The Enduring Prestige of Belle Époque Institutions

How the turn-of-the-20th-century European golden age still matters 🏅

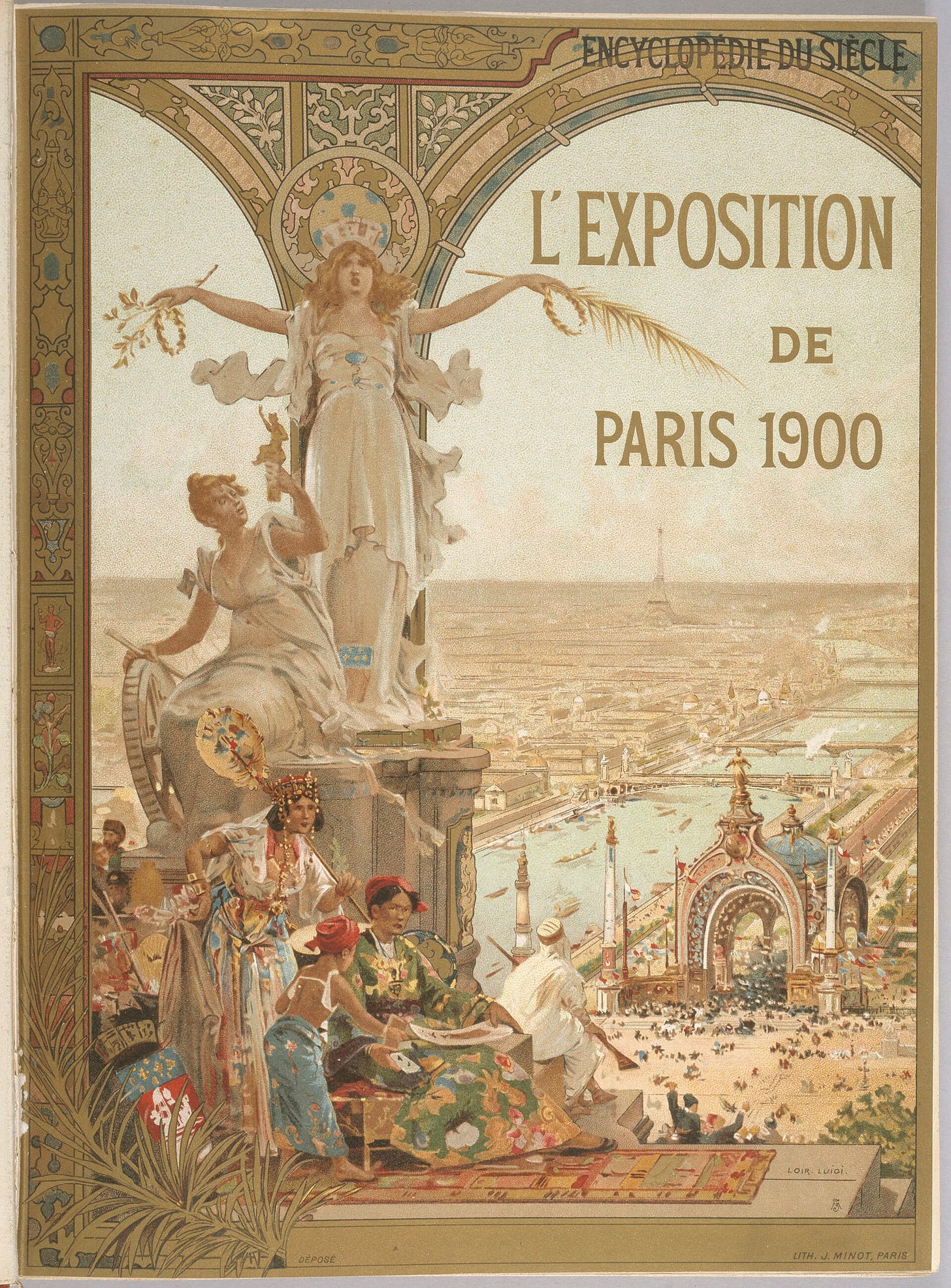

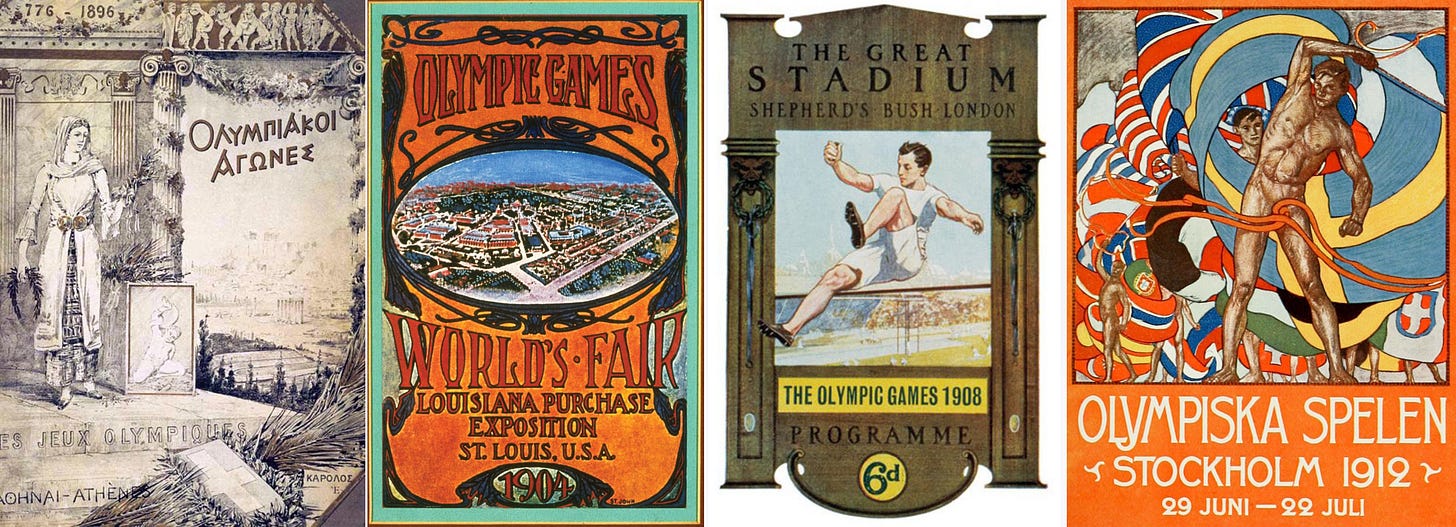

The Olympic Games, probably the most prestigious sports event of all, are going on in Paris as I write this, in 2024. The Olympic Games were also created in Paris, in 1894, at a congress convened by Pierre de Coubertin at the Sorbonne, which would evolve into the International Olympic Committee. The first games were held in Athens in 1896 and the second in Paris in 1900, during the Universal Exhibition.

In 1894 Paris was the center of the world, more or less tied with London. This was exactly twenty years before the First World War. The horrors of that war would prompt the inhabitants of France and Europe more generally to look back with nostalgia at the era at the turn of the century when life seemed easier and more carefree; they would call it the “Belle Époque,” the “beautiful era.”

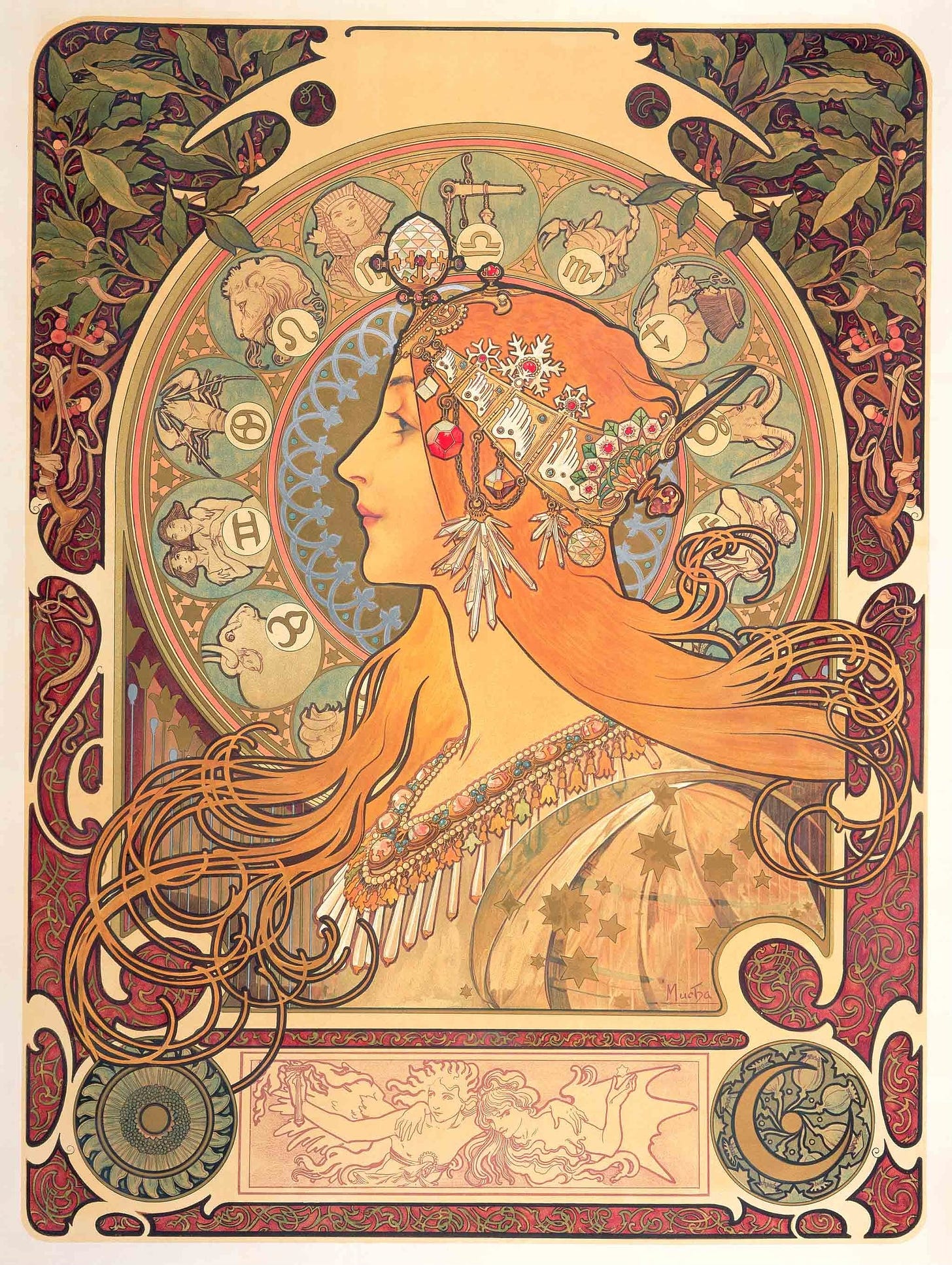

Today, the period starting at an indeterminate date in the late 19th century (let’s go with the mid-1880s) and ending in 1914 is remembered as a golden age of European and Western civilization.1 It was the height of Europe’s power over the world: the British Royal Navy commanded the oceans; Africa was almost entirely divided up among Britain, France, and other colonial powers; the formerly great cultures of India and China were under European domination and influence. It was a time of countless scientific and technological discoveries: the electron and the photon, radioactivity, automobiles, zeppelins, airplanes, cinema, the radio, early plastics, the diode and cathode-ray tubes, aspirin, the Haber process, Albert Einstein’s annus mirabilis, Marie Curie’s two Nobel Prizes. It was a period of intense aesthetic activity, including avant-garde artistic movements like Cubism and Italian Futurism, and especially the development of the popular (and still beloved today) Art Nouveau style, with its myriad incarnations across various countries, from the Secession in Austria, to Arts and Crafts and Modern Style in Britain, to modernisme in Catalonia, to Art Nouveau proper in Belgium and France.

It was also the time of founding of a surprisingly large number of international organizations that not only still exist, but are at the top of their league, in terms of prestige, influence, and reputation.

The Olympic Games is, in many ways, kinda weird. We don’t really notice the weirdness anymore because it’s been part of global culture for longer than anyone has been alive. But consider how the following features are quirky, and not at all required to hold a sports event:

Countries are the main competing unit, as opposed to individual athletes; as a result, the games are very political.

The event is held every four years in a different location.

The official language is French, and lip service is paid to this, though everything in practice is in English.

There are many rituals, like the passing of the Olympic flame, the opening and closing ceremonies, and medal ceremonies.

Some of the quirks of the Olympic Games come from its inspiration in the games of ancient Greece, such as the four-year schedule. But some others are clear products of the Belle Époque. The huge focus on countries is especially notable: the pre-WWI age was the heyday of nationalism, so it made perfect sense to stage a friendly competition between nations. The place given to the French language, despite the current dominance of English as the lingua franca of almost everything, is also a nod to the origin of the games, not only because they were the project of a Frenchman, but also because French was by far the most important language in diplomacy and international relations at the time.

It turns out the Olympic Games are far from being the only prestigious sports event with roots in the Belle Époque, with the quirks that this implies.

There is only one event that can claim to rival it in terms of popularity and prestige: the FIFA World Cup. The tournament itself is not exactly a Belle Époque event: the first one was held in 1930 in Uruguay. But in other other ways it totally is. First, the FIFA was created in 1904, in Paris (and note that FIFA is a French acronym, for Fédération internationale de football association). Second, the tournament grew out of the football events at the Olympics in the early 20th century, and adopted some of the Olympics Games’ characteristics, like the 4-year recurrence and the idea of competing nations.

Football (or soccer) itself is older, of course, and English: its modern form dates from the mid-19th century, and there were obviously lots of precursors. But its systematization into an international competition that would later grow immensely in prestige is very similar to that of the Olympic Games, and seems in line with the ideals of the Belle Époque.

The story behind many of the world’s high-status sport events and international organizations happens to be similar:

🚴♂️ The Tour de France, the most prestigious cycling event, was created in 1903.

🎾 Tennis, itself a glamorous sport, dates from a bit earlier, evolving into its modern form in the 1870s. So does the most prestigious of its tournaments, Wimbledon (1877). But two of the four Gland Slam events were created in the right period: the French Open (1891) and the Australian Open (1905). The other one, the US Open, comes just slightly earlier (1881). And the premier team event, the Davis Cup, dates from 1900.

⛳️ Golf, another glamorous game, has a less clear but somewhat similar pattern, with its Open Championship existing since 1860, while one of its four major tournaments, the U.S. Open, dates from 1895. (The other two date from 1916 and 1934.)

🚗 The Fédération internationale de l'automobile (FIA), which oversees car racing, was founded in 1904 in Paris.

🏊♂️ World Aquatics, known before 2022 as the Fédération internationale de natation (FINA), was formed in 1908 in London (right after the London Olympics).

🏃♀️ World Athletics was created in 1912 in Stockholm (right after the Stockholm Olympics).

⚾️ Major League Baseball is a merger of two leagues, one of which camer earlier (1876) but the other of which is a clear Belle Époque child, the American League of 1901.

Am I cherry-picking? Sure. But there really do seem to be fewer cherries to be picked outside of the Belle Époque time frame. Of course, plenty of leagues and tournaments were created more recently2 (and a few are older3), but I don’t think any combination of them comes close to the international prestige of everything I’ve mentioned so far.

If this pattern were just about sports it would be, at best, interesting trivia. But prestigious Belle Époque institutions cast a much wider net.

The institution from that time whose prestige has grown the most has to be one that I briefly mentioned earlier: the Nobel Prizes. They were first awarded in 1901, according to the last will and testament of Swedish inventor and industrialist Alfred Nobel (1833-1896). They are widely considered today to be the highest awards in the fields they cover: literature, physics, chemistry, medicine, and international relations.4 In fact, that last one, the Nobel Peace Prize, has been called “the world’s most prestigious prize,” bar none.

From the same era come a number of other distinguished awards:

The Pulitzer Prizes, awarded for journalism, literature, and music, were first given a bit later than the Belle Époque, in 1917,5 but should arguably count because they were conceived by the New York publisher and politician Joseph Pulitzer in his will before his death in 1911.

In France, the Goncourt Prize is the most prestigious literary award; it was established in 1902.

In the same year, Cecil Rhodes created the Rhodes Scholarship for graduate students to attend Oxford University. It’s probably still the most prestigious scholarship.

The Michelin Guide has become the premier system to rate high-end restaurants. That started in 1926, but the guide itself was first published in 1900 by the Michelin tire company as a way to encourage the few people who had cars to go places.

Then there are miscellaneous organizations that are still well-known today. The National Geographic Society and its magazine, National Geographic, began in 1888. The international Boy Scouts were created by Robert Baden-Powell in England in 1907. Esperanto, the most successful movement to promote a constructed language, was invented in 1887.

The period also saw the birth of some leading educational and research institutions (Institut Pasteur 1887, University of Chicago 1890, Stanford University 1891, London School of Economics 1895, Juilliard School 1905), though in this particular category the most prestigious ones seem far older and I don’t think there was any particularly high rate of new universities during the Belle Époque.

Does all of this mean anything?

I decided to write this post because it struck me that the Olympic Games and the Nobel Prizes, both among the most well-known and prestigious international institutions in the world, were created around the same period. Then I dug some more and found the rest of the examples in the post. It was more than I expected.

Of course, plenty of prestigious institutions don’t fit this pattern. Like I said, prestigious universities are usually older — many all the way to the Middle Ages, like Oxford and the Sorbonne. Prestigious scholarly societies like the Royal Society or the Académie française date from the 17th century. The most prestigious scientific journals, Nature and Science, date from just a tad earlier than the Belle Époque, in 1869 and 1880 respectively.

Many of the Belle Époque institutions are international in nature. But the most influential organization in this category is certainly the United Nations, founded in the postwar period in 1945. Its immediate predecessor, the League of Nations, was created in 1920. We do find a Belle Époque precursor in the Permanent Court of Arbitration, founded in The Hague in 1899 at the suggestion of Czar Nicholas II. But then we can also go earlier, to 1863, when the International Committee of the Red Cross was formed as perhaps the first international NGO to achieve prominence.

And though the Belle Époque saw a flourishing of prestigious awards being created, many others came later, like the Academy Awards in cinema (1929), the Fields Medal in math (1936), the Grammy Awards in music (1959), the Turing Award in computer science (1966), or the Pritzker Architecture Prize (1979).

All that said, I think it’s correct that the Belle Époque was an especially productive period for institutions that would become prestigious. Note the word “become”: most of the examples I’ve cited weren’t that prestigious during the Belle Époque. Prestige usually takes time to mature; newly founded institutions don’t have much of it, unless they are able to piggyback on the reputation of an already existing prestigious one. The Olympic Games were at first a minor event that was part of World’s Fairs or Universal Exhibitions, which were the prestigious international event at the time (and are unsurprisingly older, dating from 1851 or even the 1790s depending on how we define them).

If the Belle Époque is truly special with respect to founding institutions that would become prestigious, then we have two questions to ask. 1) Why? 2) What can we learn from it?

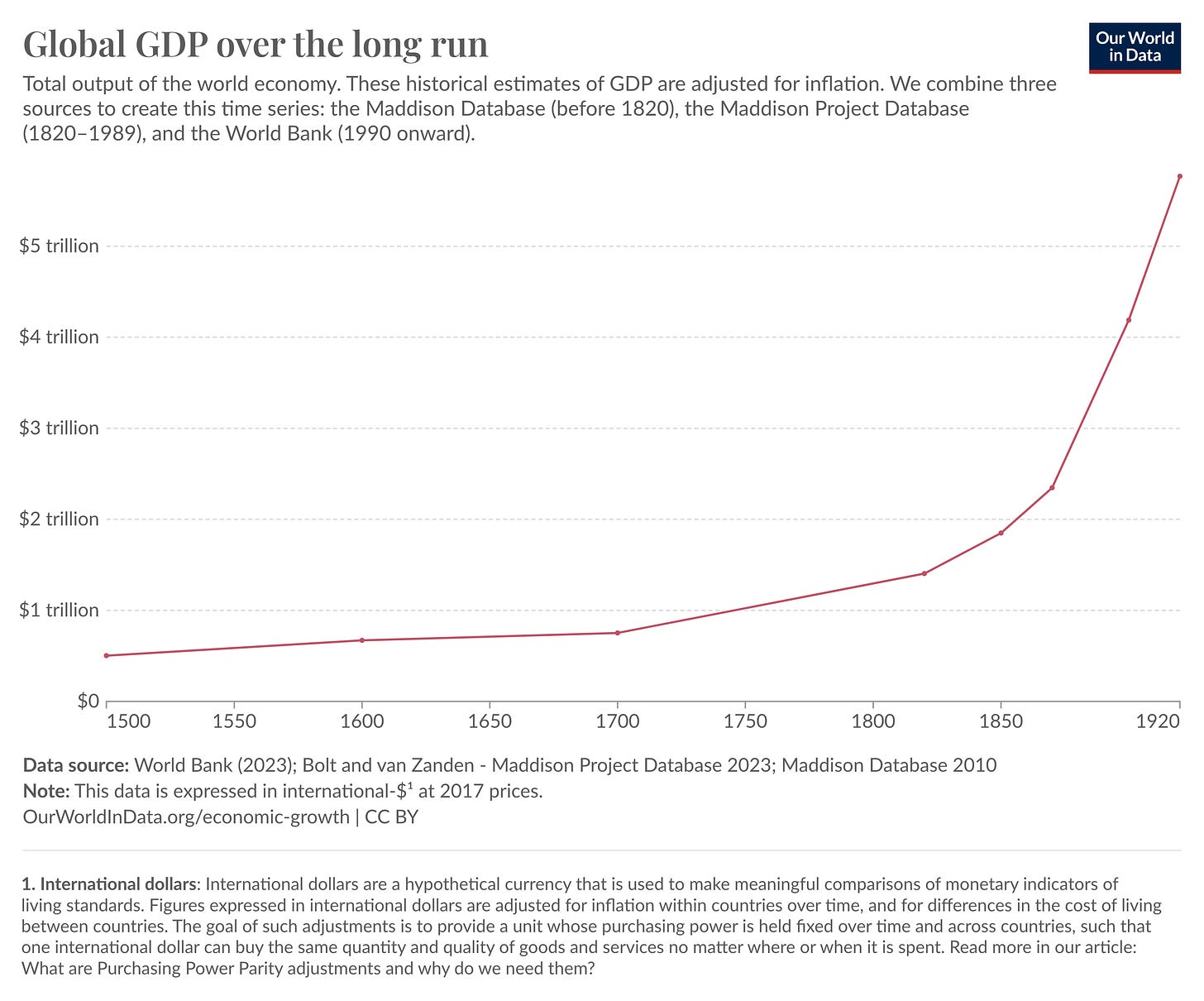

For “why?”, the first obvious answer is that the Belle Époque is distant enough that its new institutions had time to accumulate prestige. But they did that to a greater extent than the institutions from earlier periods with comparable timeframes, so we need a second answer, which is that “the time was right,” somehow. I think the time was right because the Industrial Revolution, towards the end of the 19th century, was finally running at full throttle. For the first time, compounding economic growth made society — or at least, the upper echelons of the most industrialized countries — wealthy enough to care about things like sports tournaments, scientific research, and literary prizes. There also began to be sufficiently many industrialized countries for international movements to make sense.

The political situation in Europe was also more stable, with France having had its Third Republic for a while, Germany and Italy being unified, and the UK still going strong under Queen Victoria. The perturbations of the 1840s and the Napoleonic era were a distant memory; the Franco-Prussian war was over. There was a lot of room for artists, scientists, and statesmen to work for the betterment of aesthetics, knowledge, and international cooperation. Plus, new technologies opened up possibilities. Long-distance travel was becoming economical, making a worldwide conference of athletes like the Olympic Games doable. Cars were being commercialized, allowing the creation of new associations devoted to motorists and racers. There seems to have been a widespread aesthetic of progress,6 and a (perhaps naïve) trust that innovation was going to make life better and improve morals.

The lesson from the Belle Époque, then, seems to be that… well, that economic growth is good, including for influencing the future. Long-lasting, reputable institutions are born at a higher rate when your society is wealthy, when it invents new things, and when international coordination manages to avoid war. This isn’t a particularly groundbreaking revelation.

But it might be good to take some time to realize it fully, now and then. The Belle Époque was, perhaps, the most golden golden age of Europe and the West. Demographic and economic constraints had never been evaded to that degree before, allowing the blooming of a wealth of great art, great science, a rising standard of living, new games, and prestigious organizations. Of course, the European civilization of the time got some important things wrong: its colonial rule over much of the world was stifling other cultures, and its intense nationalism led directly to the horrific First World War and the start of a century of relative decline. But for the 20 or 30 years it lasted, the Belle Époque really did produce great things that still matter a lot today, in ways that earlier and later periods didn’t. I think that’s a sign that economic growth, progress positivity, and great aesthetics are the best way to leave a civilizational legacy.

This post is mostly about Europe, which was still leading Western civilization at the time, but I’m also counting American achievements.

The 🏒 National Hockey League (NHL) was created just outside the time window, in 1917. The 🏈 National Football League (NFL) is 1920 (and the Super Bowl is 1966). The 🏀 National Basketball Association (NBA) is more recent, in 1946. All of these probably aren’t very prestigious outside of North America, though.

Like the 🐎 Kentucky Derby (1875).

Also economics, but that was added in 1969 so I’m not counting it.

Although, arguably, the periodization ending in 1914 makes less sense in the United States, which didn’t enter the First World War until 1917. The Panama-Pacific Exposition of 1915 in San Francisco seems very much to belong to the same era:

Note the focus on improvement of the traditional Olympic motto: “Citius, Altius, Fortius”; “Faster, Higher, Stronger.” Or the will of Alfred Nobel, which specifies the prizes have to be given to the people who confer the “greatest benefit on mankind.”

I think it is important to look at the philosophy of the time, neoclassicism, which extended beyond just the architecture. This was a very conscious revival or Aristotelian and heroic conceptions of virtue (the martial aspects of which arguably helped lead to WWI) and which championed a certain competitiveness and striving for excellence.

So it isn't too much of a surprise that institutions founded to promote the best of humanity and to cultivate excellence in themselves also tend to survive.

Fantastic work, thank you for putting it all together. Artworks really shine, too. I'm very fond of that period (not in a pseudo-nostalgic sense, but rather a potential study interest), in particular 1890-1900s, for it has... something in the air? if that makes sense (probably not haha). I even wrote an essay drawing some particular parallels between that age and ours, I can DM you if you're interested in reading it.