Some countries are blessed with vast amounts of a specific natural resource, which they exploit or regulate by setting up a large state-owned monopolistic organization. In many places it’s oil. Sometimes cocoa beans. For tiny countries it might be phosphate. In Quebec, our greatest natural resource is our remote rivers, strewn across the almost unpopulated northern swathes of the Canadian Shield. By harnessing their strong currents we create large amounts of hydroelectric power, which give us low electricity prices and significant revenue from exports to other Canadian provinces and the United States. To produce and distribute this power, politicians from the 1940s to the 1960s embarked on a project to nationalize all hydroelectric companies into a large state-owned monopolistic organization, called Hydro-Québec.

The 1960s, especially, were also a time of great social upheaval and national awakening. We call it the Quiet Revolution — a time when, without fanfare, the French Canadians stopped calling themselves that, and became Quebecois; turned their backs on religion and grew more liberal; made education public and free; created a social class of businessmen, once the quasi exclusive domain of the English Canadians; and began talking of independence.

Hydro-Québec is perhaps the most potent symbol of that period. To many, it represents modernity, technology, and, importantly, the capacity of the previously impoverished Quebecois people to take their destiny into their own hands. Thanks to Hydro-Québec, a class of educated engineers and administrators emerged, able to build great projects, like the largest underground power plant in the world. Thanks to Hydro-Québec, the prices paid for powering our homes and industries is very low, and the profits belong to all. Thanks to Hydro-Québec we have almost no fossil-fuel–powered electricity generation, and are, on at least some metrics, one of the cleanest places on Earth.

It would be an understatement to say that Quebecers are fond of Hydro-Québec. It goes further than that. The company holds a special place in the national mythos. It represents collective success and wealth; it is a source of pride. Hydro-Québec is well aware of this, of course, and it works hard at reinforcing the feeling. It sponsors hundreds of organizations throughout the province. Its social media marketing team is top-notch and a frequent source of memes in the Quebec media landscape. It also offers free guided tours of several of its power plants, including some in remote regions, contributing to local tourism, popular education on electricity technology, and its own reputation.

In 2016, a documentary theatre play called J’aime Hydro, written and acted by Christine Beaulieu, became a hit — unusually for any play in Quebec, let alone a documentary one. J’aime Hydro translates to “I love Hydro[-Québec]”. It is about the relationship between Quebecers and their electricity company, as well as controversies surrounding past projects, and the big political question of whether Hydro-Québec should build new dams.

I saw the play in 2019, when it went on tour thanks to its wild success. It was pretty good, though its conclusion was, I think, wrong in retrospect; it suggests that Hydro-Québec shouldn’t dam any more rivers and instead focus on reducing energy waste, which has turned out, several years later, to be incompatible with the growing demand, partly from the transition to electric cars. Now politicians and Hydro-Québec executives openly discuss building new hydro plants or even going back to relying on nuclear.1 (And meanwhile, my own political evolution has led me away from this sort of anti-abundance mindset.)

But the most interesting thing about the play is that it exists at all. Why would anyone expect a play about a utility company to have resounding success? Clearly there is something to unravel there. Clearly, as the title suggests in a sort of extremely subtle fourth degree sarcasm,2 Quebecers love Hydro.

To be sure, they also love complaining about it. Those in the areas that are affected by new power plant projects, as well as environmentalists and indigenous advocates who worry about the local impacts, may see Hydro-Québec as a disrupting force. And everyone who has electricity at home is likely to moan about rate hikes or excessively long power outages sooner or later. But overall most Quebecers still love Hydro. And there is one thing that their jealous love will never let pass: anything resembling, directly or indirectly, a privatization of Hydro-Québec.

Since it is a politically unpopular proposal, it is rarely proposed, except by the rare libertarian think tank economist (only to be promptly shut down in public discourse). But occasionally, something vaguely shaped like that will come up. For example, the current center-right-ish government is working on a bill that would allow companies to distribute the electricity they produce to another private party,3 which is currently forbidden. It’s a small thing, really. A drop of liberalization (critics would say neoliberalism) in what otherwise remains a good old state-owned monopoly.

People have been up in arms about this. It is seen as a crack in Hydro-Québec’s monopoly on electricity distribution. If we do this, then we embark on a slippery slope towards full privatization! We squander our collective wealth! We privatize profits while we socialize the losses! I’ve been hanging out on the r/Quebec subreddit, and some of the comments are just… how to say? Someone suggested that merely putting “privatization” and “Hydro-Québec” in the same sentence should be considered high treason if the utterer of that sentence holds public office.

I find this bizarre. Hydro-Québec is, at the end of the day, just a utility company. One can, of course, strongly prefer that it remains under government control, but to see treason in merely suggesting a small amendment goes… beyond that. It’s as if Hydro-Québec had transcended the realm of the secular into the realm of the sacred.

At first I was puzzled by this observation. Why would people collectively consider an electricity company sacred, untouchable? Isn’t it obvious that such devotion would blind us to the potential benefits of — or at least healthy debate around — reforming or abolishing it?

But I guess it isn’t a particularly difficult puzzle. People elevate things to sacred status all the time. David Foster Wallace wrote that “Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship.” I don’t know if he’s right, but if he is, perhaps it was inevitable that, when Quebecers cast off the tight spiritual rule of Roman Catholic priests during the Quiet Revolution, their collective devotion would find new targets.

Some of those targets are representations of national culture. In most places, symbols like flags, buildings like government palaces and national museums, and people such as monarchs and presidents are given more-or-less sacred status.4 But Quebec is an incomplete country, unable to worship pan-Canadian institutions and symbols, which Quebecers don’t see as relevant to them, and also unable to fully make its own, due to being part of Canada. We have a king, but we derisively (and inaccurately) call him the King of England, to emphasize how he isn’t really ours.

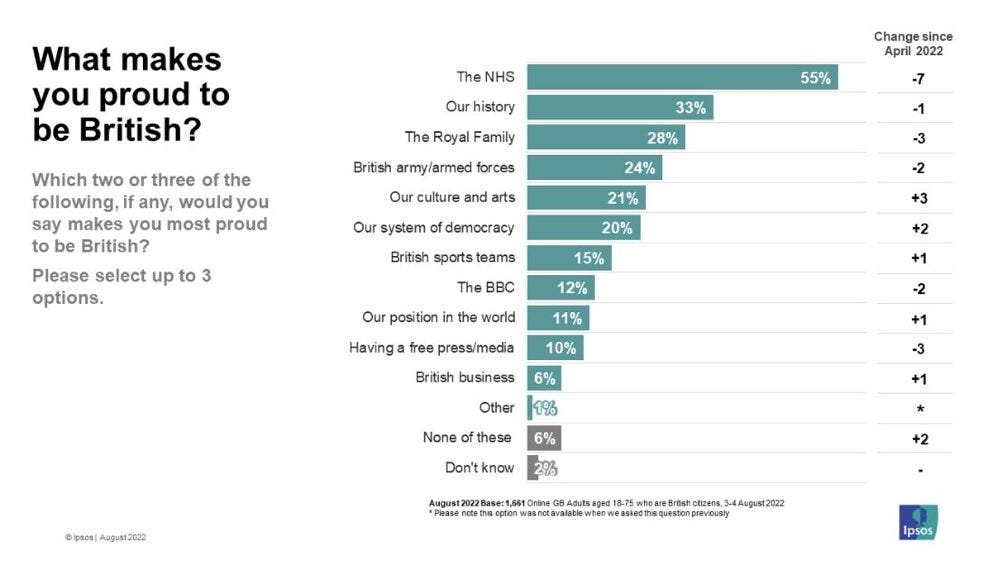

Although, to be fair, the main country for whom that king serves as national symbol derives more pride from its National Health Service than its royal family, so I suppose this is a much wider phenomenon than just Quebec.

So then we cling to worshipping collective institutions that we feel we truly control. It can’t be private corporations: those are controlled by stockholders, and successful Quebec companies (the cliché in the press is to call them fleurons) routinely end up under foreign ownership. People used to be attached to the Cirque du Soleil, but whatever sacredness it had turned sour when its Quebecois owners sold most of it to American and Chinese investment groups. What remains is public institutions like the welfare state, and state-owned monopolistic organizations, like Hydro-Québec or the SAQ, which controls the distribution and sales of alcohol throughout the province.5

This is a bit suboptimal. State-owned monopolistic organizations aren’t usually great from an economic perspective. They might be good sometimes, certainly; some defend them in situations of “natural monopolies,” like distribution networks, where it’s a single company naturally tends to end up controlling the entire thing. (Though I gather that the existence of such a thing is somewhat controversial.) But in any case, we should be able to debate it.

So ideally we would set up better targets of worship — ones that are attractive as symbols but don’t actually matter that much in terms of real outcomes.

I think this is one of the more subtle advantages of monarchy, especially the kind where the king or queen is a figurehead and doesn’t do much: it serves as a cultural anchor without actually affecting most policy. Hence one of my more idiosyncratic beliefs, which is that Quebec should be not only independent, but an independent kingdom: I suspect it’d be good to keep the institution of monarchy but set up our own royal family, separate from the British and Canadian one. (To be clear, almost nobody thinks this, and I wouldn’t, like, advocate for it seriously. But you know. One can dream.)

More generally, I’m basically restating the point from my essay about libertarianism and culture: the main reason governments exist is to provide a way to express national culture and unify people around it. Libertarians and economic liberals who forget about this need will find themselves facing formidable political obstacles — like the rants of a thousand angry Reddit users.

It’s important to recognize this situation, because it’s probably true that Hydro-Québec is due for a little bit of liberalization. Nothing catastrophic will happen if companies can produce electricity and sell it to their neighbors; it’ll probably be good, even if it gets us on a “slippery slope.” But in any case, we should be able to discuss it in a levelheaded way, rather than being blinded by love.

There used to be one nuclear plant in Quebec, but it was shut down in 2012. We’ve never really needed it, thanks to the rivers, though my view is that the more energy, the better, so we should indeed build some.

I took the idea of fourth degree sarcasm from this blog post by Benjamin Gregory Carlisle, where it is defined as “saying what you mean, and saying it sincerely.” It may be questioned whether such a thing exists and differs from non-sarcastically saying things sincerely. Carlisle isn’t very helpful in explaining it, leaving, “as an exercise for the reader, the task of coming up with some examples.”

I submit that “J’aime Hydro” is one. Christine Beaulieu, like most Quebecers, really does love Hydro-Québec. But she loves it after months of researching it, interviewing people all over the province to talk about it, and openly asking if it acts wrongly in some respects. When she says “I love Hydro,” she is sincere, but the title leaves readers and spectators wondering: Is she being sarcastic? Are we supposed to love Hydro? Will we still love it after seeing the play? “J’aime Hydro” as the title of a documentary is a rich statement, far richer than saying it naïvely would be.

To be precise, private companies (or individual people for that matter) are allowed to produce electricity, but not to sell it to anyone other than Hydro-Québec. The bill would allow them to sell it to another private client, but only if that client is located near the production site. For instance, someone could set up a small power generator as part of their factory, and then sell the surplus to another factory on an adjacent site.

Some going so far as having laws against lèse-majesté, most notably in Thailand.

Since the cover image for this post is a painting of a Soviet hydroelectric station, featuring a statue of Lenin, it’s worth pointing out that communist countries tend to have a lot of this worship of collectively owned organizations. See also the national emblem of North Korea, which features a hydro plant!

In the early 90s HL&P Houston lighting and power decided to go private. I guess it was put under pressure politicians paid off to a company called Centerpoint and the distribution is auctioned off I think but the distributors I’m pretty sure collude with one another. It’s an absolute mess now contracts with small print hidden fees, kilowatt one is expected to use for one rate if we go below your charged another rate sometimes they charge you what they think you’ll use. It’s a mess.

One thing that should be public and that’s public utilities. as a right leaning person, I’ve always regretted that Houston lighting and power went private.

Oh, and the infrastructure is now shit .

Category one hurricane tins of thousands of people without power for weeks never heard of before in the history of Houston hurricanes

Mayor Lanier is going to get to the bottom of it. He’s a Democrat he thinks like a right wing

The little greedy bastards are going to get in there and fuck everything up it will take a decade all the good intentions. Those people will die off will be replaced by people that never made the deal.

I can relate to the importance given to public hydro-electric projects. I grew up in Kerala, in South Inidia. The majority of the electricity in the state is from hydrolectric plants. Every year we were taken to one of these projects – since they were typically created by damming a river or tributary, one side would be public garden. It was mostly a great day out with our classmates for us though, we didn’t give too much attention to the guided tour of the power plant.