Progress Positivity in the ‘Civilization’ Games

AWM #65: The intellectual influence of video games; technology trees; the aesthetics of progress 🎮

When it comes to acknowledging our intellectual influences, we readily name books, conversations with people, films, even blog posts — but rarely do we refer to video games.

Games don’t have the cultural prestige of other media, perhaps because they are still a recent historical development, or because they tend to focus on pure entertainment as opposed to lessons on life and the universe. Yet some of us have spent countless hours on them, way too many for them not to have had an influence on our lives. In many cases this takes the form of skills, from decision-making to creativity to teamwork. But there is also a type of influence that is less talked about: something like shaping your worldview. Defining your values. Developing your thinking.

The effect can be akin to good fiction. For example, Hades, a recent rogue-like game with excellent storytelling, can teach you about forgiveness, the value of fighting over and over again for a goal, or the art of writing believable characters. Hades would not suffer from a comparison to the great works of literature.

Not all games are stories, though, and their diverse formats allow them to embed lessons in many interesting ways. For me, the most important example, the one that’s had the most effect on my thinking, is the Sid Meier’s Civilization series.

I see three ways that Civilization (a.k.a. Civ) has had an intellectual influence on me and, very likely, on many others:

Getting interested about history, and learning its basics;

Understanding the process of technological advancement;

Gaining a positive view of progress.

The rest of this post is divided into those three sections.

An Imperfect Tool to Learn History

Civilization is about controlling a civilization, like “the Japanese” or “the Aztecs” or “the Ethiopians” from the end of prehistory, around 4000 BC, until the 21st century (or whenever someone achieves victory). During your game, you’ll trade with rival civilizations and war against them; you’ll expand your territory, develop your cities, build impressive wonders of the world; and, importantly, you’ll research new technologies that allow you to progress from antiquity to the medieval era to modern times.

The obvious way a game like Civilization can influence thinking is by sparking an interest in history. A kid who knows very little about Greece, and decides to play the Greek civilization, might get hooked, go read Wikipedia about Greece, learn ancient Greek, and read the Iliad in the original text. Or not — but the possibility is there.

On the other hand, Civilization is… not quite an ideal tool to teach history. Because it is a game and not a fixed narrative, it gives flexibility and agency to the player, which allows for completely inaccurate scenarios. You can play the American civilization for a full game, from 4000 BC to 2050 AD, even though there were obviously no United States in antiquity. You can play India as immortal Gandhi,1 build the Egyptian pyramids, found Christianity, and conquer your neighbors the Vikings. You can control a totalitarian Taoist mercantilist democracy, somehow.

In short, playing the game might teach you misconceptions about history. The above examples are obvious in their wrongness, but there can be subtler ones, like thinking that productive cities are those with a bunch of mines in their vicinity, or something. It could be argued that Civilization players know less than those who don’t play and learned history from more reputable sources.

Although this can be a problem, and it would indeed be bad to claim good knowledge of history just from playing Civilization, I don’t fully agree with this line of thinking. A simplification, if you’re aware that it’s one (and with games it is pretty clear), is better than nothing at all.

Besides, the flexibility that makes the game inaccurate has a number of advantages.

First, it’s fun. You’re unlikely to ever learn history if it isn’t fun to you.

Second, being an actor is better than being a spectator. You can’t live history, but simulating it in a game is the next best thing. Acting as opposed to watching gives you a fuller picture, a better appreciation for what is happening.

Third, most ways of presenting history are zero- or one-dimensional, as I wrote at length in this essay on the shapes of history. A zero-dimensional view is a snapshot of a time and place, like a painting. A one-dimensional is either a narrative across time of a narrow part of history, like “the history of the Chinese people,” or a broad overview of a single time point, like “the state of the world in 1914.” Games are one of the few formats that allow a two-dimensional view, in which many events happen simultaneously across time, like they do in reality.

Fourth, it’s possible to customize games to make them follow real history more closely. You can play on a real Earth map as opposed to a randomly generated one, for instance. The Civilization I have played the most is a heavily fan-modified version of Civ IV , called Dawn of Civilization, that is played on such a map and adds many features to mimic real history. For instance, the Roman civilization usually collapses around 400-500 AD (in real life it was 476), and the American civilization only appears in 1775, ready to take over the European colonies in North America. My knowledge of history has greatly benefitted from playing Dawn of Civilization and discussing it on the forums.2

Finally, fifth, the flexibility completely removes any focus on specific dates, people, and events. This means you can’t learn specifically that the Battle of Teutoburg Forest opposed the Roman Empire and a coalition of Germanic tribes under their leader Arminius in 9 AD and prevented Roman expansion in the area. But you can learn that imperialistic civilizations had to deal with barbarian uprisings near their borders, that it forced them to pour their resources in the military as opposed to, say, building majestic temples, and that it delayed their conquests.

In other words, games are a good way to illustrate the mechanisms that drive history. In fact, by taking dates and names out of the equation, they might be an especially well-suited tool for this.

The most salient example, which we’ll examine in more detail, is technology.

The Technology of the Technology Tree

A technology tree is “a hierarchical visual representation of the possible sequences of upgrades a player can take (most often through the act of research).” It shows a number of technologies3 like “the wheel,” “writing,” “monotheism,” or “laser,” and how they relate to each other.

For instance, before you can discover the “spaceflight” technology, you need to research rocketry, and before that, airplanes, and before that, engines and thermodynamics, and so on until the dawn of time. And after you have discovered spaceflight, then you can invent satellites and other things.

The very idea of a technology tree was invented as part of a 1980 board game that is unrelated to the computer games we’ve been talking about, although it was also called Civilization. But tech trees did become popular and widespread thanks to being a core feature of the first Sid Meier’s Civilization video game in 1991. Since then, they’ve been used in many other strategy games.

In Civ, the tech tree is the main way a player can track their progress in the game. The eras change from antiquity to the middle ages to the industrial and modern periods when certain technologies are discovered. Technologies also determine what you can build as infrastructure in and around your cities, as well the types of military units available to you.

This turns out to be hugely important. At the beginning of the game, in the 3000s BC, everybody starts out equally primitive, with mace-wielding warriors and, after researching some basic technologies, archers, horse-drawn chariots, and spearmen. But invest a lot in research, and you will eventually invent swords made of steel, armored horsemen, and then cannons, firearms, tanks, helicopters, and nuclear missiles.

Real history is rife with examples of technologically advanced countries conquering more primitive ones. The most obvious example is probably the Europeans vs. the indigenous peoples of the New World. Civilization allows you to be Spain conquering the Inca empire with a small expeditionary force (or vice-versa). Thanks to a strong economy, or good diplomatic relations with your neighbors, or maybe espionage, you can move fast in the tech tree and become a mighty military power without investing a huge amount of resources. If you were behind, like Russia was at the time of WWI, then you could offset your technological disadvantage by raising a huge army — but this would be costly! Technological advances matter. The tech tree of Civilization teaches you that, viscerally.

It’s not exactly a groundbreaking insight that technology is important in understanding history. But the concept of a tech tree is recent enough, and niche enough, to make some of its implications not completely obvious.

One of those implications is that everything has prerequisites. Nothing is ever invented in a vacuum. This highlights the importance of thinking incrementally, if we want to discover new things. It’s possible that certain technologies — like much of basic science — won’t really be beneficial for themselves, but for the future technologies they can unlock; that’s still extremely useful.

Conversely, some technologies are dead ends. They unlock useful applications, but don’t really lead to anything more afterwards.

Another implication is that at any given position in the tree, there are multiple avenues that can be pursued — many “unlockable” techs that can be chosen. In real life, as opposed to Civ, we can research several technologies in parallel, but there’s always a question of picking, as governments, investors, and researchers, which ones we should focus on. Should we spend more on inventing nuclear fusion, improving nuclear fission, developing solar energy, capturing carbon from fossil fuels, or encouraging people to consume less?

Recently, there have been suggestions to use technology trees in real life to map out the future developments in certain fields. For example, Balaji Srinivasan:

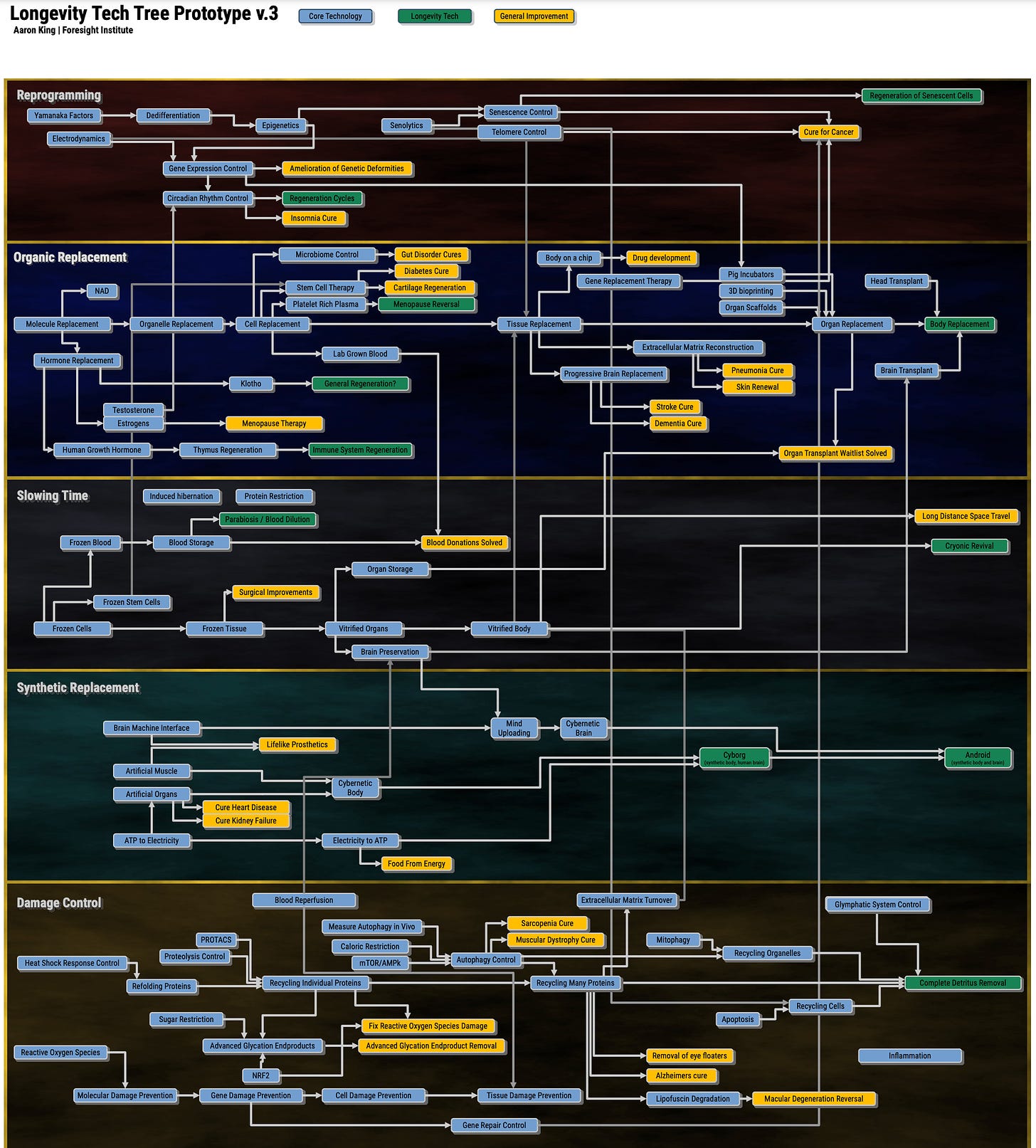

An example of this, applied to the specific field of research in aging, is the longevity tech tree created by Aaron King at the Foresight Institute:

Of course, you could say that this picture is just a fancy flowchart. And yes, they’re not a revolutionary idea. But I do believe that they represent an improvement in the way we think about technological progress. Without the concept of a tree, you won’t necessarily have a good model of how progress can happen at all. It would be like navigating an area without a map.

Put differently, tech trees make progress visible. This in turns helps us believing that progress is real, and desirable.

Positive Visions of Progress

Let’s talk about the aesthetics of the Civilization series for a moment.

You already saw the cover artwork for the first four games in the series. Here are the last two:

All the Civilization covers express certain ideals. “Building” is a major one: the tower of Babel in III, cities and various monuments in the others. There’s also an ideal of diversity: this is a game about the many civilizations of the world, from ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia to modern France, America, or Brazil.

And then there is the ideal of progress.

Consider Civilization V. It’s not that clear from its cover artwork above, but that game’s visual design was completely based on the Art Deco aesthetic. The main menu screen might drive the point home:

Art Deco is often associated with technological progress. It was dominant in the 1920s and 30s, when technological progress was more in vogue than it is today — when it still felt that mastering the world could be done and was a good thing to do. “As a style, Art Deco asks us to pursue progress without forgetting the divine,” wrote David Perell.

Art Deco today is generally beloved, and yet rarely ever used in architecture or design. Civilization V is an exception. I don’t think it’s a coincidental one. It embodies a certain ideal — the ideal that progress is good and desirable. Let’s call that progress positivity.

Now consider Civilization VI. Visually, its cover art and main menu are not eveidently progress-positive. Musically, however — well, just listen to its main theme. It’s worth it.

This theme, composed by Christopher Tin, is Sogno di Volare. The Dream of Flight. Lyrics by Leonardo da Vinci, on “being lifted by our own creation, just like the birds, towards the sky, filling the universe with wonder and glory.”

As one of the commenters under the YouTube video puts it, “it's hard to get more badass than ‘Lyrics by Leonardo da Vinci.’”

In fact, I suggest reading some of the top comments on the video. They’re great. Somebody says they were inspired by the song to get their pilot’s license. Others say it should be an anthem for humanity. The video itself has almost 14 million views, which is considerable for a piece of classical music.

And as if this was not epic enough, Christopher Tin wrote an entire oratorio on this theme, called To Shiver the Sky. It sets to music the words of “astronomers, inventors, visionaries and pilots” such as Nicolas Copernicus, Jules Verne, and Yuri Gagarin. Highly recommended.

This is incredibly progress-positive music. It’s about exploring and inventing, breaking free of our constraints, claiming “our place among the stars.” With this, and the Art Deco style of Civ V, and related artwork in previous games, it seems clear that the artistic teams behind the various Civilization games have adopted a vision that extol technological progress.

Plus, as we saw in our discussion of tech trees, progress plays an enormous role in the gameplay. Of course, during a game, you might use progress for warfare and destruction. You can invent nukes and raze all of your opponents’ major cities to the ground before they have a chance to, if you want to. This is not naïve techno-optimism: Civilization recognizes that tech can be used for evil. But it also gives you the opportunity to use it for good. You can use progress to build monumental wonders of the world, prosperous cities, intricate trade networks, or a spaceship to colonize new worlds. Civilization allows multiple types of victory: militarily, for which progress will help in dominating your enemies, but also culturally, scientifically, or diplomatically.

All of that is to say: the Civilization games are extremely progress-positive pieces of media, both by their nature and by their presentation.

This is, unfortunately, unusual.

Progress positivity is not that common in the zeitgeist of the 21st century. As Jason Crawford, who seeks to develop a new philosophy of progress, wrote:

We live in an age that has lost its optimism. Polls show that people think the world is getting worse, not better. Children fear dying from environmental catastrophe before they reach old age. Technologists are as likely to be told that they are ruining society as that they are bettering it.

It seems very plausible that this is reflected in our art and media. Science fiction is more often dystopian than inspiring. The Chinese SF novel The Three-Body Problem and its trilogy carry a sad message that innovation and problem-solving don’t really matter in the grand scheme of things. The movie Don’t Look Up could have been about using technology to save humanity, but instead has a big tech company come in and make everything worse.

But some people, including Jason Crawford and others involved in what is now called “progress studies,” like Tyler Cowen and Patrick Collison, have been trying to revive interest in technological progress. If done well, they argue, progress can solve many of our problems and create vastly more prosperity than stagnation or (God forbid) degrowth.

Encouraging progress is a worthy goal. And if it succeeds, part of it will be by inspiring artists and designers to create more progress-positive art, like the Art Deco people did a century ago — which will in turn inspire society as a whole.

I know Jason didn’t play Civilization (I asked), but I wouldn’t be surprised if it was the case for a significant proportion of those who are attracted by progress studies. On myself, at least, they’ve had an intellectual impact this way.

The Sid Meier’s Civilization games have been very popular in the past thirty years, and they have been holding the torch of progress positivity at a time when it was not burning strong. They show that it is possible to create and sell positive, yet non-naïve, visions of technology.

I suggest we create more.

This is a good opportunity to mention Nuclear Gandhi, a hilarious meme that stems from an urban legend about the first Civ game, in which an integer overflow bug could allegedly turn Gandhi from the most pacifist leader to the most aggressive one (and proceed to attack everybody with nuclear weapons).

And then, of course, there are other grand strategy games besides Civilization. The ones by Paradox Interactive, like Europa Universalis, seem to be designed to simulate history far more accurately than Civilization, but I have never really played them.

Civilization uses the word technology in a broad sense, comprising everything from scientific and philosophical advances to new types of social organization, religious concepts, and physical inventions.