The First Culture Warriors

Akhenaten, Tutankhamun, and the ripple effects of cultural conflict 𓁪

Sometimes life sends you a sign that, try as you might, you are an inferior blogger than the ones you look up to.

I wrote a big review of a book about pharaoh Akhenaten, entered it into the ACX book review contest, and didn’t make it to the finals. I know why: my review was missing some contemporary insight that would transcend the book and make it more than just a retelling of Akhenaten’s story, which is already well-known (among history nerd types, at least). With all the hard work of processing and summarizing the book, I had no creative energy left to make a clever point of great contemporary relevance, other than my weak “don’t engage too much in wild historical speculation.”

And then, two weeks ago and seemingly unconnectedly, Scott Alexander of ACX used the Akhenaten story to make a clever point of great contemporary relevance.

It’s about cancel culture, and how cancel culture is a weapon that can be wielded in alternance by different political camps. When a camp has been culturally dominant enough to wield it, but then loses that dominance, the other camp might be tempted to use it in retaliation. That team might claim that this is fair given that cancel culture is a new development and its opponents are the first ones to ever benefit from it. Scott uses Akhenaten (and other historical examples of persecution) to show that this argument is dumb:

“Given that liberals invented cancel culture ten years ago, shouldn’t we get ten years of conservative cancel culture, just to be fair?” asks someone totally divorced from historical reality. …

People joke that “cancel culture began with Socrates”, but I don’t buy it. Seen on Wikipedia:

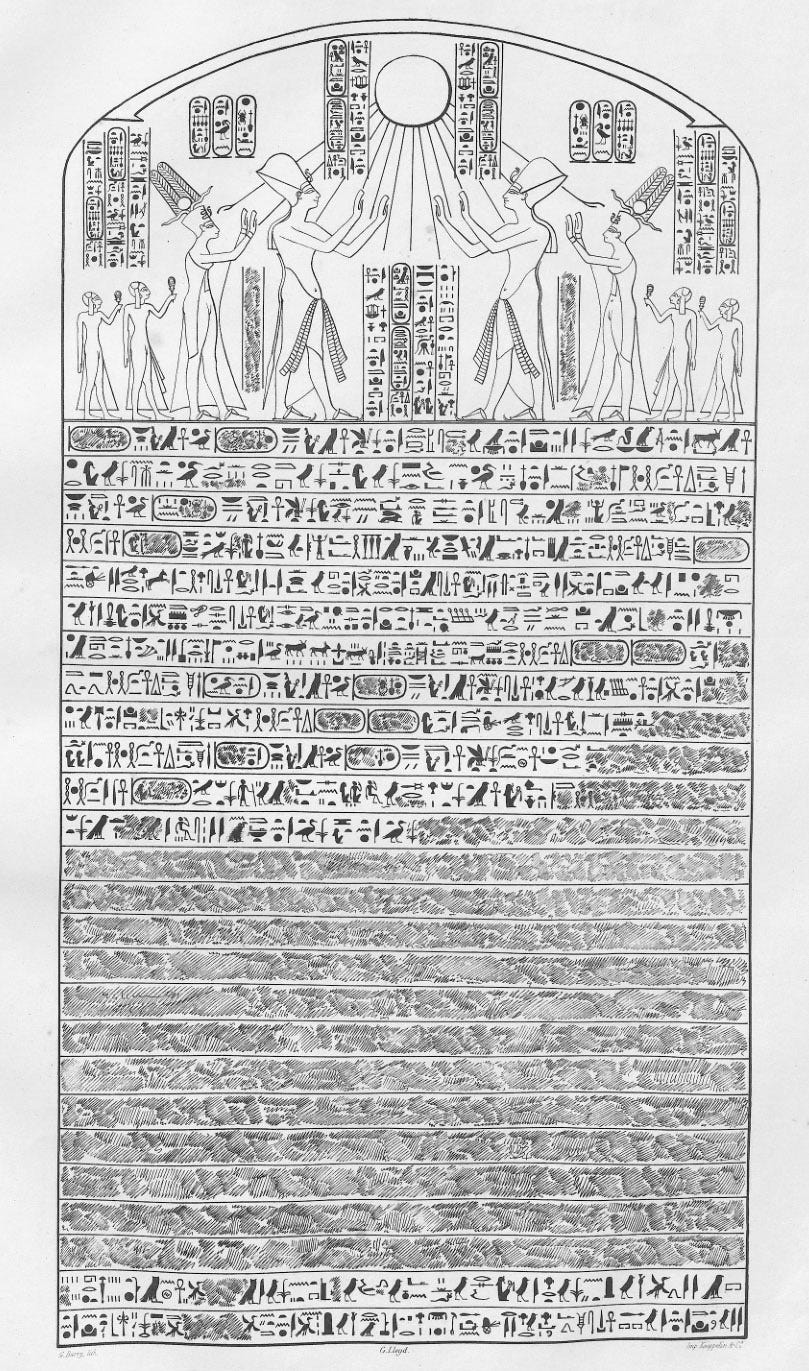

[In 1345 BC], Akhenaten … ordered the defacing of Amun's temples throughout Egypt … Archaeological discoveries at [Amarna] show that many ordinary residents of this city chose to gouge or chisel out all references to the god Amun on even minor personal items that they owned, such as commemorative scarabs or make-up pots, perhaps for fear of being accused of having Amunist sympathies.

When the Priests of Amun came back into power, they took the low road:

This culture shift away from traditional religion was reversed after his death. Akhenaten's monuments were dismantled and hidden, his statues were destroyed, and his name excluded from lists of rulers compiled by later pharaohs.

And since righteous vengeance had been attained and both sides now had experience with cancel culture being morally wrong, everyone agreed the ledger was balanced, and nobody ever tried cancelling anyone else ever again.

Like I said: a much better writer than I am.

But I have written a big book review on this topic, which is better than reading Wikipedia, so I have a few thoughts. Let this post serve as a belated attempt to cleverly connect Akhenaten to our own contemporary situation.

Why is Akhenaten’s story remarkable? Why was I, and the authors of the book I reviewed, and many others, drawn to it? I think the answer is that it is the first indisputable evidence of particular cultural phenomena.

Sometimes people claim these phenomena are grand things like “science” or “individuality.” But like I wrote in my review, it’s a big stretch to call Akhenaten “the first scientist” because he recognized the effects of sunlight on nature or “the first individual” because he had ideas outside the Overton window of his time and place. Obviously there were people well before the 14th century BC who made observations on nature or had ideas that went against local customs.

More interestingly, he might be “the first monotheist,” since he elevated the sun disk Aten as some kind of sole god, replacing some of the rest of the Egyptian pantheon. But the specifics of his religious reforms are hotly debated by Egyptologists, and there are many reasons to think his new cult wasn’t anything like the monotheisms of Moses or Jesus. When you think about it, saying “my favorite god is the only good god, all the other ones suck, especially that one that my enemies especially like” has probably been a regular feature of polytheism since its beginnings, and is quite different from the complicated theology that later developed in the ancient land of Israel. Also, the few hints we have about Akhenaten’s motivations suggest it was either an attempt at creating a theology centered on the time of creation before the other gods existed, or a political move to accrue power to himself, his wife, and a small elite of loyal priests and officials. Either way, there isn’t a consensus that monotheism is the best word to describe that situation.

So Akhenaten may or may not be the first monotheist. However, I’d say he has a plausible claim at being “the first culture warrior.”

Or at least, the first culture warrior for whom there is substantial documentary evidence. Surely lively discussions on culture have been happening ever since there has been culture.1 And it is certain that earlier military or political conflicts, like, say, the unification of Egypt around 3,150 BC, or the conquests of Sargon of Akkad around 2,300 BC, had a cultural dimension. But we don’t know how that played out, and in any case it seems safe to assume that cultural or religious questions were secondary to things like “how power-hungry the local successful warlord is.” Beyond that, we don’t really have any evidence of specific controversies that were primarily concerned with matters of theology, language, or the way society is organized.2

For all we know, there never was, before Akhenaten, a culture war that wasn’t also a regular war and yet managed to totally disrupt an entire large country.3 It’s possible that the magnitude of the Atenist reform and counter-reform is what is truly unprecedented.

And it really did involve some features that find interesting analogues in today’s culture wars:

The top guys using the controversy to advance their own politics (Akhenaten may have used his religious reforms to consolidate his power; his maybe son Tutankhamun may have reversed them to achieve the same goal)

Symbols of the dominant political faction being displayed everywhere (the Aten itself)

The elite class having to repeat the official messaging from the top guy in order to keep their position as elites (everyone in Akhenaten’s capital at Amarna had little altars to show devotion to Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and the Aten)

People on the losing side posting complaints on social media (a priest wrote a graffiti on a temple wall, lamenting about being abandoned by Amun)

Most people not actually caring about or being directly affected by the culture war (there’s very little evidence of the Atenist heresy involving anyone normal outside of the two capitals of Waset and Amarna)

The officially-sanctioned destruction of signs and monuments of the losing side (Akhenaten ordered that people remove mentions of Amun and “gods” in the plural from various inscriptions; after his death, his successors did the same with him and Aten, and destroyed his personal temple). This is the part about cancel culture or, under its cooler classical Latin name, damnatio memoriae.

Still, I don’t want the analogy to look too strong. There are several ways in which it doesn’t hold up that well, such as:

As far as we know, the Atenist heresy happened due to the actions of a single person, Akhenaten himself, so it’s unclear that we can speak of a “cultural” movement. The quick reversal to traditional religion a few years after his death suggests that Egyptian culture hadn’t in fact changed much.

Damnatio memoriae was probably less about destroying the reputation of living persons (like modern cancel culture) and more about erasing the official records of dead persons in order to make some sort of legitimacy point. A few generations prior, pharaoh Thutmosis III erased many references to his aunt and predecessor Hatshepsut, possibly because it made for a cleaner lineage (Thutmosis I, II, then III) without a woman in it.

It’s also clearly something done by the government and elite, as opposed to a bottom-up movement of the masses memetically deciding to attack some personality, which is what “cancel culture” usually refers to (as opposed to, say, “censorship”).4

On balance, I’m unconvinced that the Akhenaten episode exemplifies modern cancel culture, unless we extend the concept so much that it becomes a useless synonym for “censorship” and “persecution.”5 But the broader idea of a culture war fits well. The reason Akhenaten’s reign is interesting is that it shows how people took obscure points of religious doctrine — things like “who should bring about cosmic order” — really seriously, to the point of messing up existing social institutions in ways we can detect 3,300 years later, long before all other known instances of this. That’s a useful piece of evidence about how human societies work.

Hence I agree with a slight reinterpretation of Scott Alexander’s point: even though some specific phenomena like social-media-based cancel culture might be relatively novel, when they’re seen more broadly as part of the concept of culture war, there really is nothing new under the Aten. Don’t feed the flames of culture war under the pretext that the situation right now is unique and special — it hasn’t been unique or special since at least 1,350 BC.

The ACX post later concludes:

The priests of Amun probably felt pretty great revenge-cancelling the priests of Aten after they regained power. But nobody remembers them today and they’re not part of the story of human progress. Jefferson and Madison wrote the First Amendment to defuse the entire conflict from above, and everybody remembers them, and it actually made a long-term difference.

This paragraph is weak, suggesting a silver lining — maybe there is less of a quality difference between Scott Alexander and myself than I thought!

It’s weak first because of the huge time difference. Sure, nobody remembers the priests of Amun, but they lived 3,300 years ago. Nobody remembers anyone from that time. (With rare yet obvious exceptions to which we’ll come back in a minute.)

Meanwhile, Thomas Jefferson died in 1826 and James Madison in 1836, both less than 200 years ago. And they lived at a time that was far more technologically advanced, and therefore able to record events and constitutional amendments, than the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. Also, their country still exists, is still the top superpower in the world, and hasn’t been conquered and culturally assimilated by the Persians / Macedonians / Romans / Arabs yet.

Besides, I think Scott Alexander is grossly overestimating the collective memory of Jefferson and Madison here, especially for the 96% of the population that lives outside the United States. I, a history nerd who has been known on occasion to read Wikipedia pages like List of multilingual presidents of the United States, had totally forgotten the existence of Madison (4th president, and considered “the Father of the Constitution”). I sort of knew about the First Amendment in the sense that the US has some sort of strong legislation around free speech, but I know very little of the details, including who was responsible for it or what it actually protects.

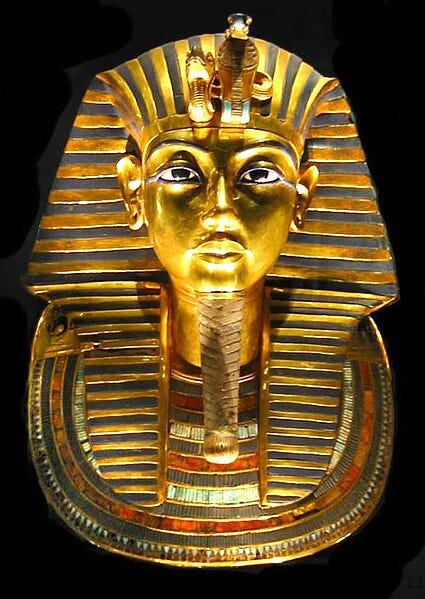

Then of course there’s our first rare yet obvious exception: Akhenaten himself. The main actor in the Eighteenth Dynasty culture wars is still, despite a large-scale effort by his successors to prevent precisely that, well remembered today. Among ancient Egyptian figures he’s probably among the top 5 in terms of fame.6 Among 14th century BC people worldwide, he’s probably second only to Tutankhamun, and then only because of Tutankhamun’s iconic funerary mask.

And speaking of Tutankhamun — have you noticed the last four letters of his name? That’s right! Tutankhamun was, at least in a technical sense,7 the leader of the priests of Amun who revenge-cancelled Akhenaten. So “nobody remembers [the priests of Amun] today” is strictly false; in fact, I think their most recognized member is still more famous than either Jefferson or Madison, despite having lived three millennia before them. Granted, this is a bit of an accident due to Tutankhamun’s tomb having never been looted. But still.

What’s the lesson here?

Unfortunately, I don’t share Scott’s optimistic take that acting to prevent cancel culture and culture wars will make you more famous in the long run. Culture wars can have enormous ripple effects. The Aten-Amun controversy eventually died out, but that’s because Egyptian civilization in general was almost entirely transformed by foreign conquest. So it’s easy, now that ancient Egypt is a distant memory, to portray both Akhenaten and Tutankhamun as failures. But the latter and his camp influenced religion for at least 1,000-1,500 more years!

Besides, if Akhenaten had been just a bit more successful, for instance by living to the age of 40 instead of 30, he could actually have succeeded at changing Egyptian culture durably and influenced the course of its civilization and the rest of the world. Even with his limited success, and the reputation he gained as a weird heretic who didn’t deserve to have his name on king lists, my guess is that ancient Egyptian people were still talking about him 200 years later.

And the rest of history is replete with examples of culture wars whose effects are still felt long after the events. Consider basically all religious splits whose branches are still practiced: Judaism vs. Christianity vs. Islam; Orthodox vs. Catholic vs. Protestant Christianity; Sunni vs. Shia Islam; Theravada vs. Mahayana vs. Vajrayana Buddhism. In medieval Europe, the Cathars were considered heretics by other Christians, who engaged in a culture war that eventually degenerated into actual war and the total extermination of Cathar thought. It’d be nice to say that nobody remembers the people who waged that war and cancelled the Cathars, but they’re just regular Catholic medieval people who would go on to fully control Western Europe indefinitely. Even political scandals that feel like they should be minor can reverberate across time if they become the fuel for a culture war: the Dreyfus affair, a story of false conviction, espionage, and antisemitism in late 19th century France, became such a big deal that we can still detect its effects 125 years later if we squint.

So waging a culture war is nowhere near a guaranteed ticket to be forgotten. It’s actually a pretty good way to leave a legacy, especially if you win. Even if you don’t win, you can be remembered at least as a villain, or more neutrally as a charismatic or unusual figure.

Fighting against that temptation — of cancelling enemies culture and fuelling cultural conflict — is worthwhile. But let’s not shy away from the fact that it’s a bit of a thankless job. Promoting liberalism and cultural diversity (whether that diversity is political, religious, linguistic, etc.) will never seem glorious to those who just want their own culture (ideology, religion, language, etc.) to dominate.

All the more reason to glorify those who do the thankless job.

I.e. for hundreds of thousand or even millions of years? I’m not sure how we’d delineate the start of human culture, but it’s an intriguing question. The beginning of language maybe? The first evidence of tool use?

Some indirect evidence comes from Sumer in Mesopotamia. We know that the Sumerian language, the first to ever be written down, declined and was replaced by Akkadian as the everyday language of Sumerian civilization by 2000 BC. For a long time, Sumerian survived as a sacred or ceremonial language in Mesopotamia, much like the role Latin played in post-Roman Europe. I’m sure the transition must have involved cultural controversies, but as far as I know there isn’t a surviving text describing that.

Also in Mesopotamia, we could see early law codes as evidence of cultural debate. The earliest known one, which is lost but has fragmentally survived in other texts that reference it, seems to have been created by king Urukagina of Lagash in the 24th century BC. There’s also the much better known code of Hammurabi in 18th century BC Babylon. In both cases they implicitly suggest that society had to be changed, and the rules are an attempt at providing that change. But we don’t know how the people of Mesopotamia reacted to the proposed change, or whether there genuinely was something analogous to a “culture war” around them.

To be fair there barely even were countries other than Egypt at the time. The Hittite Empire, some Mesopotamian states including Assyria, and the Shang dynasty in China. I guess a few city-states here and there.

Inspired by this comment:

Diocletian, Akhenaten and the priests of Amun all had direct control of the relevant institutions, and were all plainly exercising power in pursuit of their own projects. The policies of the first and last probably won plenty of chattering class support, but it's hard to imagine any of these guys really cared.

Scott’s original post makes many good points about cancel culture that are unrelated to Akhenaten, including that we should actually figure out what it means.

Other contenders include Cleopatra, Tutankhamun, Ramesses II, Nefertiti, and Khufu. Cleopatra is much more recent, having lived from 69 to 30 BC, a time of which we have way better records. Tutankhamun is famous due to the fortuitous conservation of his tomb, and he and Nefertiti are closely related to Akhenaten anyway. Khufu is famous just because of his association with the Great Pyramid, but we don’t know much about him. That leaves Ramesses II (a.k.a. Ozymandias) as the main comparable figure. I think Ramesses II is a bit more famous, and for better reasons, being the longest-reigning pharaoh and all that.

He was a teenager pharaoh (he died age 18 or 19) so it’s questionable whether he was actually the one behind the push to restore the traditional religion. But he was at the very least the symbolic authority who was responsible for it.