Sun Worship So Intense It Disrupts the Entire Country

Review of “Egypt’s Golden Couple: When Akhenaten and Nefertiti Were Gods on Earth” 🌞

I submitted this book review to the ACX Book Review Contest, but it wasn’t selected by readers as a finalist, so I’m releasing it now. (I can’t believe I messed up and didn’t publish such a sun-themed essay last week on the exact time of the summer solstice!)

A puzzle: Why does the Sun not play a larger role in religion? It is by far the most powerful object we witness in daily life; it gives life to everything, and it marks the passage of time. Its workings weren’t understood until modern science, making it clearly magical. Yet it doesn’t feature prominently in any of the great monotheisms or other modern religions. It usually appears as a god in polytheism, but rarely as a central or especially important one. Why not?

A possible answer: It’s been tried before. And it didn’t go well.

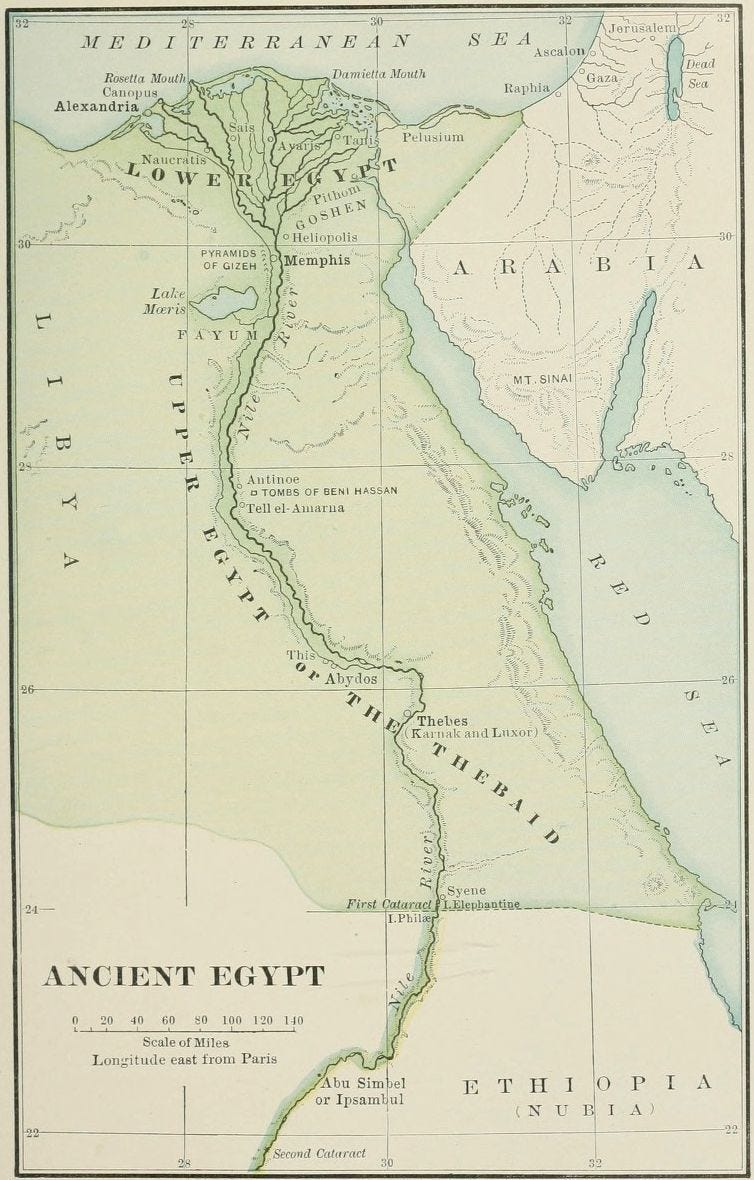

𓏺.

The first reason to read about Pharaoh Akhenaten (born at some point before 1363 BC, died in either 1336 or 1334 BC) is his maybe-monotheistic sun cult, a unique occurrence in history. After a few years of more-or-less normal reign under the name Amunhotep IV, he elevated the sun disk, in Egyptian called the Aten, as the main or even sole god of the pantheon. He then renamed himself Akhenaten (“Effective for the Aten”), and he moved the capital from Waset, a.k.a. Thebes or Luxor, to a new planned city with an annoyingly similar name to his own, Akhet-Aten (“Horizon of the Aten”). This turned out to be rather disruptive to the ancient Egyptian people, and after Akhenaten’s death, 17 years into his reign, the traditional religion was restored. Most of his legacy was erased, often literally by chiseling away his face from reliefs and statues. Later pharaohs went so far as to remove him and his immediate successors from king lists, as if they hadn’t existed. If they had to refer to him, they obliquely called him “the enemy of Akhet-Aten”.

It’s a dramatic story, perhaps the most interesting one out of the millennia of ancient Egyptian history. Akhenaten has been called “the world’s first individual” because of his supposed freethinking, outside of traditional religion; less theatrically, he has been seen as “the first monotheist”, foreshadowing Moses and Jesus. Sigmund Freud used him as proof of his Oedipal complex (obviously his radical actions stemmed from his complicated relationship with his father, Amunhotep III). Others called him mad, revolutionary, incestuous, totalitarian, messianic, physically weak, effeminate, morally corrupt, etc.

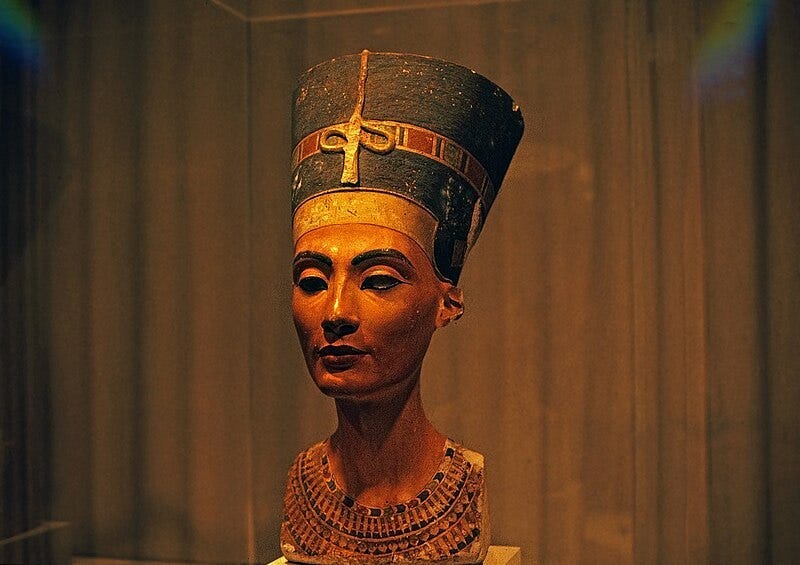

The second reason to read about him is that he was married to this woman:

This is Nefertiti, as represented in a bust carved by the sculptor Thutmose (quite amazing that we know the artist’s name!) in 1345 BC. This piece is probably the second-most famous artifact from ancient Egypt. It ended up in Germany due to either intentional deception from the German archeologists or an administrative mistake by the French-led Egyptian Antiquities Service, and is now a main attraction of the Neues Museum in Berlin, where I once photographed it despite not being allowed to:

Nefertiti, besides being a beautiful woman whose name literally means “the beautiful one has come”, was Akhenaten’s Great Royal Wife and maybe his co-ruler, as well as a candidate for being the female pharaoh of uncertain identity who reigned for a short time after his death (and the short reign of an equally mysterious male pharaoh). It’s clear from the evidence that she and Akhenaten formed a power couple, one that happened to rule in the middle of Egypt’s peak of power and prestige and messed up everything.

Why is her bust only the second-most famous Egyptian artifact? Because, of course, it is outshone by this other artifact, the death mask of Pharaoh Tutankhamun:1

What you may not know about Tutankhamun is that his birth name was actually Tutankhaten (“Living Image of Aten”). He was probably the son of Akhenaten, and definitely his successor after a short interlude consisting of Mysterious-Male-Pharaoh and Mysterious-Female-Pharaoh-Who-Was-Maybe-Nefertiti-Or-Maybe-Meritaten. In fact, Tutankhamun is the one who restored the traditional religion after the upheaval caused by his father, which you can tell from how he changed his name (Aten → Amun), before dying at the tender age of 18 or 19 and being immortalized with the most awesome funerary mask ever made.

King Tut is of course the most famous out of the at least 170 (and possibly more than 300) pharaohs who reigned from 3150 to 30 BC, thanks to the mask and the allegedly cursed discovery of his tomb a hundred years ago. So his relationship to Akhenaten provides us with a third reason to study him and his reign — although one that we didn’t need, and one that we won’t focus on, since the book being reviewed here is specifically about Akhenaten and Nefertiti. It is called Egypt’s Golden Couple: When Akhenaten and Nefertiti Were Gods on Earth.

While we’re here, I’ll mention a bonus fourth reason to read this book: it was written in 2022 by another power couple, John and Colleen Darnell, American Egyptologists who happen to also be known as fashion models. Look at them, as seen on Dr. Colleen Darnell’s Instagram account vintage_egyptologist, sailing on the Nile as if this were the 1920s or 30s:

Apparently they’re a bit controversial! Not only did she rise in the ranks of the Egyptology department at Yale while dating him, an already married professor — a sexual scandal that tarnished the department’s reputation; but also, their love of early 20th-century clothing and photoshoots among the ruins of Egypt has been heavily criticized as distasteful at best, and as insensitive “colonial cosplay” at worst. None of this matters for the book, which is considered to be scholarly sound. But it’s another dramatic story! Sure, the Darnells may just be trying to attract attention — and it works! I was far more excited to read their book than another on Akhenaten that I attempted to dig into before narrowly escaping death by boredom.

But enough about them; let’s go back to their book. Who were Akhenaten and Nefertiti? And what made them want to overhaul society, deemphasize the traditional gods of Egypt, and only worship the Sun Disk?

𓏻.

Amunhotep IV, the future Akhenaten, was born a prince to Amunhotep III, ninth pharaoh of the 18th dynasty in the New Kingdom period. If you know anything about the periodization of Egyptian history, you’re probably aware that the New Kingdom is considered the golden age of Egyptian civilization; and the 18th dynasty may be seen as the peak of that golden age, rivaled only by the reign of Ramesses II in the 19th dynasty. Amunhotep III, who ruled for 37 or 38 years, is widely regarded as one of the greatest pharaohs of ancient Egypt.

Amunhotep III also holds the distinction of being the pharaoh with the most extant statues, about 250. Here he is represented by the two Colossi of Memnon, which still stand on the western outskirts of Luxor:

The Darnells (and I) bring up Amunhotep III in part to provide context on Akhenaten’s early life, so that we know he was born in a period of unparalleled prosperity and kingly power. But the other goal is to show that Akhenaten’s later actions were less unprecedented than it may seem at first glance.

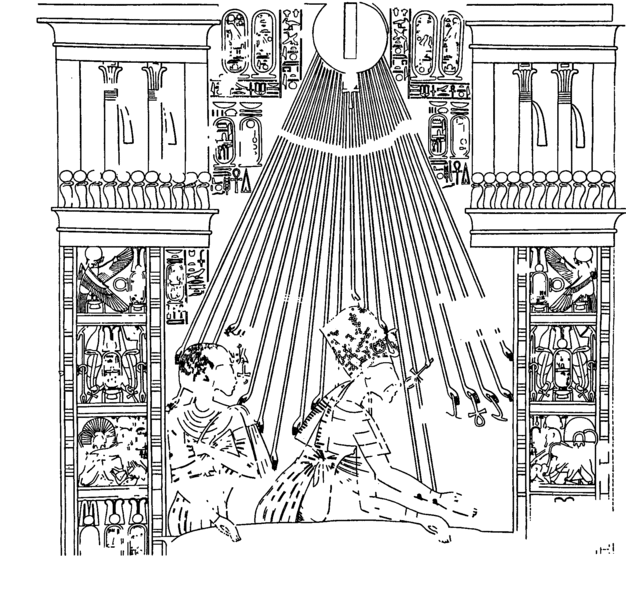

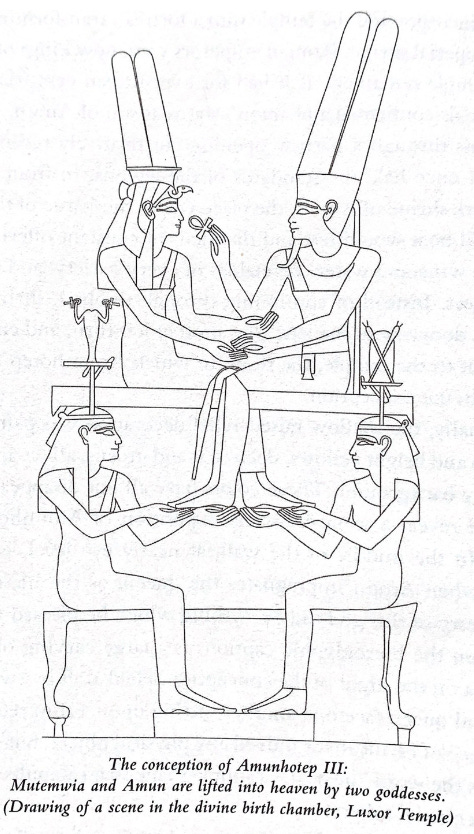

For example, there exists a text, created during Amunhotep III’s reign, telling of his conception by his mother, Mutemwia, and the god Amun-Re. Amun, during the New Kingdom period, rose from being the patron god of the city of Waset to reigning as the top god of the whole Egyptian pantheon, later being seen as an equivalent to Zeus and Jupiter. Eventually, he was merged with Re (or Ra), the famous sun god who was among the most important deities during earlier periods. So it made sense for Amunhotep III — whose name means “Amun is satisfied” — to claim that he was literally “one flesh” with Amun-Re thanks to the union of the king of the gods with his mother. We even have a depiction of the sexual act (don’t worry, it’s very tame):

The Darnells tell us that “an ancient Egyptian would have noted the erotic overtones of Amun’s legs overlapping those of Mutemwia, how she cups the god’s elbow with her free hand, and he holds to her nose the hieroglyph for ‘life,’ the ankh sign. . . . the sexual nature of the scene is obvious.”

Anyway, the point is that Akhenaten’s father was already claiming to be descending from the sun god. It was written that he would “rule all that the sun disk [the aten] encircles”, a popular turn of phrase that pharaohs had been using for generations. And to celebrate his 30th regnal year, he resurrected an extremely ancient festival — the only evidence we have for it dates from around 3000 BC, so more than 1,600 years prior — that involved sailing on boats representing the travel of the solar deity Re in the sky (during the day) and the underworld (during the night). “The king,” write the Darnells, “was expected to merge with Re after his death, but Amunhotep III did something unprecedented: he sailed in the Day Bark and the Night Bark while still alive.” (Emphasis theirs.)

Also, just like his son would later do on a grander scale with his new city, Amunhotep III built a new palace complex near Waset, called Malqata, from which many surviving inscriptions show that he liked calling himself the “Dazzling Sun Disk”. So by the time Akhenaten became pharaoh, at the age of somewhere between 10 and 23 (the Darnells’ best guess is 13 or 14), the theme of identifying the king with the Aten was very much in the air.

𓏼.

At first, Akhenaten — then still called “Amun is satisfied”, fourth of his name, and reigning from Waset — modestly continued the work of his father. Amunhotep III had been adding parts to the great temple of Amun-Re at the Karnak complex, near the capital. Out of filial duty, Amunhotep IV completed some of them.

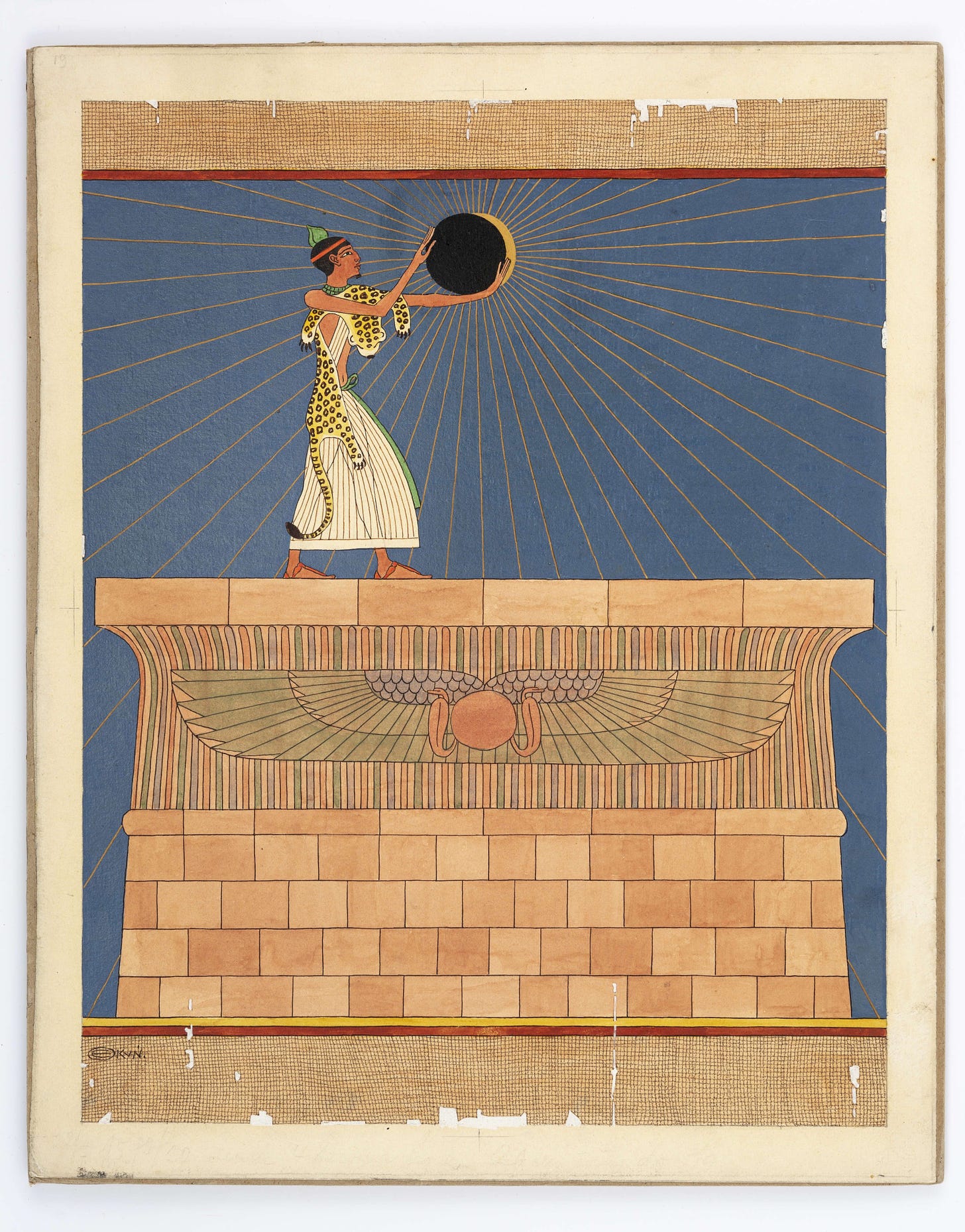

But almost immediately, he seems to have shifted the focus away from Amun-Re and towards a deified sun disk. Many of the temples he added to Karnak are Aten-themed, bearing names like “The Sun Disk is Found”, “Sturdy are the Monuments of the Sun Disk Forever”, and “Exalted are the Monuments of the Sun Disk Forever”. In another of these temples, the Mansion of the Benben, he ordered the construction of a new Great Benben, a sacred obelisk, dedicated not to Amun but to “Re-Horus of the Horizon in his name of light who is in the sun disk”, one of the more complicated ways to refer to Aten.

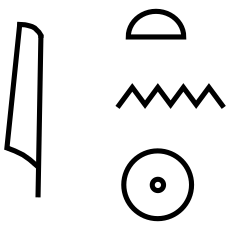

The Darnells explain that this shift in focus would have been unusual, but not overly so. The Benben, a representation of the first mound of land at the time of creation, had been an inspiration for sacred monuments at least since the Giza pyramids; dedicating it to a form of the sun god was “the continuation of solar worship that began over a thousand years before.” And the word “aten”, written with four hieroglyphs, 𓇋, 𓏏, 𓈖, and 𓇳, had been a common noun to refer to the sun as a disk in religious contexts since at least 2350 BC.

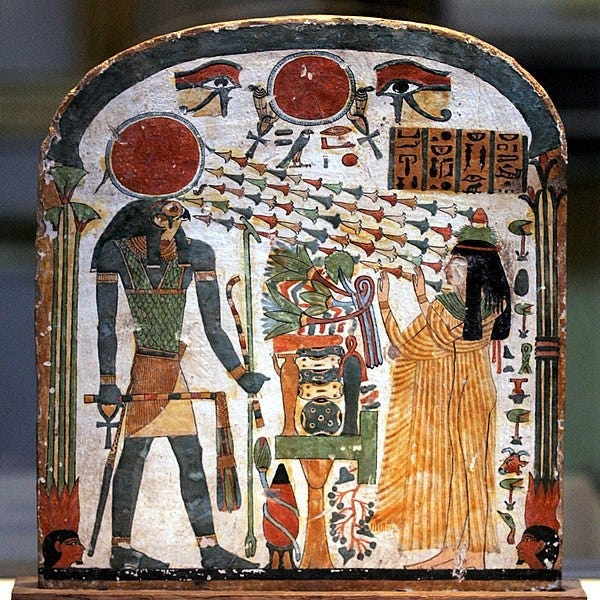

On the other hand, describing the actual disk as the solar god was clearly strange. Usually, Egyptian gods were human-shaped, animal-shaped, or human-animal hybrids (though there were exceptions). An aten could be an attribute of a god with an otherwise normal body; for example it is often seen on top of Re’s head, whatever shape that head had (human, falcon, ram, beetle). But to depict as a deity the sun disk itself, round and often featureless except for rays terminating with hands holding the ankh sign, was totally new.

Why did this theological change happen? Since the discovery of Akhenaten’s existence in the 19th century, people have loved speculating about this. A popular explanation involves the supposed corruption of the Karnak priests of Amun: in this view, the pharaoh was a visionary leader who sought to diminish the power of a clergy more concerned with its own wealth and hedonism than the religious welfare of the people. Another view, perhaps taking inspiration from other tales of religious reformers, imagines him having received a prophetic revelation in a dream. Some also speculate that the religion came from the influence of his mother, Queen Tiye.

The problem with these theories is that there’s literally nothing to support them. They’re just guesses.

At the risk of stating the obvious, a difficulty when studying a figure who lived 3,300 years ago is that often, the only evidence you have is a single extremely fragmentary text whose meaning depends wildly on interpretation. Chapter 11 of Egypt’s Golden Couple is a rather fascinating dive into one such piece of evidence, from Karnak, the only known inscription that provides a clue for the development of Atenism. Here is the translation given in the book, with tons of brackets to indicate missing and reconstructed text. See if you can make sense of it:

[. . .] Horus(?) [. . .]

[. . . temples(?) fallen into] ruin, without any (divine) beings [. . .]

[. . . royal(?)] august ones(?),” so say the knowledgeable ones [. . .]Behold, I am speaking that I might cause (you) to know [. . .]

[. . .] manifestations of the gods, so that I might understand the temples [. . .]

[. . .] writings of the inventory of their majesties, the antiquity [. . .]

[. . .] which they desire, one after another, out of all precious stones [. . .][. . . who bore] himself, [whose] secrets cannot be known [. . .]

[. . .] he [coming(?)] to the place he has desired. They will not know his going [. . .]

[. . .] night; but I approach(?) [. . .]

[. . .] which he made, how exalted are they [. . .]

[. . .] their [. . .]s as stars. Hail to you in your rays [. . .]

[. . .] What is he like, another like you? You are [. . .]

[. . .] they [. . .] in that your name [. . .]

The Darnells explain that there are three sections, which I separated with paragraph breaks above: (1) “a description of the sad state of affairs the king as discovered” ; (2) “a proclamation of the royal solution to that awful situation”; and (3) “a hymn to the solar deity”. They further point out that this text has many parallels during the rule of earlier pharaohs: it was common to describe the king as the only person capable of solving a problem, like the temples having fallen into ruin. And here the solution seems to involve Aten, whose movements are unknowable and who has no other like him.

The interpretation of the middle part hinges on one verb, which I put in bold above. The Darnells translate it as “desire”, but earlier Egyptologists believed it was “cease”, as in “the statues of the gods in temples have ceased to work”. If you’re interested in the linguistics of Egyptian hieroglyphs, their explanation for this choice is worth reading. But to get to the point, their argument is that the previous view, which held that this text was a manifesto claiming that all the gods had ceased to be powerful except for Aten, is likely wrong. Instead the gods “desire” statues, and Amunhotep IV will be inventorying them in the temples across Egypt. There’s another record of such an accounting effort being made by him, so it fits. Conclusion: although Amunhotep IV was clearly already a pretty big fan of Aten, he was less monotheistic in his early reign as one may think. He was okay with the existence of other cults, and indeed would benefit from them by levying taxes on the temples.

It’s a less interesting story; it unfortunately tells us less about Amunhotep IV’s choice to worship Aten than we might have hoped. That’s what you get when you pay attention to the actual hieroglyphs, I suppose.

𓏽.

Amunhotep IV spent five years ruling from Waset in what can be seen as a transition period between the reign of his father and his more radical phase in his new capital city. The chronology of the events during this time isn’t always clear and this whole part of the Darnells’ book is somewhat confusing to read, but in addition to the theological reforms above, we know that:

He married Nefertiti.

He dedicated the Mansion of the Benben to her. In this temple, she is shown bearing the name Neferneferuaten (“Beautiful is the beauty of Aten”), making offerings to Aten, and smiting enemies. It was already clear, only a few years into their joint reign, that Nefertiti had an important role in Atenism.

He began commissioning art in a revolutionary new style, today called Amarna art, with unusual ways to represent the king and queen, among other details. This is notable since Egyptian art tended to be conservative and changed little over centuries.

He had his first daughter out of six, Meritaten (“She who is beloved of the Aten”).

He and Nefertiti celebrated their jubilee. A jubilee, or Sed festival, was something you celebrated when you had reigned for 30 years, and then every 3-4 years after that. Amunhotep IV didn’t wait 30 years; he celebrated it in his 3rd or 4th regnal year. Charitably, the Darnells say it could have been meant as a continuation of the sequence of jubilees at the end of Amunhotep III’s reign. Either way, it was probably intended to make it clear to everyone that Aten was now more important than all the other gods, with unique rituals such as presenting food offerings to the sun in open-roofed kiosks.

Eventually, though, Amunhotep IV had greater ambitions. We (think we) know the exact date of the foundation of his sacred city, Akhet-Aten: February 22, 1347 BC. Precise records exist thanks to a set of “boundary stelae” that were carved into the cliffs at the edges of the new city — the most important textual evidence we have of the period. On one of them, we can read this proclamation by the king (I recommend reading it out loud in a declamatory style):

It is in this very place that I shall make Horizon of Aten [Akhet-Aten] for Aten, my father! I shall not make Horizon of Aten for him south of it, north of it, west of it, or east of it. I shall not go beyond the southern stela of Horizon of Aten toward the south, nor shall I go beyond the northern stela of Horizon of Aten toward the north, to make Horizon of Aten for him there. Nor shall I make it for him on the western side of Horizon of Aten. It is on the eastern side of Horizon of Aten that I shall make Horizon of Aten for Aten, my father—the place he made—that it might be encompassed for him by the mountain itself. Just as he shall attain happiness in it, so shall I offer to him in it. This is it!

A couple of things to note: first, Akhenaten refers to Aten as his father, as Amunhotep III had done with Amun; on other stelae, he also insists that the idea of founding the new city came from “Aten, my father”. Second, that’s quite a lot of insisting that this is the best place for the new city, and nowhere else. There’s even another stela where he warns Nefertiti not to tell him, “Look, there is a good place for Akhet-Aten in another place”; he adds, “I will not listen to her!”

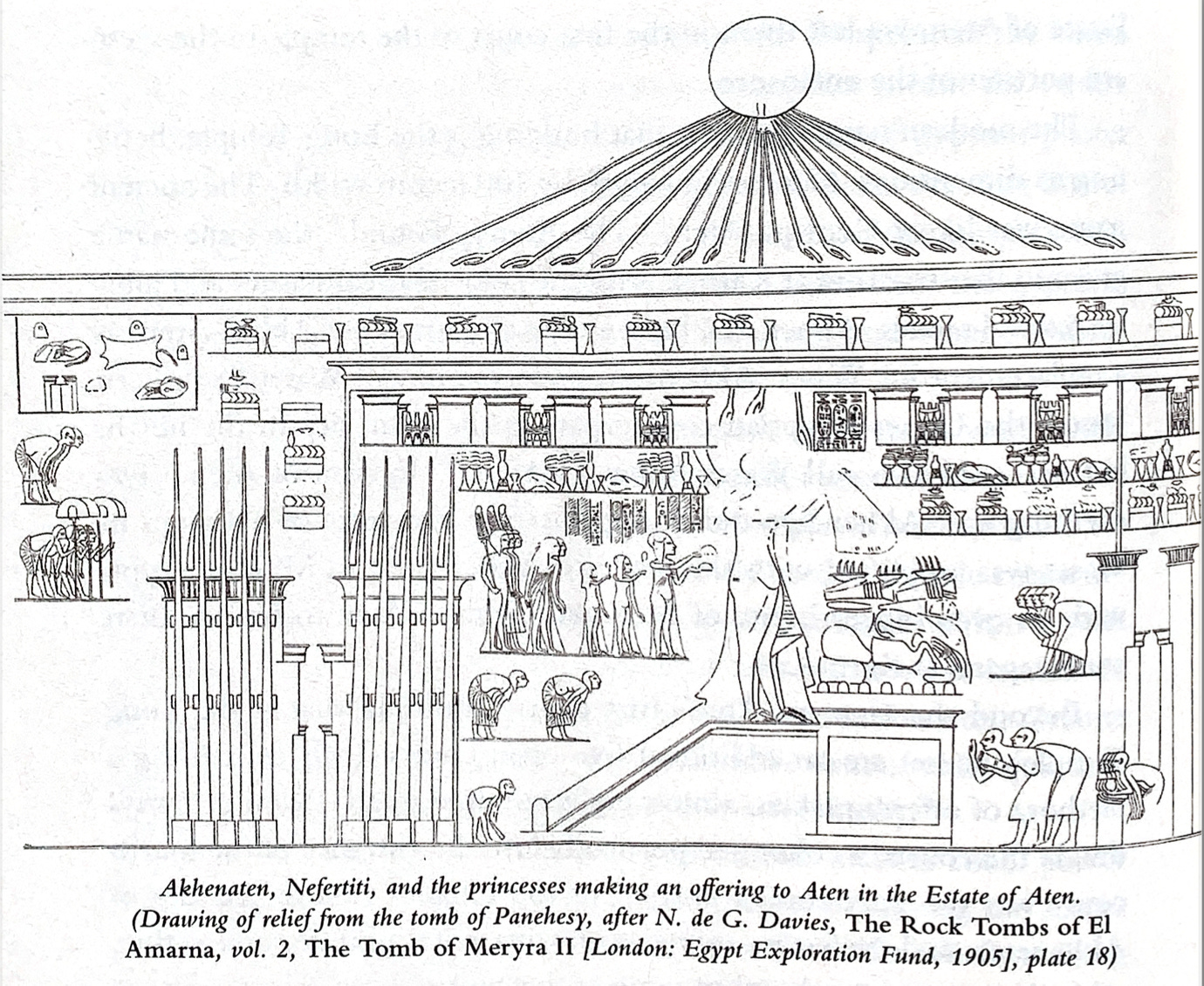

Some of the other stelae are essentially lists of all the palaces and temples the king intended to build “for Aten, my father, in Akhet-Aten, in this very place.” For example, “the Estate of Aten, for Aten, my father, in Akhet-Aten, in this very place.” Or “the Mansion of Aten, for Aten my father, in Akhet-Aten, in this very place.” The pharaoh even says he will collect taxes to be “at the disposal of the Aten, my father in Akhet-Aten, in this very place.” One wonders if Egyptian proclamations were always this repetitive. At the very least, they show that the king’s devotion to Aten, his father, makes absolutely no doubt.

Oh, also — the stelae are the first documents on which he is called Akhenaten, rather than Amunhotep IV. A new phase in his life and reign had begun.

𓏾.

Akhet-Aten is today better known as Amarna or Tell el-Amarna, which are modern Arabic names. It is about halfway between Waset/Thebes/Luxor and Memphis/Cairo, nowhere near any big modern city. The site was also uninhabited when Akhenaten selected it.

Akhenaten and Nefertiti ruled Egypt from Akhet-Aten for twelve years. Much of the second half of the Darnells’ book is on the city and what we know from their life there. Even though the most interesting feature of that period is the increasingly radical religion of Atenism, it’s important to remember that Akhet-Aten was also a normal capital city, housing some 30,000 people. To get an idea of what it may have looked like, I recommend the illustrations by the architect and archeologist Jean-Claude Golvin.

Because it was abandoned shortly after Akhenaten’s death and has remained uninhabited since then, Akhet-Aten is the source of many a great archeological find. The workshop of the sculptor Thutmose was there; it gave us the bust of Nefertiti. There was an “Office of the Correspondence of Pharaoh” in which hundreds of letters were found; they’re written in Akkadian cuneiform, on clay tablets, and tell us a lot about the foreign relations of Egypt with the Middle East.

And then there were the actual temples and palaces. The two main temples to Aten — the Estate and the Mansion — were grander than their equivalents in Karnak. They were “open to the sky, the light-drenched spaces showing the god’s immanence within the sacred enclosure”. In the immense Estate of Aten, there were almost two thousand outdoor tables where the population of the city could pile up gigantic quantities of food as offerings to the sun disk. Fortunately, the Darnells reassure us that Aten had “no use for rotting meat and wilting lettuce, so people then consumed the actual calories after the sun disk had soaked up the metaphysical essence of the food.”

But the most enlightening find from Akhet-Aten, at least from the point of view of studying Atenism, has to be the Great Hymn to Aten.

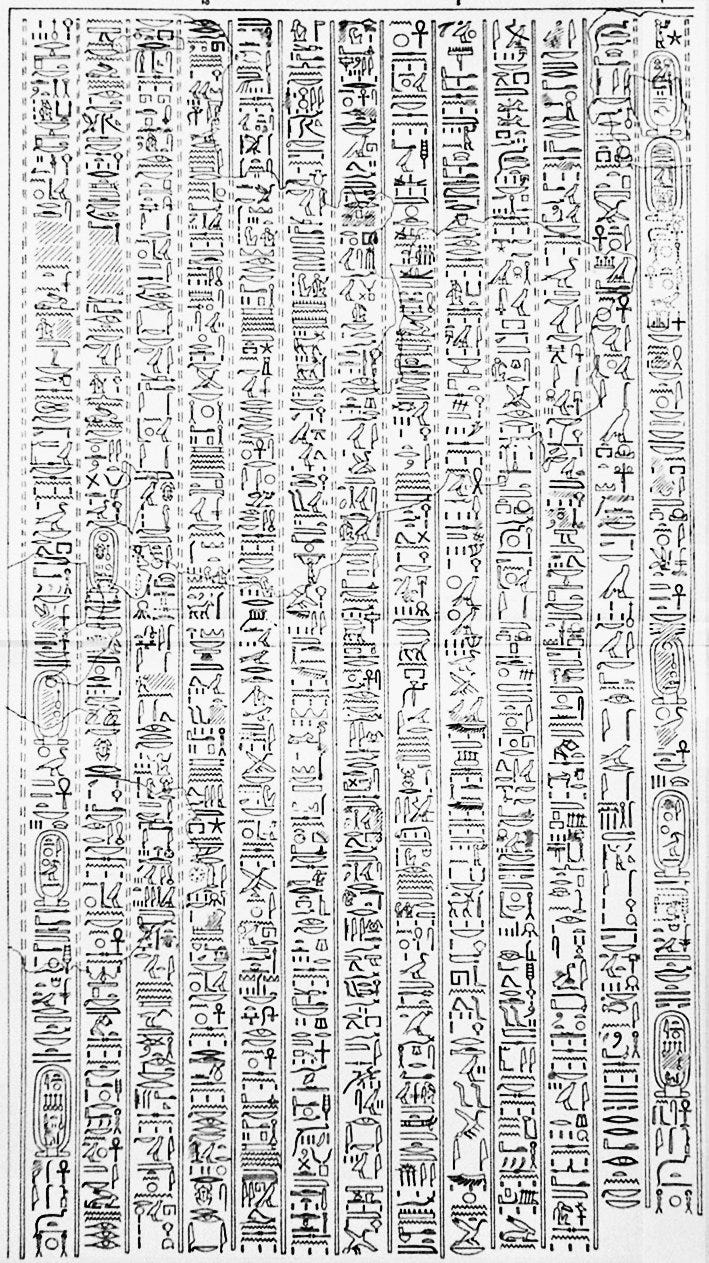

It was discovered, almost undamaged, on the wall of a tomb intended for the courtier Ay — but which was never used since Ay survived Akhenaten and even became pharaoh after Tutankhamun. It is a long poem, the longest text from the period, in fact, other than the boundary stelae. It is written as if Ay were speaking, but it’s plausible that Akhenaten himself composed it. Here it is in full:

If you can’t read Egyptian hieroglyphs, you may want to look up one of the many translations that exist out there. Or you could listen to part of it in song, set to the beautiful operatic music of Philip Glass. The Darnells, like everyone who has ever written a book about Akhenaten, also provide their own translation. I won’t reproduce it its entirety, but here are some choice quotes.

The first few verses, on how Aten is awesome when he rises in the East:

May you appear beautifully in the horizon of heaven, o living Aten,

who initiates life,

you having arisen in the eastern horizon.

That you have filled every land with your perfection,

is with you being beautiful, great, dazzling, and high over every land.

On how everything becomes much worse at night, when Aten isn’t around—a time for thieves, lions, snakes, and death:

When you go to rest in the western horizon,

the land is in darkness in the manner of death,

the sleepers in the bedchamber, heads covered.

No eye can see another,

so that all their possessions could be stolen—although they are beneath

their heads—without them knowing.

Every lion comes forth from his den.

All serpents bite.

The shrine grows dark, the land is silent.

The one who made them has gone to rest in his horizon.

On how Aten is the only god and creator:

How many are your deeds,

although they are hidden from sight.

The sole god with no other beside him.

You created the earth according to your desire,

you being alone

On how Aten is good even to the foreigners outside Egypt, being responsible, among other things, for rain (recall that Egyptian agriculture depends on the flooding of the Nile, not rain):

As for all distant foreign lands,

you make them live.

That it might descend for them have you placed an inundation in heaven.

That it makes waves upon the mountains like the sea

is in order to water their fields with what pertains to them.

(It’s pretty cool that the Hymn seems to attribute the water cycle to solar energy, which is correct, although I assume it’s more an expression of generic divine power than a scientific explanation. I’ve read elsewhere that Akhenaten, in addition to being “the first individual” and “the first monotheist”, was also “the first scientist” because his poetry displays some understanding of the effects of the sun on nature, though to be honest that seems like a stretch and the Darnells don’t even bring it up.)

And lastly, on how Akhenaten (here referred to by another of his names, Neferkheperure, Unique One of Re) is the only person who is able to “know” Aten:

There is no other one who knows you,

except for your son, Neferkheperure, Unique One of Re,

whom you cause to become aware of your plans and your power

As it turns out, this last bit may be the most important clue to explain Akhenaten’s theology. It seems that the pharaoh’s new cult had the effect of concentrating religious power onto his own person. “People can see the disk and feel its heat,” write the Darnells, “but Aten is otherwise mute. Unlike other gods, Aten does not speak to anyone except the royal family. . . . At Akhet-Aten, even the high priests of Aten only interacted directly with the king, who acted as the intermediary between the priests and the gods they served.”

It goes further. In the tomb of one of those high priests, there’s a passage on how Akhenaten is “one who lives on maat”. Maat is a complicated concept we might translate as “cosmic order”. It was expected of pharaohs that they would ensure cosmic order remained in place, but Akhenaten went beyond that. The Darnells write that he “transgressed royal norms and usurped the role of a deity: he does not just ‘bring about’ maat, as was the king’s duty, but lives on maat. Kings offer maat to the gods, but only gods live on maat.”

Elsewhere we see an interesting parallel: a priest at Karnak wrote on a wall, shortly after Akhenaten’s death (and therefore still during the period of official Atenism), a lament on how he felt abandoned by Amun, saying, “Joyous is the person who sees you, o Amun! He is in festival every day.” Meanwhile, at Akhet-Aten, a tomb hymn ends with “Joyous is one who follows the ruler! He is in festival every day.” Another sign that the pharaoh had usurped the role of the king of the gods.

So, was Atenism a form of monotheism? That depends on the precise definition, but you could argue for no: it elevated Akhenaten — and Nefertiti, who had a far more prominent role than queens usually got — as deities, forming a trinity together with Aten. The king and queen worshiped the Sun Disk, and everyone else, even high priests of Aten, worshiped the king and queen. People even had little stelae depicting the holy royal family on altars in their homes.

I appreciate that the Darnells hid this answer in plain sight: the subtitle of the book, remember, is When Akhenaten and Nefertiti Were Gods on Earth. Hardly monotheistic!

It would be tempting to interpret this self-deification stuff as an authoritarian power grab. The Darnells don’t think so. Instead they view Akhenaten’s religious reforms as the logical continuation of his father’s reign. Amunhotep III had presented himself as the sun god (recall the business with the Day Bark and Night Bark), and Akhenaten simply built on this with some theological innovations. One of these innovations is that Aten was said to be responsible for all of creation, and even that the present was the time of creation. This would explain the quasi-monotheism: all the other gods must be ignored, since in the Atenist worldview they didn’t exist yet. Only Akhenaten and Nefertiti were there, son and daughter of the Sun Disk at the beginning of the world.

Or something. These theological matters are confusing, and ultimately they’re just a bunch of educated guesses by John and Colleen Darnell and the researchers they cite. Besides, it’s not as if theology was strictly required to make a lot of sense, or to be separate from matters of secular power. There may not be evidence that Atenism was a pretext for a power grab, but the Darnells fail to convince me that it wasn’t.

What we do know is that several years into his reign, Akhenaten became more radical. He changed the complicated version of Aten’s name to remove references to other gods. It used to be “Re-Horus of the Horizon in his name of light who is in the sun disk”; it became “Living one, Re, ruler of the two horizons, who rejoices in the horizon in his name of Re, the father, who has returned as the sun disk”, taking out Horus (the falcon god) and light, in Egyptian shu, because this word sounds the same as the god Shu. At the same time, he ordered workers all over Egypt to hack out specific words from inscriptions in temples and monuments: anything mentioning gods, plural, and especially anything having to do with Amun. However, most other gods (Osiris, Ptah, etc.) were not affected.

We don’t have a direct explanation of why he did this, and I’m not sure I understand how the Darnells square his attack on Amun with “logically extending” the actions of Amunhotep III, for whom Amun was obviously super important. He may have believed that preemptively erasing the rival god would ensure the cult of Aten would be maintained after his death. If so, he failed spectacularly.

𓏿.

After seventeen years as the pharaoh of Egypt, Akhenaten died. We don’t know from what. He would have been about thirty years old, assuming he became king as a young teenager. Nefertiti may have survived him and reigned as the mysterious Pharaoh Neferneferuaten, or she may have died around the same time as her husband.

As mentioned earlier, Akhenaten had a couple of successors (Smenkhkare and Neferneferuaten) with short reigns and unclear identities in what was likely a troubled period. Eventually Tutankhaten/Tutankhamun came to the throne, which by the way was an elaborately decorated gilded throne, complete with Aten showering him and his wife with rays of gold —

— and after spending a few years in Akhet-Aten, he moved back to Waset. He (or more likely his advisors, since he was very young) then embarked on a program to restore the pre-Aten religion. A stela erected at Karnak during Tutankhamun’s reign positively lambastes Akhenaten:

The temples of the gods and goddesses beginning in Elephantine and ending at the marshes of the Delta [. . .] had fallen into ruin. Their shrines had fallen into decay, turning into mounds, overgrown with weeds . . . The land was in distress, and the gods ignored this land.

And so on about how the armies failed and the gods, when invoked for counsel, didn’t respond. Meanwhile, Tutankhamun claimed to have restored the Karnak temples to surpass even “what was done since the time of the ancestors.”

The Darnells are skeptical. They point out that even Akhenaten’s own tomb builders kept worshiping other gods beside Aten. In fact, we don’t really have any evidence that Akhenaten’s theology affected normal people who weren’t courtiers or priests of Amun. The cult of most gods likely continued unimpeded between Elephantine in the south and “the marshes of the Delta” in the north. Tutankhamun’s proclamation was probably an exaggeration, based on true events, but primarily meant to brag.

Still, it’s clear that Akhenaten, usurper of divinity and enemy of Amun, had become unpopular. His face was hacked out from most portraits and from his sarcophagus. His temples at Karnak were entirely dismantled. His city of the Horizon of Aten was abandoned and fell into ruin. Later, he was, together with Nefertiti and his successors including Tutankhamun and Ay, condemned to oblivion and removed from king lists. They’d be re-added only in the late 1800s AD, more than three thousand years later, when the city of Akhet-Aten was rediscovered.

As for Aten, his cult seemingly vanished and he became just a regular attribute of solar deities again.

𓐀.

Why does the Sun not play a larger role in religion? I don’t know. It certainly played a huge role in ancient Egyptian religion, and not just during Akhenaten’s reign.

It would have been cool to be able to say, “The radical worship of a solar god during the Amarna period heresy stood as a warning for centuries, even subtly influencing Greco-Roman religion and ultimately Christianity so as to deemphasize the all-too-obvious power of the sun.” I would have loved to find evidence, even thin, for an insight like that. But, as I rapidly realized while reading Egypt’s Golden Couple, it would have been a wild, unsupported extrapolation, on par with Freud’s theories around Akhenaten’s Oedipal complex and Moses as an Atenist, or with the idea that Akhenaten was a “scientist” because he recognized that the sun causes plants to grow and rain to fall.

The truth is, Atenism probably had very little impact on anything. And if it did, we have zero evidence for it. Many researchers have tried to find a link between this religion and the rise of monotheism in ancient Israel; a popular strategy is to compare the Great Hymn to Aten with Psalm 104 in the Hebrew Bible. But while there are some intriguing similarities, the scholarly consensus is that it’s all a coincidence. The cult of Aten was likely forgotten within a few generations, and wouldn’t have influenced any Jewish prophets.

You don’t win a book review contest by just summarizing some book — you need to use the book as a springboard to make some mind-blowing observation on society. This is doubly true of a book about ancient historical characters. Why would anyone care about Akhenaten and Nefertiti, if their story doesn’t provide any new insights?

I don’t have a great answer. The most I can offer is an epistemic warning. When studying a topic from ancient history — or anything really, but it’s particularly salient with ancient history because of the paucity of sources — it’s always tempting to speculate. And the wilder the speculation (Moses as a priest of Aten! Akhenaten as a totalitarian forerunner to Kim Jong-un!), the greater the temptation. We have to resist this. Don’t be like Freud!

To their credit, and despite (or because of?) their love of flashy vintage clothes, John and Colleen Darnell do a good job of resisting the temptation. Time and time again they demolish exaggerated claims about Akhenaten and Nefertiti, such as the idea that they were fighting a corrupt priesthood, the genetic defects the pharaoh supposedly suffered from, or the alleged sexual relations between him and one of his daughters. (It’s worth pointing out that they’re not always in agreement with the scholarly consensus, e.g. on the parentage of Tutankhamun or the identity of Pharaoh Neferneferuaten.) Occasionally you even get the sense that they’re going a bit too far — that they gave themselves the mission of defending two historical characters they love, denying any suggestion that Akhenaten and Nefertiti were bad people, which they may well have been.

Overall, the Darnells’ commitment to nuanced interpretation is great, but it comes at a cost: their book is less exciting, and more confusing, than I had hoped for. It doesn’t — it can’t — weave a biographical narrative that is coherent and compelling while remaining accurate. They try to salvage it by adding, at the beginning of each of the 31 chapters, a vignette reconstructing a relevant scene as it might have happened, but it doesn’t work that well. It comes across as a series of disconnected short stories and facts whose unifying point is hard to make out.

But it was worth reading. The story of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, fragmentary though it is, provides fascinating texture to the early history of the world, even without retorting to wild speculation. It proves that religious controversy was occurring long before any of the modern dominant religions were a thing. And the Great Hymn to Aten almost made me want to worship the sun, too.

… Or maybe that was an effect of witnessing the total solar eclipse that traversed North America last April, while I was in the middle of reading the book. Speaking of which, another piece of speculation about Akhenaten is that he may have been influenced by the total eclipse of May 14, 1338 BC, whose area of totality included Akhet-Aten. Depending on the exact chronology of his life, that could have inspired his religion altogether, or perhaps more likely, his radicalization at the end of his reign. Or it could have led to the abandonment of the holy city.

Or none of the above! We have no evidence for any of this, other than a single tomb painting where Aten seems to wear jewelry (that’s how the Darnells see it; they don’t mention eclipses at all) but that some have interpreted, rather fancifully, as an obstruction of the rays that could be the moon.

We’ll never know. But I can’t resist pointing out that one of the upcoming total eclipses, scheduled for August 2, 2027, will cast its shadow over both Luxor and Amarna. It probably won’t reveal any new information about Akhenaten, his mummy won’t wake up or anything, but an eclipse over the birthplace of the most sun-obsessed religion in history certainly feels poetic.

If you choose to attend, though, be careful: every lion will come forth from his den, all serpents will bite, and the land will be in darkness in the manner of death. Fortunately, this will last only six minutes, and then Aten will fill the land with his dazzling perfection once again.

I kept reading Atheism instead of Atenism, it was a strange experience.

Thank you for the text and may the sun shine upon you! ☀️

Thanks for putting some flesh on the bones of a period in ancient Egyptian history that has always fascinated us. It certainly illuminated our own explorations of Luxor and the Valleys of the Kings and Nobles: https://open.substack.com/pub/marcoandsabrina/p/wonderful-things-luxor-and-the-valley?r=10ijux&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web