A confession: I’ve had this half-written (okay, more like 30%-written) article in my drafts for more than two years. I just checked, and I apparently created it in November 2021. I am impulsively publishing it now, because otherwise I never will.1

To be clear, this is an admission of defeat. I don’t know how expensive architectural ornamentation is. I don’t know, and apparently neither does anyone else. Decorative architectural elements are one of the highest mysteries of the universe, not meant for mere mortals to ponder.

At the crux of the problem is the fact that there are two equally plausible, yet mutually exclusive explanations.

One the one hand, detailed ornamentation clearly costs so much, for benefits that are at most unclear, that the correct economic decision is almost always to give it up in order to save money. Governments can’t justify commissioning a sculptor to add a beautiful frieze to their public buildings. People can’t justify paying extra to both an architect and a general contractor just to add a fancy cornice on the roof of their house. When some people did this anyway in the past, it was because labor was cheap enough to make it affordable.

On the other hand, to our prosperous 21st-century civilization, by far the wealthiest in history, architectural ornamentation costs so little — because it can be mass-produced, and/or because we have so much food that we can afford paying specialized craftsmen instead of having a population of 75% farmers — that it has become gaudy and tasteless, which is why no one builds it anymore.

Scott Alexander points out that these things can’t be true at the same time. Either architectural ornament costs more than it used to, or less. So which is it?

First, let’s define some terms. I trust that most people have an intuitive understanding of what architectural ornament is. But to be clear, I’m talking about anything that is strictly aesthetic and serves no structural or functional purpose. Things like ornate masonry, statues, bas-reliefs, colorful painting, or elaborate metalwork.

A column, for instance, can be structural, but if it’s like the Trajan Column in Rome, i.e. full of sculpted imagery and not part of any building, then it’s more of an ornament.

A building can be more or less ornate. On the extreme end of the spectrum, you get things such as the 18th century rococo style in Europe or the insanely detailed temple architecture of southern India:

On the other end, you get things like the International Style, which attained style supremacy in the mid-20th century and did away with (almost) all ornamentation. For example, the Seagram Building in New York City:

Because architectural ornament encompasses a vast diversity of things, it can be tempting to say, “Well, surely some kinds of ornament have become more expensive over time (such as large mosaics that must be painstakingly assembled with specialized labor), while others have become mass-produced (such as cheapo garden statues). So there isn’t really a mystery: the mass-produced kinds have lost status, and the expensive kinds have just become too expensive.”

This is true, but I don’t think it’s a compelling argument.

… Or at least, I didn’t think so in November of 2021. Annoyingly, the draft ended here.2 It never explained why that argument wasn’t compelling, leaving the me of March 2024 to figure it out.

And — at first glance, the argument does seem compelling. It’s definitely true that “ornamentation” can mean quite a few things. So the apparent contradiction may not be one: half of all ornamentation may be cheap stuff that nobody cares about except nouveau riche McMansion owners, and the other half is custom metalwork or something that costs a fortune since it takes a specialized craftsman a week to make at a rate of $50/hour.3

Still, you’d expect at least some architectural ornamentation to fall between those extremes. And you’d expect that at least some rich people would gladly pay the $50/hour rate to get beautiful custom metalwork on their newly built house.

Perhaps the explanation is this: now that the Industrial Revolution has occurred and mass-produced ornamentation exists, there isn’t an easy way to tell if something is custom or mass-produced. After all, these words describe properties not of the objects themselves, but of the processes that made them. That beautiful, intricate metal gate — was it lovingly crafted by an artisan according to unique instructions, or bought at a hardware store that sells hundreds of copies?

Another consequence of modern production is that we have all sorts of techniques to fake expensive materials. An ancient king could impress the commoners by gilding his palace with actual gold leaf. Today anyone can buy a can of golden spray paint and make anything yellow and shiny, which has the unintended consequence of making almost nobody be impressed by Donald Trump’s Trump Tower penthouse.

If these hypotheses are correct, then it doesn’t matter whether any specific kind of ornamentation is expensive or cheap. What matters is that it could be cheap. The very existence of mass-produced decoration degrades the status of non-mass-produced decoration.

Unless, of course, you can send a signal of expensiveness that isn’t easy to fake. One such signal is old age: there are comparatively few old buildings, and we can’t (by definition) make new ones. So most people find ornamented old buildings beautiful, and rich people who care about status like to buy them to display their wealth.

Another non-fakeable signal is architecture that is legitimately difficult to build from a structural standpoint. Or, as an Astral Codex Ten commenter put it:

[You] pay astronomical contracts to a scarce set of elite-approved architects, so that they build crazy structures that make engineers cry. Because that will actually rise the costs of construction unnecessarily by an order of magnitude or two.4

In other words, whatever money the rich people of yore would have poured into ornamentation now goes into innovative engineering. Which is why the kinds of buildings that win architecture prizes nowadays tend to look like this:

So my argument above wasn’t compelling after all: it’s true that there’s both expensive and cheap ornament, but that doesn’t matter. Almost all ornament is now cursed with the possibility of being replicated endlessly by modern industry. So — to the extent that the beauty of ornament is attributable to its use as a wealth and status symbol, which I think is a great extent — it’s rarely worth adding it to any architectural project.

(Is this what I meant back in November 2021? Almost certainly not — I don’t recall having ever thought that thought before today. But sure. Let’s go with that.)

Okay, that was an interesting explanation. If I’m lucky, it might even be true! Another entry to the long list of solutions to the unsolvable puzzle of modern architecture.

But it doesn’t tell us how expensive ornamentation is. I told you this was a failed essay. All I can do, apparently, is to deflect the main question. (“It depends!”)

Ultimately, though, I might as well take a guess. And my guessed answer would be something like, “On balance, ornament is much cheaper than it used to be, but still not quite cheap enough.”

(Ugh, what an equivocating answer. But it’s the best I can do.)

Put differently, architectural ornament might be stuck in a trap. It has become too cheap to function well as a status symbol, but not cheap enough that random middle-class people can buy it and add it to their houses on a whim.

Maybe this is how things fall out of fashion in general.

Take something that started out as extremely rare and expensive. Pineapples, say. Exotic, striking in appearance, tasty — and extremely difficult to grow in 17th- and 18th-century Europe. Aristocrats loved pineapples. Wikipedia says that “they were initially used mainly for display at dinner parties, rather than being eaten, and were used again and again until they began to rot.” Rich people even used pineapples as a motif for architectural ornamentation, sometimes to absurd proportions:

Eventually, the market responds to this demand. Businesspeople develop new methods of cultivation and transportation. James Dole of the Dole Food Company becomes the “pineapple king” in Hawaii. Flooded with new supply, the price of pineapples in Europe falls — and suddenly pineapples aren’t “in” anymore. Nobody cares about your stupid pineapple building. Some middle-class poseurs keep displaying them at dinner parties, not realizing that they’re ridiculing themselves. Yet, at least at first, pineapples aren’t so cheap that it becomes common to eat them as regular fresh fruit and get your daily dose of vitamin C.

Someone writes an essay pondering the deep question, “Why are people not displaying pineapples at dinner parties anymore? Because they’re too expensive,” they say. “There’s no point in spending the equivalent of an excellent bottle of wine on something that will barely even impress your guests.” But that would be exactly backwards — if pineapples were still expensive, they would impress the guests!

This is a half-fictional example: I don’t know whether pineapples went through such a low period, and I’m guessing that nobody ever wrote that essay. But it is true that pineapples used to be expensive, and now they’re not. Fortunately, the demand for them never got low enough that production just stopped. Eventually the prices dropped so much that even poor people can now get a pineapple at a grocery store for a couple of bucks.5 It probably helps that pineapples are a small consumer good for which supply and demand are elastic.

Architectural ornament is a more complex kind of good — it’s tied to housing, which, as everyone knows, is a very complicated market, subject to all sorts of rules, and involving large sums of money — so I can totally believe that it’s stuck in that limbo of being simultaneously too cheap to function as a status symbol, and too expensive to be usually worth getting.

If that’s accurate, we can discern a possible path forward, for those who think ornamentation should return: make it really really cheap. Using new materials, robotics, AI, whatever, we would need to reach the point where there’s no cost difference between a regular brick wall and a wall full of intricate sculpture.

Only then would people regularly commission ornamented buildings, not because they want to display their wealth, but just because they like the textures, the colors, the shapes. I predict that this will eventually happen — and that the architecture of the future will not be made of smooth gleaming surfaces, as sci-fi has accustomed us to, but of dazzlingly varied buildings, full of interesting design choices, of statues, mosaics, and metalwork, all expressing the individuality of their owners just like we do with clothing today.

At least, I hope we get there. I may be totally wrong. After all, no one really understands anything about ornament — least of all myself.

Another confession: that opening paragraph was written on December 19th, 2023. So it took me another three months to “impulsively” finish and publish this essay.

There was actually one more piece at the end of the draft, this mysterious sentence:

Imagine a country so poor that 90% of the population works in the fields.

Where was I going to go with this? I have no idea. Probably something like, a poor country like that has very few human resources to spare making ornamentation, so probably only the monarch/leader and a small caste of elite people live in ornamented houses, in addition to a handful of ornamented temples. Everyone else lives in boring blocks of concrete/brick/wood/[insert cheap material here]. But how was this supposed to connect with the rest of the argument? Who knows!

Consider this comment from a relevant Astral Codex Ten post, by an engineer who “worked for 7 years in a machine shop”:

From my experience, metal, plastic, wood, foam and concrete ornamentation is QUITE cheap now when you can use mass-produced pieces. You're looking at a few dollars for a single piece of ornamentation (or perhaps 10s of dollars if it's large with more significant material costs, etc.) Much cheaper than any pre-industrial architect would have access to.

On the other hand, our custom ornate work was far too expensive for any of our customers to afford. An ornate aluminum pencil-holder we made for one of our long-time customers that we had an excellent relationship with would have easily cost $2000 at our standard rates. Custom work is still extremely expensive, and if you're making an architectural show piece you'll need a lot of custom one-offs and small batches.

Of course, if the custom ornate aluminum pencil-holder turned out to be a popular design that lots of people wanted to buy, it wouldn’t be particularly hard to set up a factory to make thousands of them for $20 apiece. There’s probably nothing super special about the design itself, other than the fact that it didn’t exist until they made that one-off specimen.

There was a reply to that comment that I found interesting as well: it pointed out that expectation of change — especially future economic growth — can change the calculus around how much money to pour into architecture. If you expect things to be very different 30 years from now, you don’t spend a fortune on architecture:

the Church that built Stephansdom and is building Sagrada Familia expects to be around in much the same form in another thousand years, with a religious ritual that has very similar space requirements and still-meaningful symbols. Google does not think this about itself. Cities building modern public housing do not think this about residential housing. Exurbs building McMansions expect future waves of redevelopment.

I don’t think that quite explains it; we still do build things that we expect to last a long time, and there are rich people who care about leaving a legacy or whatever. But it’s still an interesting thought, and may have some explanatory power in certain situations.

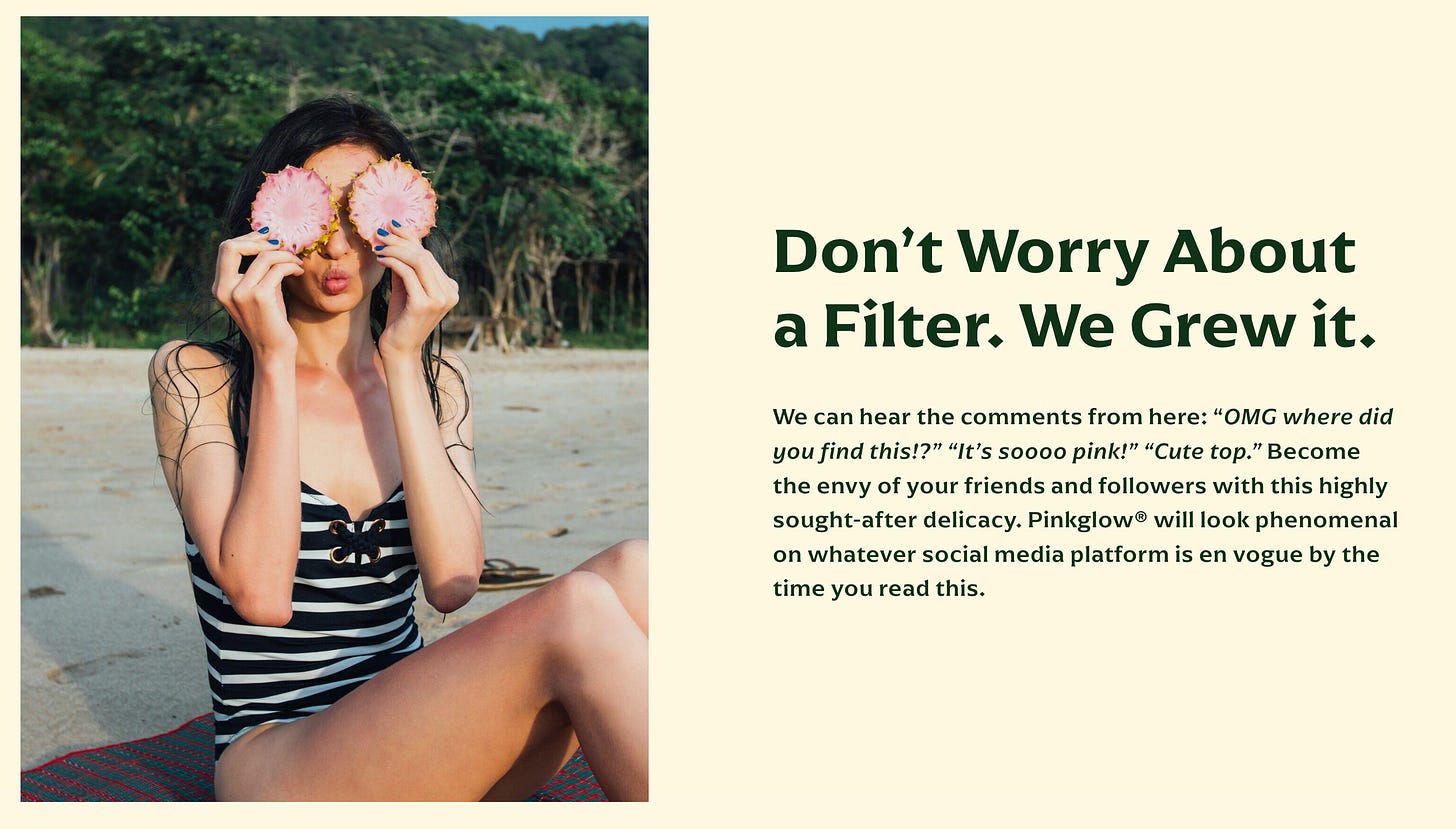

Though there are attempts to make pineapples a luxury product again! Del Monte has recently commercialized the Pinkglow pineapple, which has pink flesh and is explicitly meant to be Instagrammable:

I tried it last Christmas. It was cool, but not exactly worth the 3x price compared to a boring, regular yellow pineapple.

The nice thing about your articles is that even when they fail to answer their questions, they are still fascinating to read and think about. So this time.

I don’t think that you could have ever answered the particular question, because, I suspect, the question itself is framed in the wrong way. You see it as a question about architecture, while I’d think that the architectural expression of it is just one aspect of a much wider phenomenon.

For one, ornaments have not only disappeared in architecture, but all throughout everyday life. Cutlery used to be heavily ornamented (I still have a knife of my grandmother’s with all sorts of leafy ornament going around its handle), drinking glasses were, the salons of the Titanic were, and if you look at historical medical or lab equipment in a museum, you will see that even medical instruments and lab tripods for beakers used to come with lion feet. Modern times have done away with *all* of that, not only with architectural ornaments. And this, I think disproves your conclusion: for it is today trivial to 3d-print an ornamented knife-handle or pen holder for your desk, but nobody does so. It’s not that we don’t have the wealth to introduce beauty into our lives. It is rather that our standards of beauty have changed. Today, beauty is seen in the direct opposite of ornament: the stark simplicity of Zen, Japanese architecture’s straight lines and right angles, and its popular version: IKEA chic. One can still buy heavily ornamented garden chairs from cheap Chinese factories, but nobody wants to. We think of ornaments as garish and stark simplicity as aesthetically attractive.

Why have our aesthetic preferences changed? I don’t think that you could pinpoint one single reason. For lab and medical equipment, it’s clearly utility: medical knowledge about infections and contamination prescribes that such equipment should be easy to clean and disinfect, and the same applies to cutlery to some extent. You want a knife that will reliably be clean after rinsing it off, without having to poke through the ornament with a toothpick to remove any sticking bits of food.

Another thing is a cultural shift in the perception of luxury. I think it was Karl Lagerfeld who said (but I might be wrong about the source): “Today, luxury means to have an ironed T-shirt in your wardrobe.” The richest, trendiest men, the rulers of today’s world, come dressed in turtlenecks, T-shirts and jeans: from Steve Jobs to Zuckerberg. Even suits are suspect: only crooks like SBF or Trump insist on suits and ties. The more affluent the wearer, the more they “can afford to dress badly” seems to be the perception of it. And the same applies to architecture. Only a newly-rich lottery winner would build a mansion with marble doves fluttering over the ornate balconies. When Steve Jobs or Bill Gates build their houses, they are either modelled on simplified folk architectural motifs (“Mediterranean arches”) or clean modern lines without obvious ornamentation. But as with the T-shirt, which has to be “ironed” to signify luxury, the un-adorned Scandinavian style house has to have almost invisible ornamental touches: the contrast in the colours of the wooden beams; the positioning of the spotlights; the outside vista as it is framed through the windows. It is the now the *restraint* that makes the ornament aesthetically valuable, not the exuberance.

Yet another point might be efficiency: we love it. YouTube videos have to be short and to the point. Nobody likes flowery prose or long intros. We don’t have the patience for art that takes too long, or for a meal of many courses. McFood delivers the goods as quickly as possible. And this might also be a reason why we want our architecture to reflect this efficiency, the ease and speed that we want to surround and characterise our lives.

In the end (and sorry for the long comment), I don’t have any more answers than you. But I suspect that the answer to the architecture question is much more complex, involving a good deal of explaining the mindset of 20th and 21st century modernity. I also don’t think that our future will necessarily contain ornamented space stations *for the reasons you mention.* We might get ornamented space stations at some point, but I suspect that it will be just because of a swing in fashion, or maybe it will never happen because of reasons of practicality. Who knows. Anyway, a fascinating question and a great read. Thanks!

When I worked in a shop that was doing some custom-molded plastic parts, the story went that the first part off the line cost $200,000. Subsequent ones cost a nickel.