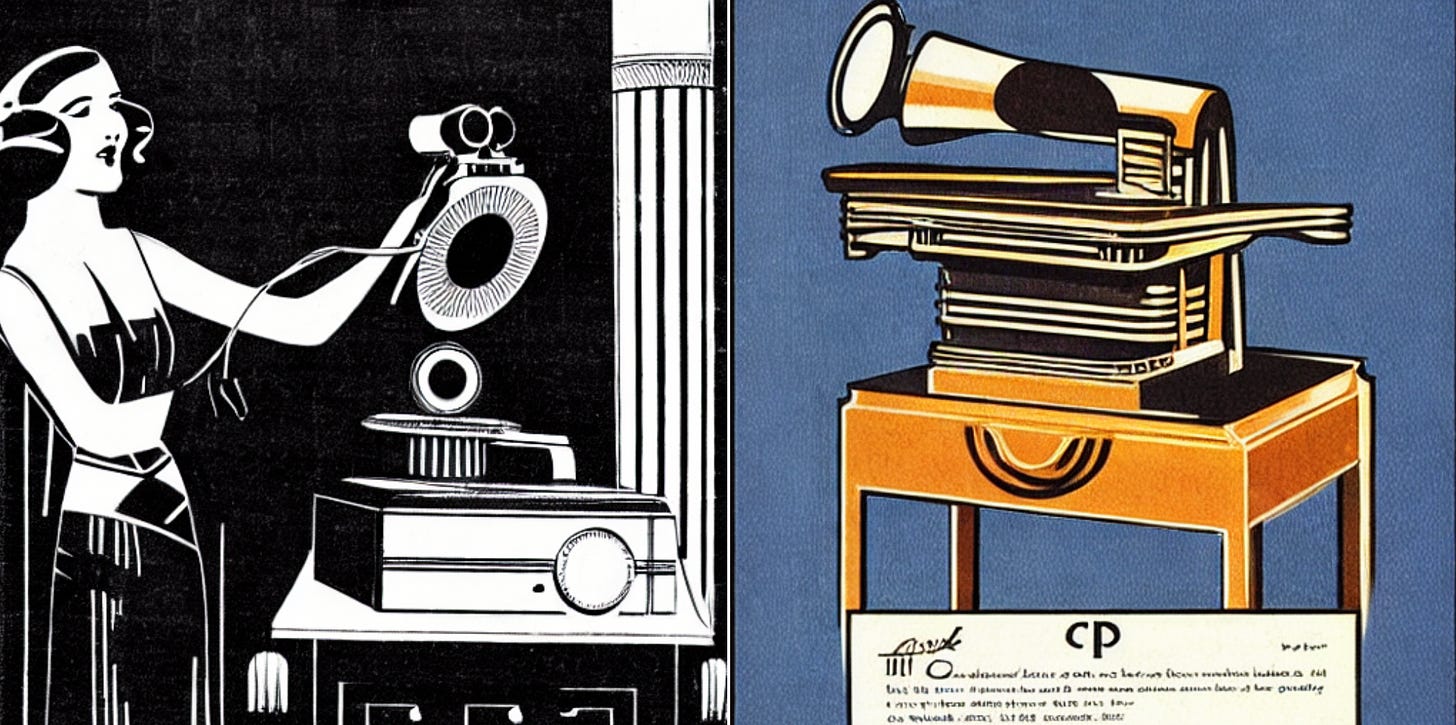

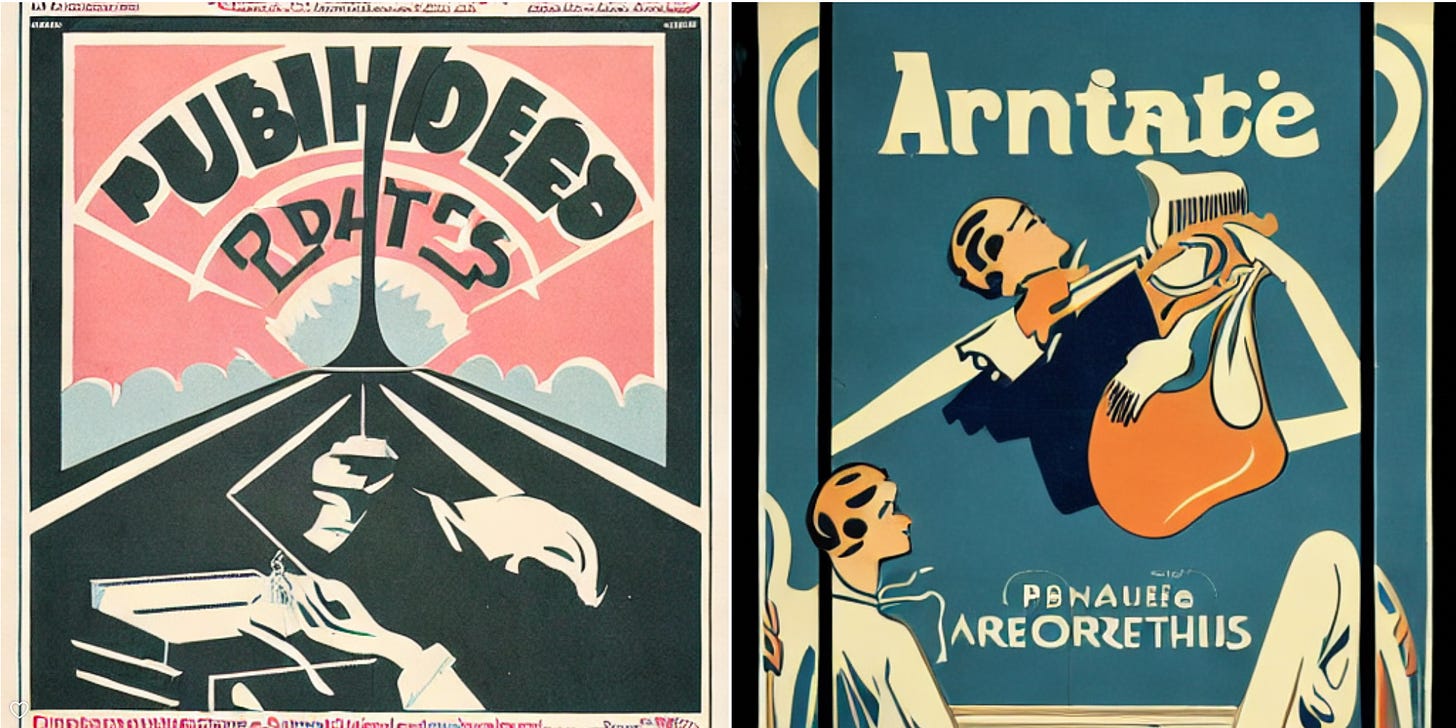

Soon, that stuff is going to be replaced by something more universal yet: natural language. We already see it in art. For most of history, painting was a complicated affair: you needed special pigments, tools like various paintbrushes, and a canvas. Later, software products such as Photoshop were invented: a single tool, made of programming languages, that bundles various subtools in its graphical user interface. And now, with AI generative art, we have something that allows us to translate our intentions into images with even fewer intermediates: just write a prompt, in regular language, and a picture shall appear.

Soon these natural language prompts will be able to also generate movies, TV shows, essays. They will — they already do — write computer code. Soon all of our technology will collapse further into a singularity made of natural language. There will be no reason to toggle anything with a physical switch, in a world where you can just ask what you need out loud.

I’m curious to see what an even more tool-standardized world will look like. There will be many great things about that world. We’ll be able to produce cultural artifacts at a rate unlike anything before. We’ll be able to access information faster. I’m optimistic that this will lead to incredible wealth, that is to say, vast improvements to our quality of life.

But it will come with the challenges of standardization. One that I can immediately see is: what about language diversity? The vast majority of current efforts in natural language processing concern English. The AI image generators that get talked about were trained on English text, and so they respond poorly to prompts in other languages.

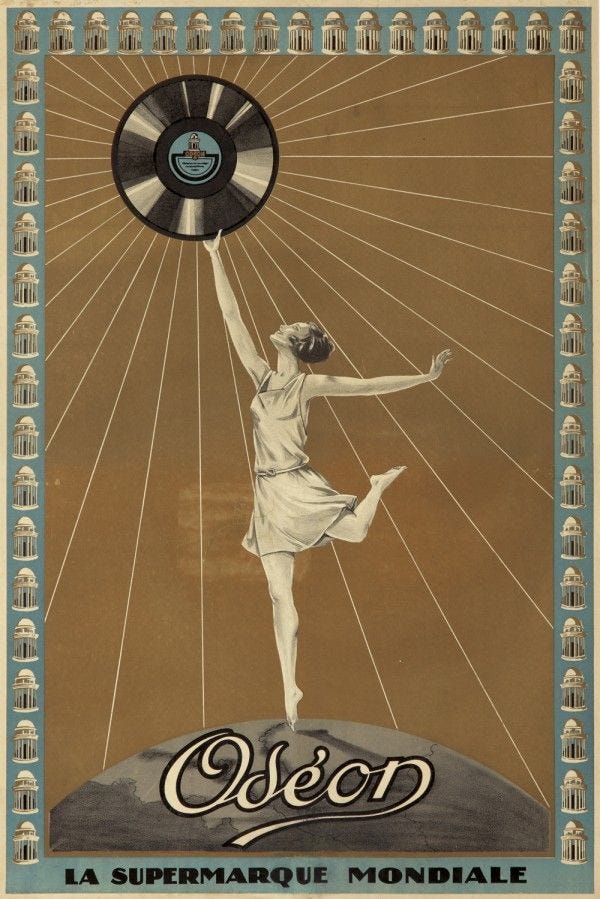

For example, here are images generated from the same prompt, first in an English version and then the equivalent French one:

We see that the outputs from the English are much more accurate. The French ones seem like generic vintage ads, and I wonder if that’s just because “art deco,” “illustration,” and “1930” are the same in both languages.

Certainly the technology will adapt to the linguistic needs of the market and eventually work well in the major languages of the world. Still, this is a concern. If language replaces all other tools, should we be worried about homogenization into a single one (or a few of them)? This question, and related ones, will be asked more and more.

And to conclude on a prediction: I suspect that in the future, we’ll come to increasingly value tool diversity. We already know that electronic books have not annihilated the market for paper ones; we already see a rebound in the sales of music vinyl records, which are less convenient but aesthetically more pleasant than streaming on Spotify. These trends will continue.

As the world gets wealthier, we will ascribe higher status to luxuries that are less than maximally convenient — ones that have nice visuals, and textures, and tactile feedback, and physical constraints, and high cost, and variety. Tool standardization will have won, and that will allow tool diversity to flourish.

that last sentence is dangerously so on point. it reminds the cycle / pendulum dynamic of so many things in our life. it comes and go, and comes again. tech changes the ‘reasons to use’ though. like back in the day you’d buy a vinyl to listen to music (without it: no music at all), now you buy it for a more specific sound style and/or because you subscribe to this lifestyle / this idea of ‘a person who owns vinyls at home’. tech might force every older versions to adapt themselves and adopt a more ‘styl-ish’ / hedonic reason to exist.