All adventure video games (or, well, most, but it would have been a less catchy title) are set in winter. The logic is as follows.

In an adventure game, it’s common to have a number of regions with different characteristics, so that there is variety in the environment that the player traverses as they complete the main quest. Sometimes people call these “biomes.” There is often, somewhere on the game map, an ice or snow biome.

Snow biomes are inspired from real-world snowy landscapes, which people in temperate zones are usually familiar with. For example, here is a picture of a city park covered in snow that I took last December after a big snowfall.

As you surely notice, this picture contains a lot of trees and is rather pretty, though the photograph doesn’t come close to capturing the fairy-tale beauty of the entire city after that snowstorm. Snow, somehow, is very picturesque, and snow-covered trees feel magical.

Game designers usually try to create nice-looking environments in their games. When they design snow biomes, they usually try to create something more interesting than a barren ice-covered plain, or a barren ice-covered mountain. That is, they add trees.

Trees, of course, are plants. Plants require a number of environmental properties to thrive: light, air, liquid water, and a reasonable temperature to allow for chemical reactions in their cells. Some plants, including many kinds of trees, have evolved to survive the cold conditions of temperate winters — but they only survive them. They don’t thrive when it’s snowy outside. Every winter, trees just sit there, waiting until the start of the next growing season in the spring.

(This is, by the way, why trees have growth rings. The dark and light pattern indicates the alternance of waiting season and growth season.)

Some video games have a built-in season cycle. In these games, trees will be covered in snow, but only during the in-game winter season. Other games have some narrative justification for why it’s winter, such as an angry god who put a curse on the land so that it is forever cold — until the hero defeats the god and restores order to the world.

But most games don’t bother with seasons, and just have a biome that is always cold and snowy. They draw inspiration from real-world places that are permanently cold and snowy, like polar regions, or the top of tall mountains …

… except that these places never have trees. Since they never have a season warm enough for plants to grow.

Also note that permanently cold regions never have any cities, except for unusual research stations like Amundsen–Scott. Would you live in a place that had an eternal winter? Neither would anyone else. Which doesn’t stop video game designers from putting picturesque snow-themed villages in their games.

The only conclusion from all of this is that most games, at least those that have a snow biome but no in-built season mechanic, should be understood to be set in winter. Most regions of the game map have a warm enough climate to look like summer, but in the colder areas, the trees and villages are covered in snow, for the aesthetic delight of players.

It is not an error to set a video game during winter, but the fact that it happens again and again suggests that it is rarely a conscious decision. Rather, it is one of many cases where people just go by the clichés.

Collecting such situations is my hobby. I once wrote about the phases of the moon, and how people will easily create totally unrealistic situations in their stories, art, and games, just because they gave exactly zero thought to how the moon works. The cliché states that the moon appears at night, so they’ll have a crescent moon rise at sundown, even though crescent moons can only rise around either 3 AM or 9 AM.

To stay in the realm of game environment design, another one I like is about deserts. What comes to mind when you think of deserts? Sand dunes? Camels? Tall saguaro cacti? Egyptian pyramids?

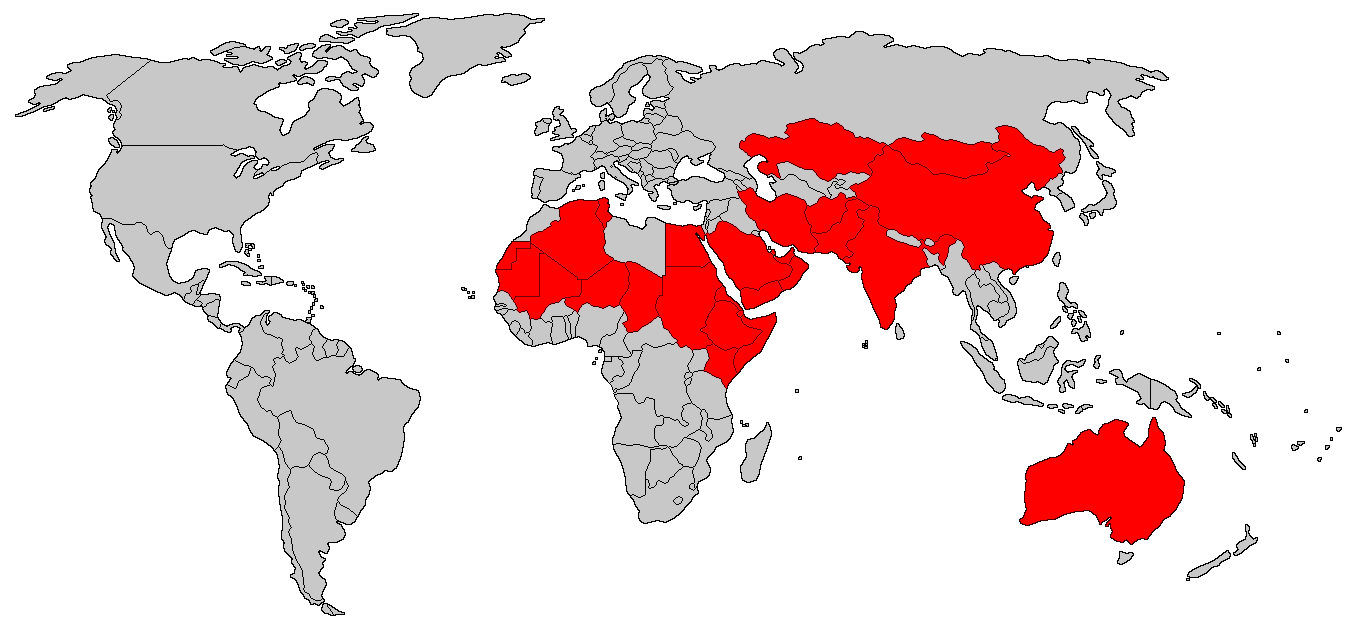

But sand dunes are actually relatively rare, and occur just in a few areas of the world’s deserts. Egyptian pyramids, of course, occur only in Egypt (and Sudan if you count the Nubian pyramids). As for camels and cacti, consider their respective ranges:

Just like in the case of snowy trees, you can invent all sorts of justifications for a desert that has both camels and cacti. Maybe your story is set in the postapocalyptic future where a domesticated North American camel population has gone feral. Maybe your story isn’t set on Earth at all, and these aren’t camels or cacti, but just similar-looking alien organisms. It’s even fine to say you don’t care whatsoever about ecological realism. But it is slightly better if you somehow communicate that you don’t care, instead of looking like you’ve never even thought about this.1

Yet another example is river bifurcation. In real life, rivers very rarely split into multiple ones that don’t rejoin later. When bifurcation occurs, it’s usually close to the sea, in delta areas. There are sufficiently few natural examples of rivers splitting far inland that Wikipedia has a fairly comprehensive list, and that the Casiquiare river, a natural canal that joins together the river systems of both the Amazon and the Orinoco in South America, is considered “exceptional” and “unique.”

The cliché is that rivers form branching patterns, as the Amazon basin in the above map clearly shows. But few people stop to think that this branching is almost always smaller rivers joining into a larger one, instead of the opposite, and so we get games like Animal Crossing where you can choose from dozens of island layouts, every single one of which is hydrologically improbable.

Why do I care about this? Games are almost never meant to be fully realistic. They’re set in fantasy worlds, where for all we know rivers bifurcate all the time and trees grow fine even when they’re covered in snow 365 days a year.

One reason I care is that I am an insufferable nerd, and I like to pay attention to detail. This whole post, of course, is an exercise in pedantry. I won’t be mad if you ignore all my advice.

The other reason I care is that this is a good illustration of how creators are so often limited by their imaginations. The real universe is complex, so have no choice but to simplify it greatly, all the time. One of the ways we do that is clichés, which are essentially pre-packaged bundles of ideas. Pre-packaged ideas are extremely useful to gain speed and serve as building blocks to think deeper thoughts, but they do have downsides. They’re less interesting, because they tend to be used often. And they contain mistakes, which you won’t notice until you open the package and look inside.

Clichés are also self-reinforcing. Each time you see a snow biome with snowy trees, it makes you expect snow biomes in future games to also involve snowy trees. In a world where not that many people experience an actual permanently cold area, or an actual desert, or actually take the time to observe the moon and understand its cycle, then the cliché can become all that we have.

I opened this post with a painting from Ivan Shishkin, an artist whose work I find fascinating because it comes extremely close to photographic realism a few decades before color photography became widespread. It was fitting to pick a winter forest landscape, considering the topic. But I worry that this will reinforce the idea that Russia, a very northern country, is always covered in snow — an idea that is obviously false, but somehow gets a lot of mileage anyway. (Canada, where I live, gets this a lot too.)

I was going to close with another wintery painting by Shishkin that I find beautiful, In the wild north…. But the vast majority of his works depict forests during other seasons — snowy landscapes are only something like 5 paintings out of about 200!

So, in an effort to undo the cliché, let’s end by saying that the Russian Empire towards the end of the 19th century, although it sometimes looked icy and cold, also at times looked like this.

There is of course a TV trope page about how All Deserts Have Cacti.

When I put a moon in a story, I always double-check to ensure its phase aligns with the time of the day, season and whatnot. I've always wondered whether any readers thought of this.

This was such an enlightening post. I look forward to many more!