The first two video games I ever played seriously were on the Nintendo 64 console at the end of the 1990s. They were Pokémon Snap and The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time. I predictably grew up to become a lifelong Zelda fan (also Pokémon, but I already wrote about that), which has the predictable consequence that now that the new Zelda game has come out, it has absorbed most of my free time, leaving very little to write good blog posts.

In an attempt to write a good blog post anyway, let us discuss what is obviously the most important aspect of the new Zelda game: ruins.

(Spoiler non-alert: this post contains no spoilers, except in the most broad and impressionistic sense. Basically don’t worry about it.)

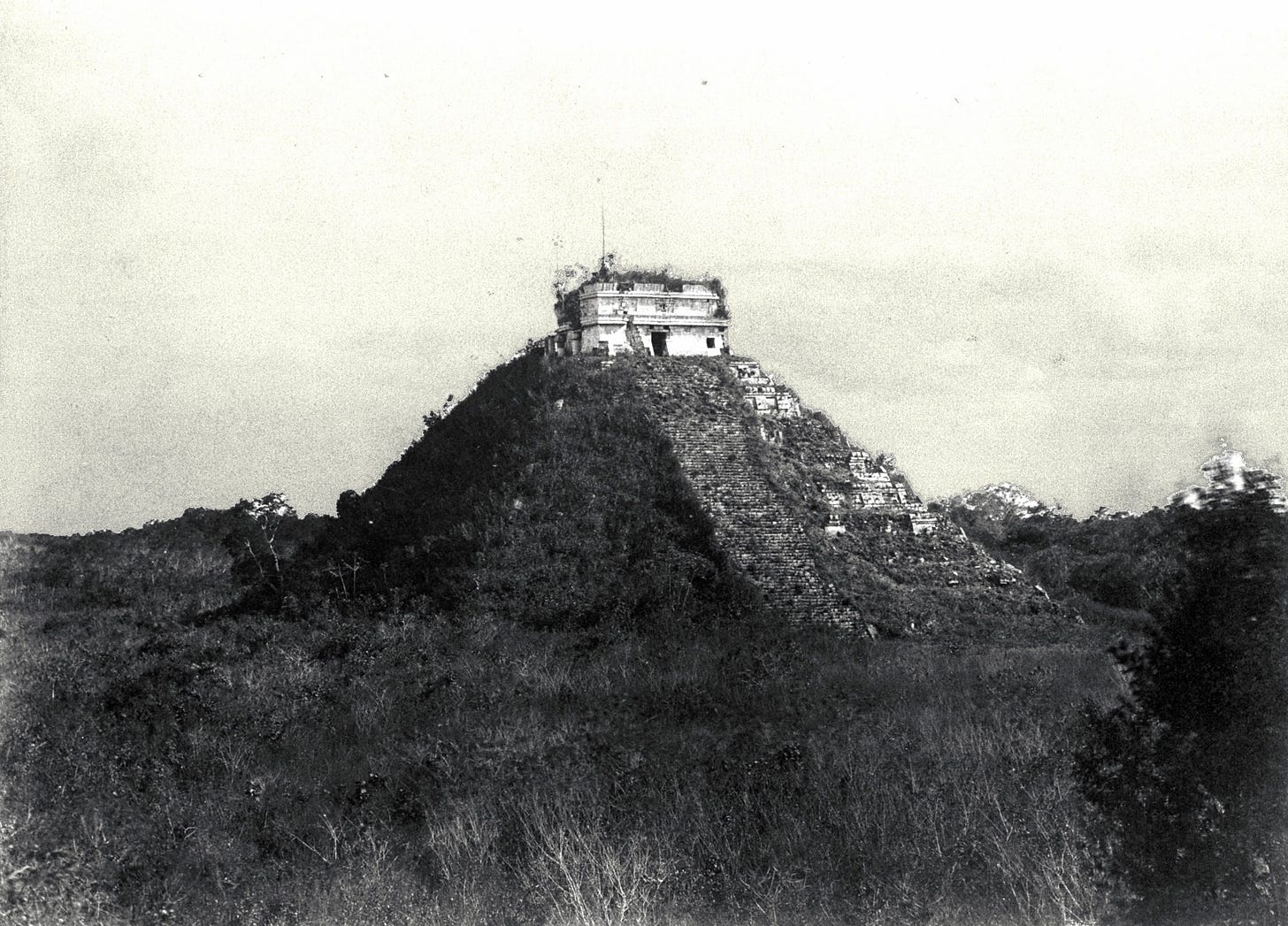

The Kingdom of Hyrule, which provides the setting for most Zelda games, is full of ruins. Always. Ancient temples galore, as do ancient tunnels, and ancient treasure caches, and ancient messages left by the sages of an ancient civilization. The latest incarnation of Hyrule, however, brings this to another level. Since the last game, Breath of the Wild, Hyrule has grown to enormous proportions to allow for an open world gameplay.1 Presumably, to make this giant world interesting to players, the developers had to add a lot of detail all over the landscape. So they added ancient temples, ancient tunnels, ancient treasure caches, and a lot of shrines in which an ancient advanced civilization has hidden ancient messages.

Narratively, the Kingdom of Hyrule is said to have suffered from a cataclysmic conflict a hundred years ago. In the new game, Tears of the Kingdom, which is set a few years after Breath of the Wild, we additionally visit the numerous ruins of a far more ancient, advanced civilization that fell from the sky. Everywhere the player walks or rides, there are ruins. Sometimes they are enormous complexes, sometimes they just a few blocks of old masonry ridden with vegetation. Sometimes they are used as a stronghold by monsters. Other times, as a place for the player to hide and recover. Of course, there are a few regular towns with well-maintained buildings and living characters across the kingdom. But mostly, as one travels the land, one is struck by just how much of it is filled with the ghosts of bygone times.

It’s not difficult to guess why developers like to add ruins to their games. Ruins are fun. They provide narrative justification for complex structures to traverse, for puzzles to solve, for treasure to find. A purely natural world would get boring quick. Nature, rich and diverse though it is, doesn’t provide the level of complexity that humans yearn for when they play games (and also when they don’t).

At the same time, ruins are simple. They’re dead; they contain no people. People are complicated: you need to write their dialogue, to give them the appearance of living real lives, to make them interact with the player in fun ways. An open-world game will have plenty of people, but you can’t fill Hyrule with the density of a modern-day city or even rural area. So instead, you add ruins. They give the appearance of being in a somewhat realistic setting, with some plausible history, at a very low cost.

And besides, ruins are beautiful. They have inspired artists for centuries: I don’t think I’ve ever had as much choice for the cover art of a post as I did for this one. The Wikimedia Commons database contains hundreds upon hundreds of examples of “ruins in art” spread out among dozens of subcategories. I ended up picking lithographs from David Roberts’s The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, and Nubia, an extremely popular travel book from early Victorian Britain, a time in which tantalizing illustrations of exotic ruins were the height of fashion. At the height of the Romantic era, Shelley wrote his most famous poem, Ozymandias:

Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies . . .Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare,

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

Today ruins attract crowds. The best preserved ones are national historic sites, and tourists flock to them. Museums are filled with the most interesting artifacts found in ruins. People make careers out of studying and excavating ruins.

Add it all up, and it comes as no surprise that video game designers, who are a kind of modern-day artist, should tap into what is clearly a timeless aesthetic tradition.

The reason I find this interesting is that this all contrasts with real, normal life. For most people, ruins play a very small role. Unless you purposefully seek them out, you can spend years not entering any ruins or even thinking about them. Most ruins are boring; they’re just old, decrepit buildings. Grandiose, well-preserved temples and palaces are rare. In a city, ruins are a massive opportunity cost; unless you can convert them into a tourist spot, you might as well raze them down and rebuild.

I realize that this is a North American speaking. North of Mexico, there aren’t that many cool ruins. Old indigenous burial sites are probably very exciting to indigenous people and some archeologists, but I cannot bring myself to care much. What ruins we have are often industrial, like this old rusty grain silo right in the touristy part of Montreal, an obviously ugly building that people (including myself) are somehow attached to:

It’s possible that ruins play a larger role in the lives of people living where great civilizations have once ruled. When I visited Greece, it seemed that each town had its own small archeology museum. I seem to recall that in countries like that, building anything can be a pain, because you never know if you’ll randomly find some priceless artifacts that need to be collected by specialists before you can carry on with your construction project.

But even then, I’m guessing that most ruins in countries like Greece are at most occasional annoyances, and only rarely a point of pride and fascination. The Parthenon, the Agora, the Temple of Apollo at Delphi are exceptions. The average Greek person, I assume, doesn’t care much more about some random broken old column in a field than I care about an ancient North American indigenous burial site.

Not caring about ruins, by the way, is normal human behavior. Before ruins became fashionable in Europe at the time of the Renaissance,2 they were mostly seen as a source of building materials. It seems anathema to us that someone could use stones from the Colosseum to build mundane houses elsewhere, but that’s what people used to do. Outside of cities, ruins of even great civilizations were overrun by vegetation and often forgotten, except in the lore of local people.

In theory, then, ruins are a source of fun adventure and artistic inspiration. But in real life, it seems correct to say that ruins are always one of:

boring

undiscovered (or at least, unexcavated)

turned into a tourist spot

While there’s nothing wrong with tourism, and in fact it is great that so many cool ruins are made accessible to visitors all over the world, well-maintained archeological digs and museums don’t offer much potential for adventure. There’s also something that’s aesthetically unappealing with the idea of a place being overrun with tourists.

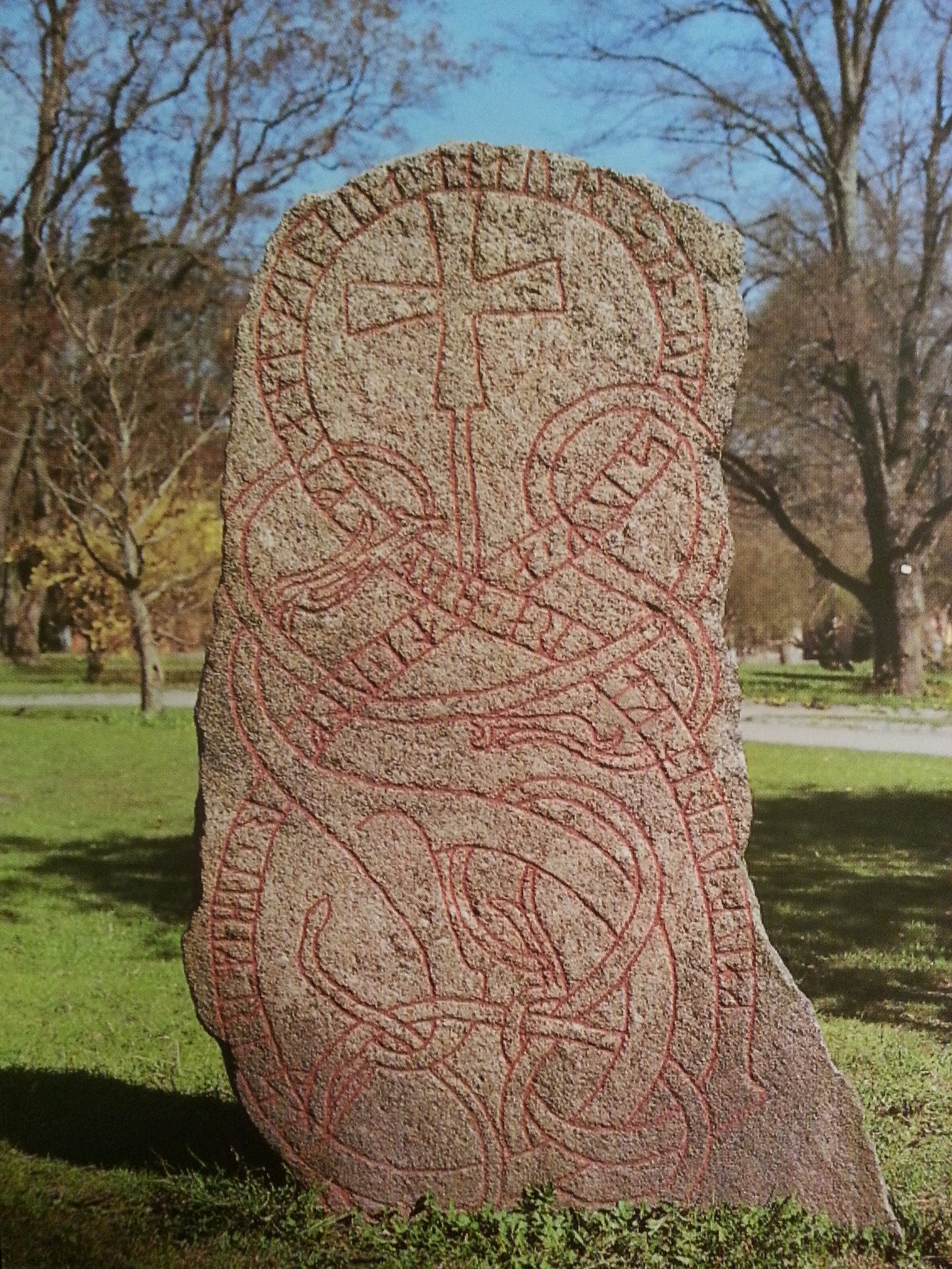

Undiscovered and unexcavated ruins are, by definition, difficult to find and explore (when it’s not outright forbidden). That difficulty itself can be a source of adventure. But few of us would go so far as trying to look for them. I once tried to hunt for Norse runestones on the outskirts of Uppsala, in Sweden; this wasn’t particularly adventurous, since I was just following the coordinates from an online map. But the stone I was going for seemed to be on some private farmland, and it was drizzling, and the land was full of random stones that I would have to look at one by one while trespassing, so I gave up. Thus ended my career of intrepid explorer of ruins.

Meanwhile, boring ruins can be made interesting. An old abandoned house in the countryside might make for a cool outing (if an unsafe and possibly illegal one). There’s a whole hobby called urban exploration that consists of entering ruined buildings. I think that sounds really cool, but it doesn’t exactly tickle my taste for mysterious civilizations. There’s an aesthetic to urbex, but it’s not the one of ancient ruins like in Greece and in art.

What remains, then, is the fictional stuff. The ruins in a game like Zelda are free from the above constraints: they can be fascinating, accessible, and mysterious, at the cost of being fake. In a game, you can casually explore a gigantic temple at the bottom of a valley that would unquestionably be one of the seven wonders of the world if it existed in real life.

Ruins in games are a superstimulus. They are like those Victorian-era paintings of vast, epic palatial complexes that were never actually built:

These paintings, like the ancient temples in Zelda and other games, exist as a figment of our imagination; their purpose is to tickle us, to tell stories, to make us dream. They are meant to allow us to escape the boredom of our daily lives. But in truth, we prefer the boredom; it’d be far worse to live in a disaster-struck place like Hyrule. Ruins are fun and beautiful, but they are very much dead, and the vast majority of us prefer to spend our time among the living.

According to the calculations from this Reddit post, the dimensions of a rectangle containing the Breath of the Wild and Tears of the Kingdom version of Hyrule are 7.4 × 5.4 km, for a total of almost 40 km², about two thirds the area of the Republic of San Marino. However, time passes 60 times faster in Hyrule compared to our world, which means that based on travel time, we can multiply these distances by 60 and get 447 × 325 km = 145 275 km², which is between the areas of Tajikistan and Nepal.

Apparently part of our modern fascination with ruins is due to the rediscovery, owing to random chance, of emperor Nero’s ancient Roman palace, the Domus Aurea, when a young Roman fell into a hole around the year 1500. Artists like Raphael and Michelangelo would crawl into the ruins to study its preserved frescoes.