How do we humans know what’s good and what isn’t?

You’ll forgive me for being annoyingly unspecific: I am deliberately asking this question for any thing, with the most general definition of good you can think of. How do we decide whether a meal, a work of art, a behavior, a person, a political idea, a story, a mathematical equation, an arrangement of objects in space, or a kind of weather, is good?

And how do we decide in ways that agree with most of our fellow humans?

One answer, perhaps the “ideal” one, is intellectual theories, or explanations. Ethical goodness, for instance, is typically analyzed with the frame of theories like utilitarianism, deontology, or virtue ethics. By looking at consequences, rules, or virtues, we can collectively decide whether a given action is good or not. But let’s be honest here. Most people don’t know any of these theories; yet everyone is able to recognize goodness anyway. Plus, the theories all fail in various corner cases, which is one reason there are three main theories (and some smaller ones) — not a very promising sign for explaining why and where we agree.

Besides, I am interested in how we determine goodness in practice, including in the common situations where we must pass judgment quickly, with no time to figure out a valid explanation.

Another answer is through memes. We’re cultural beings, so we look at what our culture says. It can be as simple as trusting the judgment of someone we know, in a kind of two-person culture: if your spouse liked this book, then the book is probably good (at least enough to try reading it). Memes are also embodied in much larger cultural units, like families, language groups, countries, and religions. When evaluating the goodness of a thing, we may ask, more or less consciously: “does my culture think it’s good?” We’re more likely to like the thing if we believe a culture we belong to likes it, thus generating agreement.

But cultures can be wrong; that’s why there’s such as thing as moral progress. And there are plenty of new things to evaluate for which our cultures have no answer, or for which the different culture we belong with disagree.

Yet another answer is pure physical pleasure. What’s good is what makes you feel good. It sounds circular, but “feeling good” can reasonably be defined as physical states in which we prefer to be. This answer is pretty close: in practice, most of the time, pleasure-based judgments work well. Food that smells disgusting is less good that food that smells nice. Plus, because of our shared biology, humans tend to agree a lot. But it’s not hard to think of counterexamples. If we relied only on physical sensations as a guide, exercise would seem bad, since in most cases it makes us feel physically worse, at least at first. Likewise for foods that are described as “an acquired taste.”

There are also a lot of things that don’t really cause physical pleasure one way or another, except, indirectly, through the intellect. Why can a sad breakup story be “good”? What about a work of art depicting violence? John Stuart Mill wrote of higher and lower pleasures: simple sensory pleasures don’t quite make us happy. From here we could go back to our first answer, intellectual theories. We certainly use those as a complement to pure pleasure: we might have, for example, a theory that exercise is good for us in the long run even if it makes us feel breathless, sweaty, and generally miserable right now.

But instead let’s bring up a fourth answer, the one that combines intellect, physical sensation, and intuition: beauty.

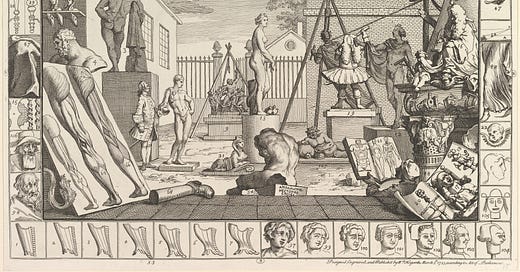

Beauty is complicated enough to have its own branch of philosophy studying it (aesthetics), not to mention millions of artists who puzzle over it even as they try to find and create it. So I won’t try to define it. But I will say this: I think it is, most of all, a heuristic.

Goodness, obviously, is multifaceted and complex. There is no single way to determine it. At some point in the evolution that has made us into conscious beings, we developed the capacity to feel pleasure, and that was useful, because we (we were probably, then, sea animals swimming in the oceans of the Paleozoic era) could more easily float towards the good things we needed to survive. But this wasn’t quite enough, so we eventually developed the capacity to come up with explanations. As primitive animals with limited intelligence in a complex world, however, our explanations were rarely adequate. Later, a workaround would be culture: once an explanation had been made by another being we trust, we could simply use it for ourselves. But in the meantime, nature needed to give us something more practical. A heuristic that we could generally apply to any area of life and get an acceptable result to complement physical pleasure. Nature gave us the perception of beauty.

Our perception of beauty doesn’t work any more perfectly than the other methods. Sometimes we’re repulsed by things that later turn out, after some theorizing or cultural influence, to be quite good. Other times we fail to see the badness of things that superficially appear beautiful.

But beauty is often the best bet we have, especially when explanations elude us. It is approximately as general as goodness itself. It takes into account physical pleasure as well as culture, and memories of both. It is modifiable by the theories we come up with. We may find a fresh salad beautiful because we know a similar instance of it has provided us with physical pleasure in the past; or because people we trust tell us it’ll be delicious; or because we have a theory that eating salad is good for our health; or some mix of all three.

Despite beauty being obviously subjective to a degree, since it depends on our own memories, influences, and explanations, humans have a surprising level of agreement about it. It’s common for sufficiently many people to agree that a work of art is beautiful enough to put in a museum or award it with a prize. Indeed, art couldn’t exist at all if beauty wasn’t mostly aligned across humans.

In fact it works across species, too. Flowers are attractive to both humans and pollinator insects. It is possible that this is a coincidence, but it would be a surprising one. The more likely explanation is that plants, faced with the problem of needing to communicate something to living beings very different from themselves, figured out some universal truths about beauty, like the fact that symmetry and contrast are good ways to attract attention.

Artificial intelligence could be described as one or more new species. They are alien minds, totally distinct from how our biological minds work. So when we worry about AI alignment, the problem of making sure the AIs are in agreement with humans as to what is good and what should be done, I can’t help but think that there’s a precedent for it. It sounds corny, but maybe we should take seriously the idea that alignment will be solved by teaching AI to see beauty?

I’ve had this post in my drafts for more than a year and a half, under the title “Beauty Is the Original Solution to the Alignment Problem”. A one letter difference with the current title, in the second word.

Worse than that: it was, uncharacteristically for me, a handwritten draft. Dated January 23rd, 2023. Eighty-three posts ago. At the time I had thought of this essay as… some sort of conclusion, a crowning achievement of my amateur research into aesthetics. It would be speculative, but tantalizing. However, I felt I didn’t yet have what it takes to write more than a quick, poorly handwritten draft. I would let it simmer for a while and then come back to it.

I have never wanted to, until now. Big ambitious crowning achievements tend to be like that. They’re daunting, so you put them off forever.

The above post isn’t quite the same as my handwritten version, but I didn’t change the structure or the main argument. I told myself I’d get further by just getting it out of my system, whatever flaws it may have.

So how much do I believe that beauty could be the a solution to the alignment problem?

I suppose it at least merits further exploration. Our perception of beauty has some neural basis, which means it must be possible to somehow encode it into an artificial neural network. But the way we encode things into artificial neural networks is by feeding them huge amounts of data and performing gradient descent. Can we teach them beauty by doing this? I have no idea, and I’m not aware of anyone who has seriously tried.

To be sure, there’s been some thinking around aesthetics in the field of image generation. For example there’s the LAION-Aesthetics dataset, containing only images that were deemed as having “high visual quality.” That’s a start, and I think image generation AIs have learned some dimensions of beauty thanks to such approaches, allowing them to create mostly images that humans would consider beautiful. But my guess is that this is only a fraction of what a full specification of beauty would be. For one thing, beauty is far more general than just images. For another, it is changing, and there’s a risk that whatever an AI has learned stops being true at some point. To the extent that AI-generated images have a discernible style, I think that’s already happening: recognizably AI-made images are less beautiful. So we haven’t fully taught them beauty yet.

Maybe the perception of beauty is an emergent phenomenon, and it’s not really possible to add it to a system. In this view, nature or evolution didn’t give it to us; it just naturally arose as a consequence of having a sensory system, an intellect, and the capacity to make judgments of goodness. It would then be pointless to try to reproduce it. Just train AIs to do whatever, and if it helps it to develop aesthetic taste, then it will. I don’t know.

Even supposing that we could teach beauty to artificial intelligences, would it actually help with the alignment problem?

I doubt it would solve it completely, in the way I doubt the problem is soluble without solving all of moral philosophy. But aesthetics feels… easier, in a sense? I tend to view it as a sandbox version of morality: similar, but the stakes are much lower, and it’s easier to run tests. So maybe it’d be worth trying to fully specify the perception of beauty before we dare try to encode all of morality into them. Whether we succeed or fail, that’ll be useful information for when we truly need AIs to be morally aligned with us.

We should probably, at the same time, code our AIs to come up with explanations, take into account the opinions of others and of cultures, and (maybe, for robots) feel pleasant physical sensations. But there’s a reason we were endowed with the capacity to perceive beauty, and my guess is that we should take every route we can for our artificial alien minds to agree with us about what is good and what isn’t.

Did you ever see this nice essay "A Natural History of Beauty" https://meltingasphalt.com/a-natural-history-of-beauty? It's about how beauty might evolve as a repeated multiplayer game.

Your idea reminds me of that framework! Especially when you mentioned the symmetry of flowers.

Would such a project allow for finding even Socrates beautiful, as Alcibiades - by then filled with love for him - eventually did? What about, as Marcus Aurelius wrote, seeing the beauty in such things as the broken top of a bread loaf, or 'ears of wheat bowing down to the ground, a lion's wrinkled brow, a boar foaming at the mouth...the gaping jaws of wild beasts,' and old people, which, he argues will only be seen and appreciated by a sensitive person (Meditations 3.2)? Can AI be trained to recognise beauty, if it doesn't feel love?