I recently re-read a classic 20th century dystopian novel, This Perfect Day by Ira Levin (1970). It’s similar in many ways to Brave New World by Aldous Huxley (1932): the world is unified under a single state and ideology, optimized by technology (the assembly line in BNW, a supercomputer in TPD) and maintained by drugs and social conformity, with the result of making everyone seemingly happy; the only exceptions are occasional deviants who go on to live on a few islands outside of the system. This Perfect Day has less literary significance and originality than Brave New World, but it makes up for it by being a gripping read.

The central question of books like these is: Why is the dystopia bad? Everyone is kept happy; there is no disease or conflict or poverty; there are still aspirational achievements, like colonies across the solar system in This Perfect Day. This is in sharp contrast with the other big subgenre of dystopia, exemplified by George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, where the badness is obvious — they’re full of fear, surveillance, violence and deprivation. In BNW and TPD, there is no need for any of that. The drugs and conditioning make almost everyone satisfied and peaceful. Why is that happiness unbearable?1

Many answers have been proposed. Often they revolve around liberty. This Perfect Day itself explicitly discusses the importance of freedom and the dichotomy between freedom from (disease, conflict, poverty) and freedom to (do whatever you want). Dystopias, and for that matter many utopias, are intuitively bad because they preordain the world, dissolving human agency.

But another class of answer revolves around one of my dearest themes here on the blog: simplicity vs. complexity. Dystopias are distasteful because they are, almost always, unbearably simple.

This Perfect Day takes the simplification of the world to an impressive degree. Under the leadership of its single central computer under the Alps, UniComp, society is fascinatingly uniform. Eugenics has merged all the races into a single “Family,” all of its members the same height, the same skin color, the same traits; the people who, for whatever reason, deviate a bit from the norm tend to view it as a source of shame. The differences between the genders have been erased: women don’t grow breasts, men don’t grow beards. Our diversity of personal names has been simplified into a set of exactly eight appellations: Jesus, Karl, Bob, and Li for men, and Mary, Anna, Peace, and Yin for women (alphanumeric codes like KD37T5002 complete those names for when individual identification is needed). There is only one language, presumably English. The old cities all over each continent have been destroyed and rebuilt with about three models of “blank white concrete slabs” as structures for people to work and live in2 — and the cities now bear alphanumeric names like EUR55128 and RUS41500 and ARG20400. In all of those cities, the food consists of the same three items: totalcakes, cokes, and tea. (Partly through the book a “pleasant second flavor” of totalcake is introduced.) Time is strictly managed: there is mandatory TV in the evenings, Saturday night is for sex, Sunday is a day off, and the rest is for whatever work UniComp decided you would devote your life to.

This is great worldbuilding. The world of This Perfect Day is believable, coherent, intriguing. It’s not perfect — no fictional worldbuilding ever is — but the illusion works. It works because imagining a uniform world, with a single culture and language, and very little variety in human behavior, and no inter-organization dynamics because there is just one world government, is much more doable than the opposite: imagining a world with a myriad cultures and subcultures, billions of free-thinking humans, and thousands of governments and organizations competing and collaborating with each other.

So it’s great worldbuilding, but it’s also kind of cheap. It’s cheating, in a sense. Totally justifiable cheating, because it gets us cool stories and fun explorations of hypothetical worlds, but cheating nonetheless, the way that TV series are frequently set in summer not because their creators particularly want to, or because it would be particularly realistic, but just because it is inconvenient to shoot them in winter. Likewise, the simplicity of dystopia is often a matter of practicality.

It’s a happy accident, for writers of dystopia, that such a practical concern happens to generate the horror that makes their stories interesting. (It’s also an unhappy accident for would-be writers of utopias, since their necessarily simplistic worldbuilding will always tend to generate more horror than fondness. That’s probably why writing dystopias is way easier.)

But why exactly does civilizational simplicity evoke horror? The answer may have to do with the aforementioned point on freedom: whenever a human exercises his or her agency, he or she tends to make the world more complicated. For the simplicity to be maintained, agency has to be restricted, as it so clearly is in This Perfect Day, and this makes us uncomfortable.

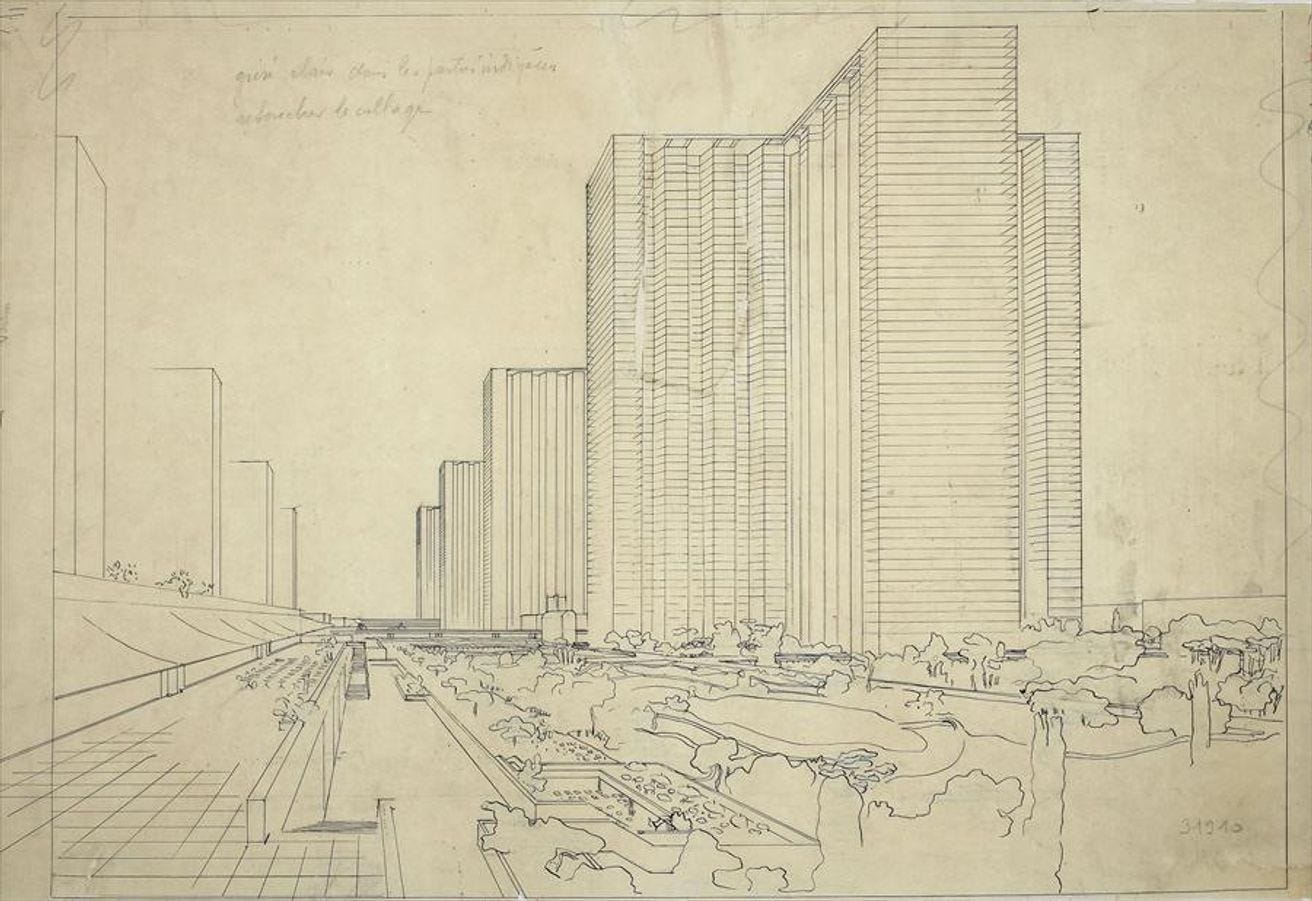

More generally, excess simplicity tends to be boring, uninteresting. Ugly, even, though here I want to be careful: things are ugly for a reason, and in this case the reason is uninterestingness. Large featureless buildings, “blank white concrete slabs,” are generally disliked; everyone recognizes that it would have been a disaster if Le Corbusier’s idea to replace half of Paris with the Plan Voisin had been implemented. Similarly, it would be tragically boring if everyone you knew had the same opinions and the same tastes, or if you could only ever eat the same one meal.

This is a fundamental point of human nature, I think, and one that I’ve expressed in half a dozen different ways on this blog over the years: uniformity is undesirable because we know, on some level, that it doesn’t work. Any supposedly optimal society we imagine or build will never actually be optimal, because reality is too complicated, and the only way to improve it is by having a variety of people and ideas going around. And we know this thanks to evolution, which has ingrained the desire for variety very deeply in us, by making us able to feel boredom and beauty. Perhaps that happened because evolution itself depends on it; it wouldn’t occur if there weren’t occasional “deviant” mutations in the DNA.

A delicious irony in This Perfect Day is that the designers of UniComp actually recognize this point. There’s a whole complicated setup that allows a tiny number of deviant people to become elite and use their intellect and creativity to improve the system. Yet they fail to realize that the world would be better if they allowed far more deviancy than that. And so their world is stuck in a local optimum, one that seems good on some measures — no disease! no conflict! no poverty! colonies on Mars and Venus and Titan! — but feels downright horrifying to the protagonist, and to us.

Fortunately, such a scenario is unlikely to ever happen. All fictional dystopias are unlikely to happen, just as utopias also are. The world is too complex; and we humans need variety to too large a degree to let our civilization turn itself into a simplistic affair, governed by a single state like in Brave New World, or a handful like in 1984, or a supercomputer like in This Perfect Day, and kept in stasis by constantly suppressing human potential through drugs or mutual surveillance. None of that is ever going to happen. Right?

The first time I read This Perfect Day was in high school, in a French translation. Its French title is Un bonheur insoutenable, which translates to “Unbearable Happiness”.

The buildings are also described as having no windows. For some reason this was the detail that felt unbelievable to me, and I chose to imagine the buildings as having windows anyway. Surely even the most horribly dystopian supercomputer-dictator wouldn’t be so cruel as to deprive us of looking outside?

All utopias are dystopias. Any society simple enough to be engineered is too simple to embrace humanity.

Interesting! I aspire to write about a multiversity of challenged utopian projects. My inspiration comes from Judith Butler's undoing gender. Her suggestion is the opposite of simplicity. She says something like the task of all these movements is to cease legislating the lives of others to quit prescribing for all what is livable only for some. And the goal is a livable existence for all. When I include the land and all beings, even more complexity comes in. I think that what makes this kind of sci-fi dystopia simplicity horrible, especially with this contained production of deviance, is partly what we can imagine we would experience with an AI ruler. As you say, it has to do with what we mean by humanity (and nature) which is messy and chaotic and flawed and ingenious. Perfectionism is also hell.