The Total Value of Art Stays Constant Over Time

AWM #99: There will always be a boundary between the mundane and the unknown to explore 🦬

Put yourself in the shoes (or whatever cavemen wore on their feet) of the first artist.

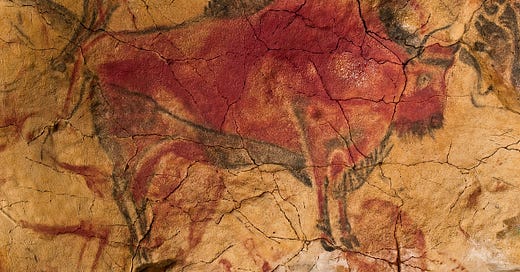

Nobody has ever made art before. Nobody has ever drawn a picture. In your hand there is a piece of charcoal from last night’s bonfire, and in front of you is the wall of rock of the cave you’ve been sleeping in. You notice that the charcoal leaves a trace on the rock. Huh, cool. You can make some shapes. Well, you don’t have a concept of shape, since you’ve never seen any abstract shape, just real objects, but that’s not going to stop you. You draw a line, and then a bunch of lines together, and then filled surfaces. This is fun.

After a while of messing up with the charcoal and the wall, you have a dramatic idea: you can actually make shapes that look like other things. Like your hand. Or trees. Or animals. You cover the wall with those “drawings,” and then you show it to other people in your tribe.

They’re impressed.

Why? You lack the philosophical theory to answer this, or even ask the question, but I can sketch a superficial answer. You drawings have elicited an aesthetic reaction. This means feelings similar to those that the cavemen get when they look at an appetizing, clean, fresh fruit; or a green landscape with abundant water; or a sexy and healthy potential mate. But while the feeling of beauty from these examples clearly arises from their ability to fulfill people’s needs, it’s less clear why your shapes made out of charcoal would do the same.

The deeper answer is that people are attracted to the drawings because the drawings are new; they’re something that nobody has ever seen before. And humans have a natural tendency to notice such things.

Definitions of art are plentiful and will be debated until the end of times, and I don’t necessarily want to spark such a discussion. Moreover, I fear that my definition may seem obvious to the point of insult. Still, I think that it’s the best way to think about what art is and what role it plays: art is just anything that is made to elicit beauty — i.e. to cause some kind of positive feeling while being interesting.

The cavemen above are positively impressed because the charcoal drawings are interesting. The drawings are interesting because they’re new, and also because they’re understandable. They organize information in a way that is both outside the usual, and not too far out. Imagine showing a Picasso to hunter-gatherers; it would make no sense to them.

In other words, art is interesting, and is therefore art, because it lies precisely on the boundary between the mundane and the unknown. The inevitable consequence is that what art even is changes as the boundary moves.

You’ve been enjoying a fulfilling career as a charcoal drawer. The tribe leader asked you to decorate the walls of the latest cave you’ve moved to, and people from other tribes have been visiting. Some kids asked you how you do it, and you’ve set up a kind of school to teach them the fundamentals. You don’t even need to hunt or gather anymore, since people bring you gifts all the time. You’ve made it as a full-time artist. The first in (pre)history.

One day, years later, you hear news of one of your ex-students, who had moved into another tribe after marrying a well-known hunter from there. Apparently that tribe extracts a red powder they call ochre from their cave, and your student has been adding some of it to her own charcoal drawings, making the pictures bichromatic. You’ve never heard of such a ludicrous thing. There’s plenty of color in nature; what makes the drawings valuable is that they represent the world with the purity of charcoal black. Why would you want to add red?!

The other cavemen have also never heard of such a thing. But to them it isn’t ludicrous — in fact they find it quite interesting! Combining colors allows for more expression and for more realistic detail. They ask your ex-student to decorate their walls, and she does, and she even visits your cave to make a new mural for the chief. As she does, she reveals a new innovation: trichromaticity, from adding yellow ochre to the palette of carbon black and red ochre. You throw your hands up with exasperation. Two colors, you could maybe accept, but three? This is getting ridiculous.

A friend points out that you’re bitter because you’re simply not the coolest person around anymore. You angrily tell him to shut up (what a bad friend!), but as you sulk, sitting with your back on a wall that you’ve just painted with an intricate pattern of carbon black leaves, you wonder if he may be right. Your art used to be popular because it was new, but now there’s something newer. Nothing has changed about your work; but something has changed in the surrounding culture. The boundary of the mundane has moved.

Nobody comes to admire you new fresco, or if they do, they aren’t as impressed as they used to be. Why is it monochrome black? It’s kind of boring. You realize that the value of your art doesn’t fully come from its physical properties; it mostly comes from the people who see it. They want to see new, interesting things. Having rare skills is a way to make interesting things, but it is not good enough on its own.

You wonder if you should pay a visit to your ex-student, and ask her to teach you.

The title of this post isn’t true in an absolute sense. The total value of art does increase over time. However, that’s because of forces that are external to art. Mostly population growth, really, as well as economic growth. Art (and I mean the sum of all of it, not any specific work or genre) is more valuable in an advanced world with 8 billion relatively rich people than in a prehistoric world with fewer than a million hunter-gatherers, simply because there are more people in the former, and they each have more free time to enjoy the many incarnations of art.

The claim, however, is true in a relative sense. If you control for population and wealth, the sum of all art will always have about the same total value. That’s simply a consequence of the boundary idea: although the circle it encloses can grow in size, and therefore increase the boundary’s length, the boundary’s thickness remains constant.

The easiest way to control for population and wealth is to consider a single person. What makes art interesting, to you? Many things, to be sure, since aesthetics are another of those insanely multidimensional things that we can only imperfectly visualize with 2D shapes like a circle. The art you like depends on what art you’ve been exposed to before, and on what field you work in, and on what others around you like, and on what your culture identifies as cool or prestigious, and so on.

But assuming constant wealth, and therefore constant free time and money, I think it’s true that the total value of all the art you consume doesn’t depend on what the art is. It doesn’t really matter if you spend your time & money “art budget” on film, TV, museums, novels, concerts, or video games — the total contribution of art to your well-being will be about the same. (We can complicate this simple model by considering the quality of the art you consume, but let’s just assume that whatever you choose to consume is what you’d enjoy the most at that time, so that your well-being is maximized.)

What makes your art budget allocation change? The discovery of new art — of stuff that is on the boundary between what is mundane and what is unknown (to you).

Now, unlike the cavemen in our example, who had access to no source of beauty outside of nature, we have enough existing art to spend a lifetime discovering things while ignoring anything created in our lifetimes, if we wish. And some people do that, refusing to read books younger than a hundred years old, or making it a core part of their identity to hate on modern architecture. But they, too, are attracted to novelty. It’s just that their own boundary line is shaped differently from that of people who like contemporary stuff.

In a dynamic culture, old art is constantly being displaced by new art. But people’s art budget remains the same overall. There’s only so much well-being that a person can get from art, and therefore, whenever something captures more interest, something else must decrease to compensate.

If we expand this model to the entire world, we reach the conclusion in the title: [assuming a constant population and wealth], the sum of the value of all art in the universe never changes. It’s a big zero-sum game, in which artists compete for everyone’s art budget allocation.

You and some of your other ex-students have gathered, tonight, in the great hall of another tribe’s cave. The place is fully decorated with charcoal drawings — there isn’t a single spot of ochre here. The area doesn’t produce any pigments, so the people of this tribe are still used to monochrome black art.

It’s interesting how the art world has split in two schools of roughly equal size. A “progressive” faction that wants to innovate in color use and style, and even do absurd things like paint abstract concepts. And a conservative faction that rejects any art that doesn’t follow the established norms of using charcoal and nothing else. It’s the first-ever quarrel of the Ancient and the Moderns.

You’ve been invited as the originator of the movement and the “old wise artist,” but in truth you don’t have much to say. You listen to your colleagues’ arguments. They claim that it would be unfair if new art always used ochre, since not everyone has access to rare pigments — unlike charcoal, which everyone has access to. They say that it would be inconsiderate to old artists who have perfected their skills in carbon black art. They say that if we don’t stop polychromatic art now, who knows what else will be invented later, making old artists increasingly irrelevant? In the long run, the damage to the artistic community could be irreparable!

A decision is made: polychromatic art should be rejected. Artists of the Charcoal School shall refuse to work in the new styles, or use any new pigments. They shall pressure tribe leaders to ban polychromatic art. They shall not associate with polychromatic artists.

As you watch in silence, you can’t shake the feeling that all of this will be for naught. Though you’re not happy about it (you’ve tried working with ochre and… meh, you’re not a fan), you know that polychromatic art will win, given enough time. It’ll steal whatever interestingness charcoal art still has. It seems inevitable.

Is this a post about AI art? Of course it’s a post about AI art.

My first impressions of AI art weren’t too positive. In an essay I wrote not long after DALLE•2 took everyone by storm, I tried to be nuanced and optimistic, but I did conclude that I was rather worried. Analogies with innovations of the past — most commonly, photography and its disruption of the visual arts — seemed overdone, not necessarily applicable to the current situation. AI art doesn’t really feel like “just a tool.” It does too much.

Now I’ve turned around somewhat. I still think AI art will rightfully anger a lot of artists. It’ll have a lot of impact at the individual level, like photography did. And it will be involved in a lot of fascinating legal battles, for instance over the use of intellectual property to train algorithms.

But overall it… won’t really change anything at the level of our civilization. There will still be a lot of art, like there was after photography (the analogy is pretty good after all). The art will be different, yes. But there will never not be art. There will never not be a boundary between the mundane and the unknown.

And that’s because the total value of art stays constant over time.

The usual implication of a “zero-sum game” is that no one can win without someone else losing. The reverse implication is that no one can lose without someone winning. Otherwise it would be a negative-sum game.

In other words, it’s impossible for something like AI art — or photography, or ochre pigments — to destroy the capacity of people to be interested by stuff. The job of the artist, then, is to figure out what can capture people’s interest. Fundamentally, that’s all that matters.

What does not fundamentally matter is the specific technical skills used to get there. Oh, having rare skills can be a great way to interest people, but there isn’t any inherent value to skills, if people stop being interested for whatever reason. Of course, this really sucks for anyone with such skills! If you’re a charcoal artist in the time of ochre,1 or a photorealist painter in the time of color photography, or a digital artist in the time of image synthesizers, then yes, sorry, the market value of your skills will suddenly become lower. It’s harsh, and you deserve sympathy and support.

Consolation may come from realizing that you probably also have certain skills that are more difficult to define, but are no less important than technical stuff. They are what we might call your creativity (or imagination) and your empathy — your capacity to figure out what people find interesting, to navigate the mundane-unknown boundary. Those skills will remain useful as long as humans are around.

It’s fine if you don’t like AI art, if you feel threatened, if you wish it didn’t exist. You can still do art the old way! You don’t need to do art primarily because it interests others. If you do want to target that boundary, however, then you have no choice but study what people want to see, and use your creativity and empathy to do so. There’s no reason to think you wouldn’t be able to.

The quarrel of the Charcoal School and the Ochre School has… not really panned out, actually.

The reason is that both schools have been infighting. The Charcoal people have been quarrelling over whether it’s acceptable to paint skin instead of just rock. Some Ochre artists invented a new pigment, a blue powder made out of lapis lazuli, and ironically many among the older guard of the Ochre movement really dislike it. Three colors was perfect, why would you need four?

So in the end, everyone’s just been doing their own thing. This is also true of you, the inventor of carbon black art. You’ve given up on the politics and the debates, and now you’re just exploring the further possibilities of your favorite medium, charcoal. You’re not as popular as you used to be, but that’s all right. Some people like the classic, vintage aesthetic of charcoal drawings. Some recognize your past reputation and still see a lot of value in your work. You’re getting by.

There are, after all, an immense number of ways to be interesting. You don’t need to compete with the whole world. Let the kids experiment with new techniques, and if they come up with new interesting work, all the better for them! You wouldn’t want young artists to just copy your first drawings forever, right? That wouldn’t be very interesting.

You put the finishing touch to a grand hunting scene, in which carbon black figures with spears are attacking carbon black aurochs and bison, and then you take a step back. Your finest work, perhaps. You wonder if people, years after your death, will still find it interesting. Maybe they will. Maybe they won’t. It doesn’t really matter. You like it, and that’s all you need.

Quick note to say that this is probably not an accurate model of how art appeared in real life.

What a well written and interesting post. I like your no colour vs. colour cavepainting analogy. I think it fits very well in this discussion about AI vs. human made art.

The charcoal/ochre art analogy is an interesting one, and I think you're mostly right about the global value of art remaining fairly constant. Businesses will still want to pay minimal amounts for corporate blog headers. Dentist offices will still buy the same hot-air balloon and beach photographs to put on the ceiling over the chair. Game companies will still pay professional artists to create textures and refined concept art.

However, there's also the personal connection that you sort of touch on just below the Prokudin-Gorsky painting. Imagine your well-off grandmother knit you a sweater for Christmas. It's not the best. It's sized kinda weird and the design isn't your style. But it came from grandma. You appreciate the time she devoted to making it, the little flaws that come from her old hands, and the out-of-fashion style that came from her time.

Two weeks later, you're looking at Macy's clearance section and see the same exact sweater (later confirmed when you notice the stub of a cut-off tag on your copy). The value you once had for the sweater is gone. The perceived time-value in making the sweater (or working to afford it if grandma was strapped for cash, but you know she has a new top-end Tesla) was an illusion. The flaws that were once part of the charm of being hand-made are now corner-cutting measures and faults of machine instead of man.

Passing by the legal and ethical issues of AI art's training sets, you still have the person behind the art and the connection you can get to them through it. I wrote something similar to palisatrium of the Short Story substack, and I'll repeat the short version here: Go to Yuumei's website[1] and you can immediately guess that she loves nature and cares about the environment. Go to her blog and you can confirm it based on her past fundraisers. You can see the person in the art - nuance included.

Contrast that with someone posting AI artwork. You can see what they like, but only at the same level as you can tell someone's favourite genre by looking at their Netflix history or their fashion sense based on what they buy at a department store. *At best*, they're limited by choice of what's presented to them[2]. *At average*, they're only saying "I thought this was pretty". *At worst*, they're lying if they claim they made the artwork themselves[3] and act as though they put great effort into it.

Again, I believe you are right that art has constant value. But I think that's true only for the aesthetic value. The humanist-interpersonal-connection value is empty.

[1] https://www.yuumeiart.com/

[2] There's probably some Wittgensteinian expansion that a picture is worth a thousand words, but who knows if those words mean the same thing.

[3] by not disclosing it was made by AI