Are we better at telling stories today, compared to any given point in the past?

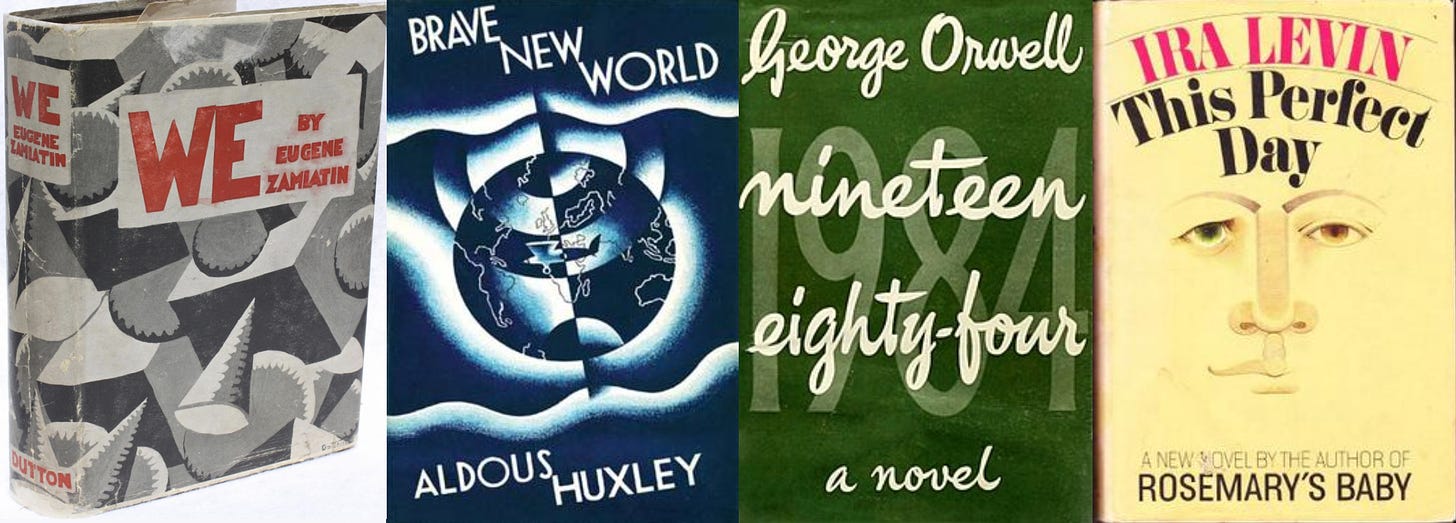

To answer this tantalizing question, a cherry-picked, subjective case study that may nevertheless prove illuminating: classic 20th century dystopian novels. The most famous books in the genre, most of which I read or reread in the past few months, might be, in order of publication:

We (1924), by Russian writer Yevgeny Zamyatin, considered a foundational influence on the entire genre;

Brave New World (1932), by Aldous Huxley, who denied being influenced by Zamyatin even though George Orwell believed he must have been;

Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), by Orwell;

This Perfect Day (1970), by Ira Levin.

(One might also cite Fahrenheit 451 (1951) but I haven’t read that one yet, although as of last month it is officially Sitting On My Bookshelf.)

Of these, the best novel in terms of whatever the phrase “literary significance” means is probably 1984, followed by Brave New World. Zamyatin’s We is important but more for historical reasons, while This Perfect Day isn’t considered particularly original. But in terms of how well the story is told — in approximation, how much I enjoyed reading them — the order exactly mirrors the chronological order above: my favorite is the suspenseful This Perfect Day, and the one I most struggled to get over with was We, which is interesting in a way but written in a very confusing style, with implausible worldbuilding. It’s been a while since I read 1984, and my recent reread of Brave New World was a graphic novel adaptation so it’s hard to comment on the style of the novel, but from what I remember 1984 was the more readable of the two. It tells the gripping tale of someone who wants to rebel, whereas Huxley’s book, though definitely a masterpiece, seems closer to a dissertation on his imagined future world, using characters as props when needed. We care more about Winston Smith than Bernard Marx and John the Savage.

I told you this was cherry-picked and subjective; anyone is free to disagree with my rankings, even myself two weeks from now. Besides, add a novel or two to the list and my reasoning may look just plain silly. I decided against reading Fahrenheit 451 before writing this, just in case it destroyed my beautiful argument. Then I realized that my argument was already not very sound due to the existence of a later 20th century dystopian classic, The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) by Margaret Atwood, one of the most awfully told novels I’ve ever read, though its worldbuilding is intriguing (and horrifying) and explains, I suppose, its popularity. I’d rank it second-last, just above We.

Yet, despite all these caveats, I think there’s some truth to the idea that there’s been progress within the bounds of this specific genre (dystopia) and medium (novels). It seems certain that later authors were influenced in almost all cases by their predecessors (Huxley’s denial notwithstanding); so it makes sense that each of them would be in a position to improve upon what came before, in terms of storytelling techniques if not in terms of plot or ideas.

Or, perhaps more accurately, after the genre was born thanks to We and Brave New World, both of which get a pass on storytelling efficacy because they were original, many later authors tried their hand at dystopia; those that we still read are those who wrote the best stories. Progress in storytelling would then be culturally evolved through a process of selection, which happens to be the most reliable way to generate progress.

Today, decades after any of these novels were published, I would expect the best dystopian stories to be even better at the technicalities of storytelling: pacing, scene construction, worldbuilding exposition, and so on. This is because the genre is mature and diverse. Of course it doesn’t mean that current dystopian novels are necessarily “greater” overall; the originality of ideas counts for a lot, and if you write in a specific genre, it’s extremely hard to beat its classics in the eyes of critics — even if you may be more technically proficient. But it seems right to say that our civilization is more competent at dystopian novels today than it was in 1920, when Zamyatin was writing and the Russian Civil War, around him, was raging.

Let’s generalize. Across all genres and media, has humanity improved at the art of telling stories?

I suppose we need a working definition of “improvement,” though my guess is that an intuitive understanding will do just fine. A story is better told if it captivates its audience’s interest. If it actually conveys what it aims to convey (which is hard to do if you don’t captivate your audience’s interest). In other words, if the median1 storyteller in 2024 is better at captivating 2024 audiences than the median storyteller in 1960 or 1750 or 500 BC was at captivating a 1960 or 1750 or 500 BC audience, then there has been progress.

How could we tell? Here lies the heart of the question. Confounding factors abound, making the study of progress in storytelling (or in the arts more generally) a difficult measurement problem.

First, there’s the notion of cultural distance across time. This is why I wrote that sentence above on audiences from various dates across history. You and I, who live in the 2020s, could read a bunch of books from the 2020s and a bunch of comparable books from the 1750s, and determine which set seems better. But the books from the 2020s would have an unfair advantage: they were written with a current audience in mind. The people from 1750 were different — “the past is a different country” — and it’s theoretically possible that the books from that time, though foreign to us, were as good or even better in terms of storytelling to the people from that time than the books we have are to us. Unfortunately, we can’t exactly ask them.

There’s also cultural distance across space, i.e. between countries, language blocs, or other types of cultures. Perhaps Korean storytellers are better or worse at telling stories to Koreans than Turkish storytellers are to Turks. If you’re either Korean or Turkish, though, it’ll be hard to be unbiased. A straightforward way to avoid this confounder is to keep the analysis confined to a single country, but at sufficiently large time scales, that isn’t possible, since countries and languages appear and disappear. You can’t compare 21st century American short stories to 11th century American short stories.

Making matters more complicated is the existence of technological change. New methods to tell stories obviously appear all the time: video games, television, film, radio, periodicals, printed books, even writing itself, even language itself. We could just declare that this is what storytelling progress means and call it a day. But obviously I’m interested in a more focused version of the question, which is why I opened the essay with the narrow example of dystopian novels. I’m interested in storytelling innovations that are independent of big, broad changes in available media. But what exactly is the difference? What counts as a technology, and what doesn’t? Is a genre a technology? What about a storytelling technique like the unreliable narrator or the use of dialogue? Sure, we can dodge these questions by restricting our analysis to a single genre and media, in addition to a single culture and time period. At some point, though, we want to be able to compare across very different parts of the storytelling landscape, too.

Another major confounder, of course, is selection bias. I know people who only read old books — only the ones that have passed the test of time is worthy of theirs. This is fine as a reading strategy, but not as a way to analyze trends over time, for fairly obvious reasons. If you take a well-loved classic and measure it against some random current book, you’re likely to conclude that people wrote far better in the past. For a fairer comparison, you’d have to pick a random book from the past instead, probably one that no one ever reads anymore. Or you could compare an old classic to a book that is widely praised today, but there’s a pitfall here: it’s not easy to predict which books will stand the test of time. Some popular books are quickly forgotten.

And that’s all assuming that we can read the stories from the past. Survivorship bias suggests that the past stories we have access to aren’t necessarily representative of their time. They maybe have been passed down by successive generations because they were deemed particularly worthy, for example. We would expect that the vast majority of stories were never recorded, or having been recorded, were destroyed before reaching us, limiting what we can truly say about the past.2

Even assuming we have found ways to deal with all of these biases, progress may be difficult to detect because it might not be straightforwardly linear. Maybe some periods are much more culturally productive than others. Maybe some have, by chance, a higher concentration of genius. Maybe some were stuck for years in fashions that seem dumb today. Going from a high point to a low one may seem like the opposite of progress, yet be a part, when you zoom out, of an upward (if zigzagging) trajectory.

And lastly, I suppose I should mention subjectivity? We just don’t have an objective way of measuring how much a story “captivates its audience’s interest.” We can look at things like book sales or movie box office rankings, but they’re crude metrics, especially across different periods, and anyway many would disagree that they’re good indicators of quality. So even if we took care of the half-dozen confounders above, we’d be left with little more than vibes as a tool to actually measure anything.

With such a cornucopia of confounding factors, it’s no wonder that almost nobody ever seriously discusses the idea of progress in storytelling. It seems even hubristic to think we could ever answer the question, especially in the positive. “Look at how much better we are at storytelling than they were in the time of Homer or Shakespeare or Tolstoy!”

But what was going to be a balanced, nuanced article ended up putting me, as I was writing it, squarely in the camp of “Yes, obviously there’s been tremendous progress in storytelling, and it’s ridiculous to think otherwise.”

Let’s carry out a thought experiment. Suppose you invented time travel and brought a random person from some unspecified past period to the present, made sure they could understand your language, and then showed them some of our stories. How would they react?

They’d probably start by being extremely confused and overwhelmed, not to mention disgusted by our depraved morals, and they’d hate you for bringing them here. After they had calmed down, though, they might recognize that there are lots of techniques we use in stories that they could never witness in their own time. Interactive storytelling in video games (and gamebooks!). Various literary techniques, like unreliable narrators and stream of consciousness.3 Whatever editing methods make it more engaging to watch a recent movie than one from the 1970s. The existence of writing concepts like “chapters” or “punctuation.”

The traveller from the past would probably still hate most of our stories. But they’d be able to see that we have a richer repertoire of techniques, styles, genres, themes, etc. that we can draw from to create whatever we want. That’s probably much of what progress means, in the arts as in technology: expanding the repertoire of what we can do.4

To put it differently, we can choose to write an epic in the style of Homer if we want. But Homer couldn’t write a modern novel or a screenplay or a choose-your-own-adventure book.

None of this is to suggest that innovating in storytelling is easy. Just like innovating in tech, it’s quite hard. Most who attempt it fail (especially naïve 17-year-old kids who decide to write a Groundbreaking Novel Like Nothing Ever Seen Before5). So innovation rarely happens in an obvious way, due to all the confounders, which is why it’s not easy to find clear examples.

But it does happen. Tons of people tell stories, every day, and sometimes, some of them, by chance and skill, manage to arrange information in an slightly better way than before. A joke becomes a tiny bit funnier due to an altered twist of phrase, and then that version spreads. A filmmaker builds uses lighting and camera lenses in a manner that nobody had thought of before, and suddenly there’s a new film genre in town. A new word is coined to refer to a complicated concept we had no handle for, and from now on the vocabulary of your language is forever expanded; a new note that you can hit, as necessary, to tell the stories you have to tell.

I chose “median” over “best” to allow for the possibility of genius storytellers breaking the trend, though I doubt it actually makes a difference. I suppose it is possible that progress looks different at the top, middle, and bottom parts of the story quality spectrum.

Also, records may be altered. For example, we can’t really use oral history at all for comparisons, since it’s highly likely that later storytellers made various tweaks to their tales compared to their predecessors, even if they consider that they were being faithful. But even written stories aren’t immune from random mutations, especially before the invention of the printing press, when they had to be copied by hand.

This Quora answer has a bunch of good examples from the 20th century.

We can make parallels in other arts. In music, new ways of playing an instrument, and new compositional techniques, and new instrument themselves constantly appear. In figure skating, new, more impressive jumps get developed over time; watching old videos tends to look very underwhelming today. In the visual arts, material advances (like pigments etc.) are an obvious way the field progresses; another totally different kind of innovations might be the emergence of abstract art.

i.e. me a long time ago

TL;DR: No, storytelling has not improved over time (since ~8000 ya). What *has* gotten worse are our attention spans, imaginations, and sensitivities—strip all of embodied reality down to 2.1 sensory channels, flip the input context every ~15 seconds, and leave absolutely nothing ambiguous, and you have our current “storytelling” culture creating generations of “consumers” rather than citizens of culture.

This was an interesting read! I think there’s a lot of nuance to this question. Perhaps it’s worth also considering what different audiences need from different stories over time? I’ve definitely noticed a trend in my own readers, since the pandemic, wanting stories with hopeful endings and positive messages, as if their emotional needs have changed to require more comfort and reassurance. I think writers have adapted to that. Perhaps a more emotionally resilient future society would look at our current storytelling and think it quaint or whimsical, but it’s what readers need right now, and writers today are better equipped than ever to understand, and respond to, the needs of their contemporary audience. Anyway, I enjoyed the essay.